Biden Administration’s Healthcare Future is One of Promise & Peril

Last month, the Biden Administration issued a press release outlining a look toward the future of American health care policy. Priorities in the presser include ever elusive efforts around prescription drug pricing and items with steep price tags like expanding Medicare coverage to include dental, hearing, and vision benefits, a federal Medicaid look-alike program to fill the coverage gaps in non-expansion states, and extending Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies enhancements instituted under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in March. Many of these efforts are tied to the upcoming $3.5 trillion reconciliation package.

President Biden renewed his call in support of the Democrats effort to negotiate Medicare prescription drug costs, enshrined in H.R. 3. Drug pricing reform has been an exceptional challenge despite relatively popular support among the voting public, in particular among seniors. The pharmseutical industry has long touted drug prices set by manufacturers do not represent the largest barriers to care and mandating lower drug costs would harm innovation and development of new products. Indeed, for most Americans, some form of insurance payer, public or private, is the arbiter of end-user costs by way of cost-sharing (co-pays and co-insurance payments). To even get to that point, consumers need to be able to afford monthly premiums which can range from no-cost to the enrollee to hundreds of dollars for those without access to Medicaid or federal subsidies. The argument from the drug-making industry giants is for Congress to focus efforts that more directly impact consumers’ own costs, not health care industry’s costs. Pharmaceutical manufacturers further argue mandated price negotiation proposals would harm the industry’s ability to invest the development of new products. To this end, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released a report giving some credence to this claim. The CBO’s report found immediate drug development would hardly be impacted as those medications currently “in the pipeline” would largely be safe, but a near 10% reduction in new drugs over the next 30 years. While new drug development has largely been focused on “personalized” medicine – or more specific treatments for things like cancer – implementing mRNA technology into vaccines is indeed a matter of innovation (having moved from theoretical to shots-in-arms less than a year ago). With a pandemic still bearing down on the globe, linking the need between development and combating future public health threats should be anticipated.

The administration’s effort to leverage Medicare isn’t limited to drug pricing. Another tectonic plate-sized move would seek to expand “basic” Medicare to include dental, hearing, and vision coverage. Congressional Democrats, while generally open to the idea, are already struggling with timing of such an expansion, angering Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) by suggesting a delay until 2028. While any patient with any ailments related to their oral health, hearing, and vision will readily tell you these are critical and necessary coverages, even some of the most common of needs, the private health care insurance industry generally requires adult consumers to get these benefits as add-ons and the annual benefit cap is dangerously low (with dental coverage rarely offering more than $500 in benefit and vision coverage capping at one set of frames, both with networks so narrow as to be near meaningless for patients with transportation challenges). While the ACA expanded a mandatory coverage for children to include dental and vision benefits in-line with private adult coverage caps, the legislation did nothing to mandate similar coverages for adults and did not require private payers to make access to these types of care more meaningful (expanded networks and larger program benefits to more accurately match costs of respective care).

The other two massive proposals the Biden Administration is seeking support for, more directly impact American health care consumers than any other effort from the administration: maintaining expanded marketplace subsidies and a federal look-a-like for people living in the 12 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion provisions. The administration has decent data to back this idea, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report showing a drop in the uninsured rate from 2019 to 2020 by 1.9 million people, largely attributed by pandemic-oriented programs requiring states to maintain their Medicaid rolls. The administration and Congressional Democrats are expected to argue subsequently passed legislation allowing for expanded subsidies and maintained Medicaid rolls improved access to and affordability of care for vulnerable Americans during the pandemic. As the nation rides through another surge of illness, hospitalizations, and death from the same pandemic “now isn’t the time to stop”, or some argument along those lines, will likely be the rhetoric driving these initiatives.

Speaking of the pandemic, President Biden outlined his administration’s next steps in combating COVID-19 on Thursday, September 9th. The six-pronged approach, entitled “Path out of the Pandemic”, includes leveraging funding to support mitigation measures in schools (including back-filling salaries for those affected by anti-mask mandates and improving urging the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] to authorize vaccines for children under the age of 12), directing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to issue a rule mandating vaccines or routinized testing for employers with more than 100 employees (affecting about 80 million employees) and mandating federally funded health care provider entities to require vaccination of all staff, pushing for booster shots despite the World Health Organization’s call for a moratorium until greater global equity in access can be attained, supporting small businesses through previously used loan schemes, and an effort to expand qualified health care personnel to distribute COVID-19 related care amid a surge threatening the nation’s hospitals ability to provide even basic care. Notably missing from this proposal are infrastructure supports for schools to improve ventilation, individual financial support (extension of pandemic unemployment programs or another round of direct stimulus payments), longer-term disability systems to support “long-COVID” patients and any yet-unknown post-viral syndromes, and housing support – which is desperately needed as the administration’s eviction moratorium has fallen victim to ideological legal fights, states having been slow to distribute rental assistance funds, and landlords are reportedly refusing rental assistance dollars in favor of eviction. While the plan outlines specific “economic recovery”, a great deal is left to be desired to ensure families and individuals succeed in the ongoing pandemic. Focusing on business success has thus far proven a limited benefit to families and more needs to be done to directly benefit patients and families navigating an uncertain future.

President Biden did not address global vaccine equity in his speech, later saying a plan would come “later”. The problem, of course, is in a viral pandemic, variant development has furthered risks to wealthy countries with robust vaccine access and threatened the economic future of the globe.

To top off all of this policy-making news, Judge Reed O’Connor is taking another swing at dismantling some of the most popular provisions of the ACA. Well, rather, yet another plaintiff has come to the sympathetic judge’s court in an effort to gut the legislation’s preventative care provisions by both “morality” and “process” arguments in Kelley v. Becerra. The suit takes exception to a requirement that insurers must cover particular preventative care as prescribed by three entities within the government (the Health Resources Services Administration – HRSA, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – ACIP, and the Preventative Services Takes Force – PSTF), which require coverage of contraceptives and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with no-cost sharing to the patient, among a myriad of other things – including certain vaccine coverage. By now, between O’Connor’s rabid disregard for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans and obsessive effort to dismantle the ACA at every chance he can – both to his own humiliation after the Supreme Court finally go their hands on his rulings – Reed O’Connor may finally have his moment to claim a victory – I mean – the plaintiffs in Kelley may well succeed due to the Supreme Court’s most recent makeover.

As elected officials are gearing up for their midterm campaigns, how these next few months play out will be pretty critical in setting the frame for public policy “successes” and “failures”. Journalists would do well to tap into the expertise of patient advocates in contextualizing the real-world application of these policies, both during and after budget-making lights the path to our future – for better or worse.

Amid HIV Outbreaks, Covid-19 Fractures Existing Public Health Efforts

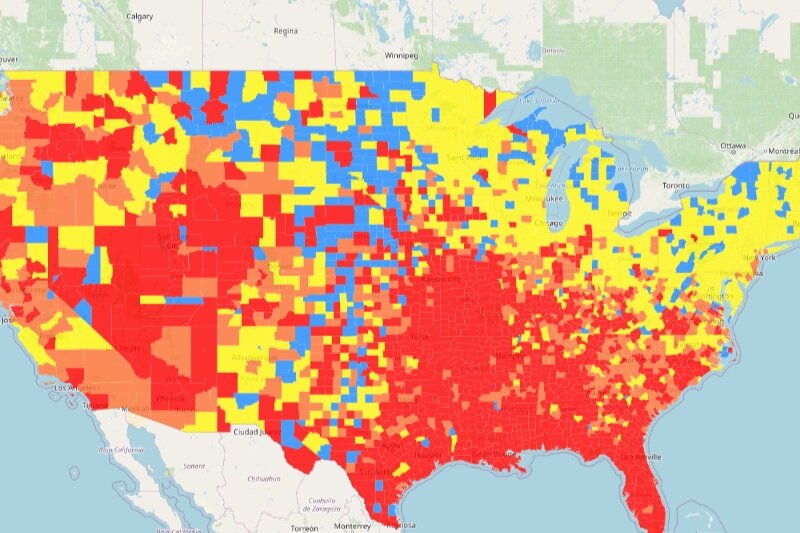

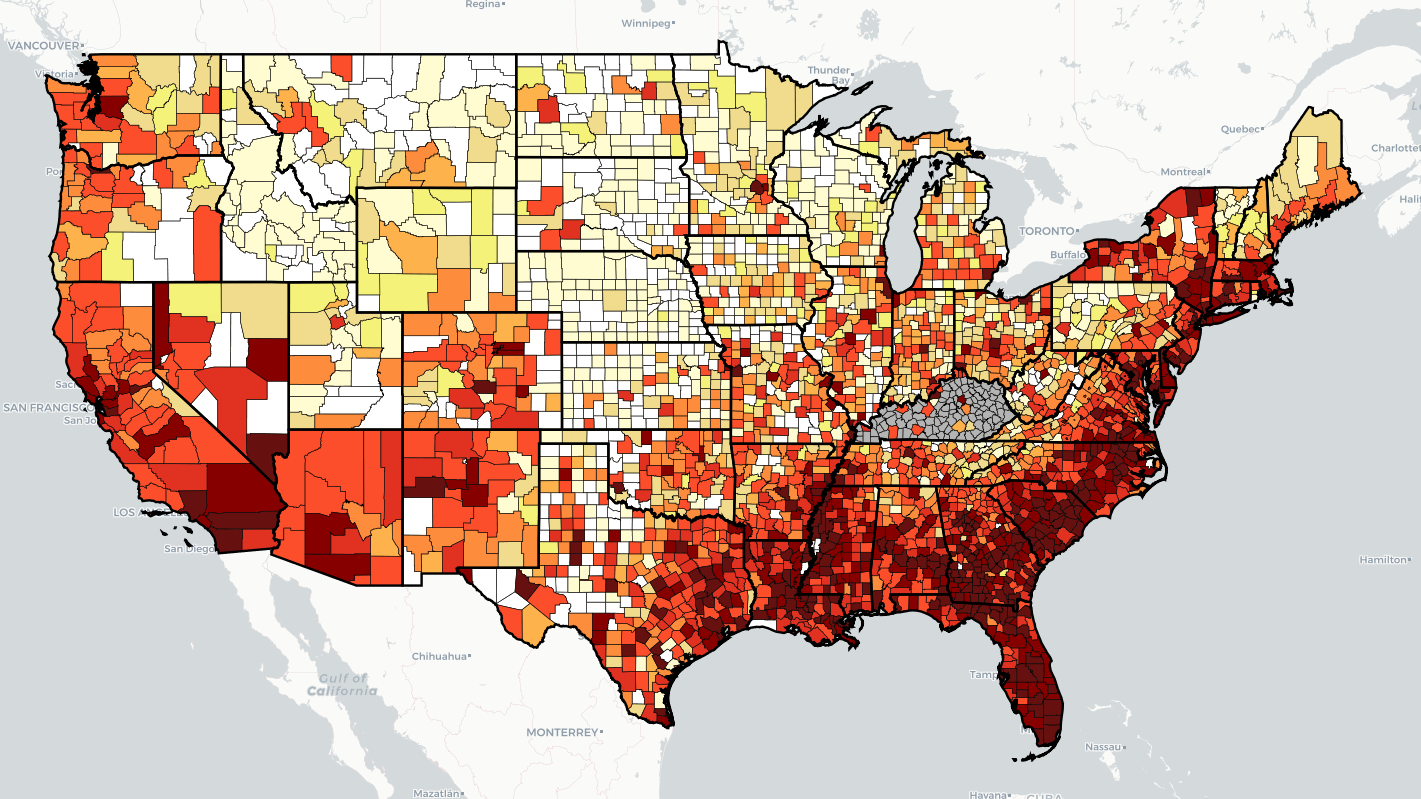

“Every health disparity map in the United States is the same,” Alex Vance, Senior Director of Advocacy and Public Policy at the International Association of Providers in AIDS Care, has repeatedly stated when discussing the COVID-19 pandemic and the very real risks of “back sliding” in our moderate advancements in the United States’ effort to End the HIV Epidemic. There’s no better way to demonstrate this than by showing you.

As another “wave” of Covid-19 ravages the country, increasing cases, hospitalization rates, and eventually deaths, existing public health needs around HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections continue to be strained, pushed to the back burner and most often in geographic areas where we need to be able to juggle more, not less; particularly across the South. Unlike Covid-19 outbreaks, which receive fairly immediate attention in terms of reporting and response, HIV outbreaks can and do often take a year or more to notice and begin action to address. While there’s concern about juggling the demands of addressing concurrent pandemics, some (certainly not all) of this reporting and response is beginning to speed up with regard to HIV.

West Virginia’s Kanawha County HIV outbreak is considered a 2020 outbreak, though just recently received a report from the Center’s for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) on next steps and recommendations to address. Despite these recommendations including supporting syringe exchange programs and community-based services, local officials continue a politically oriented response by seeking to limit the support of syringe exchange programs, threatening their ability to operate and aid in addressing the needs of the local community. Another outbreak in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula was identified in July of this year, with rural Kalkaska County reporting a higher rate of new HIV diagnoses than even Detroit. Kalkaska County is so similarly situated to Scott County, Indiana, it’s striking. Louisville, Kentucky has reported almost as many new HIV diagnoses in the first half of 2021 as the area does annually. And Duluth, outside of Saint Louis, Minnesota, joined neighboring Hennepin and Ramsey Counties with declared outbreaks tied to 2019 and 2018, respectively.

What’s important to note about 2020’s marked reduction in HIV screenings is not just the delay in newly diagnosing people living with HIV, but the lack of ability to link people to care upon diagnosis, beginning antiretroviral therapy and taking steps to reduce the person’s viral load. With at-home testing being the substitute offering, linkage to care and counseling for people self-testing may be hampered according to some concerned advocates. Achieving viral suppression also reduces the possibility of transmitting HIV by way of sexual contact to zero (“Undetectable = Untransmittable”) – creating a process where people living with HIV are not just a patient group needing identification, but play a critical role in preventing new transmissions.

In reviewing the possibilities of delayed care and delayed screening, public health officials and advocates should remember a new diagnosis is not necessarily indicative of a new transmission. A potential problem in and of itself, in assessing Covid-19 disruptions in screening and care, is the possibility of a “bottle neck” of new testing revealing new HIV diagnoses which otherwise might have been identified in the previous year if not for stay-at-home orders, education and public awareness campaigns, and community health care providers having had to take a step or shift gears entirely from HIV to Covid-19. It will take years for us to truly understand the breadth and reach of Covid-19 on the world’s only concurrent pandemic, even in the “most advanced country in the world”.

What can already be well-appreciated and should be well-understood is we cannot afford to keep asking community-based health care providers and community partners in combatting the domestic HIV epidemic to keep sacrificing HIV screening and linkage to care in order to address Covid-19. What must be prioritized is funding, programming, training, and most importantly hiring of new talent in addition to existing programs in order to address both sets of needs.

As I summarized in a previous blog, capacity has been breached, we cannot afford to keep asking public health to do more with less and expect to succeed in addressing Covid-19, HIV, viral hepatitis, STIs, or the opioid epidemic.

SCOTUS Sets Dangerous Precedent for Incarcerated People Needing Care

The 8th Amendment to the United States Constitution reads as follows:

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”

Long standing precedent, Estelle v. Gamble, sets one standard of “cruel and unusual punishment” as “deliberate indifference” to the medical needs of incarcerated people. Additional precedents include an affirmative need to evaluate these medical needs on an individual basis, cannot be excused as mere neglect when an incarcerated person is at “substantial risk of harm” if that need is not met, and that providing care that is “grossly inadequate as well as by a decision to take an easier but less efficacious course of treatment” are also considered measures of “deliberate indifference”.

In August 2020, the US Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit added an asterisk: “…if the state decides it can afford to…” provide the care required under the 8th amendment [paraphrasing].

Last month, the Supreme Court of the United States refused to hear the appeal of Atkins v. Parker, where a group of incarcerated people alleged their 8th amendment rights were violated because the state was rationing their HCV related care. In the 6th Circuit appeal, the state argued, successfully, that rationing care was “reasonable” due to budgetary constraints supposedly outside the control of the prison system.

Coverage of both appeals referred to a 2018 settlement in Michigan, wherein the state’s Medicaid program, after suit, expanded coverage to include direct acting agents. However, in a lone descent, Judge Gilman drew more direct parallels in other SCOTUS and 11th Circuit rulings regarding prison overcrowding and access to AZT (case was in 1991) for incarcerated people, ruling in part “The fast moving status of research and medical advances in AIDS treatment is continually redefining what constitutes reasonable treatment.”, respectively. Indeed, in Atkins, the state’s position boils down to “new drugs are too expensive” to be “reasonable” for incarcerated people to have access to. The majority argued because Tennessee’s Department of Corrections Medical Director, Dr. Williams, had only recently restructured the state’s rationing of DAAs and individual assessments, the state had fulfilled its obligations, within budgetary constraints. Judge Gilman correctly argued the state’s medical administrator for the prisons was obligated to request appropriate funding to meet these needs in order to fulfill the state’s 8th amendment requirements – of which, no evidence was presented to prove Dr. Williams did make such a request. Judge Gilman closes the descent with well-established citation that treating HCV early reduces overall costs of care compared to delayed or denied care.

That said, with SCOTUS refusing to hear the appeal, affected people in prisons are facing a dangerous precedent of state officials shirking their Constitutional responsibilities to provide a basic standard of care to the people in their custody. Legislatures merely need to neglect increasing a budget, as we’ve seen in other state-run health care programs, in order to avoid meeting their Constitutional duties.

Interestingly, also in April, the Department of Justice filed a statement of interest in a case in the Georgia, where an incarcerated transgender woman has been subject to violent attacks and refusal of care. The Biden administration’s position here is denying incarcerated people gender affirming medical care is a violation of the 8th amendment’s protections and is thus “deliberate indifference” to the person’s medical needs.

There’s an intersection between Diamond and Atkins that cannot be missed. While the timing of Atkins didn’t favor intervention by the current administration, this administration must also recognize the precedent set forth by Atkins, fight for appropriate funding measures to meet the medical needs of incarcerated people, and update Federal Bureau of Prisons HCV guidance to with regard to prioritization not justifying rationing of care. As with nearly every infectious disease, prisons are both a “canary in the coal mine” of the local community and the ideal environment for manifesting new diagnoses.

The most startling statistic in Atkins is even after DAAs were available, at least 109 incarcerated people had died due to HCV complications. Death by neglect, by rationing is still a death sentence.

Even as I write this, President Biden argued “health care should be a right, not a privilege.”

As it turns out, according to the 6th Circuit, it’s a right, with a large asterisk.

To ensure this injustice is answered for, advocates must remember the courts do not always find justice and our advocacy must reach every level of government. If we don’t, the asterisks will continue to add up.

The Most Meaningful Public Health Intervention: Housing

A note on the language used in this article: Some housing advocates reference a difference between “homelessness” and “houselessness” with exceptional, nuanced conversations on individual experiences with housing instability, connection to community, and personal autonomy. While some advocates may opt to consider a frame of “home is where the heart is” as an issue of empowerment, I, as an author and advocate, use these distinctions because of well-established links between housing instability and uncertainty in situations of domestic violence. A roof does not necessarily a “home” make. For the stakeholder targets of this blog, the link between intimate partner violence/domestic violence and HIV is so notable, the Department of Housing and Urban Development has recently announced funding opportunities for joint demonstration projects between HOPWA and VAWA (Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS and the Violence Against Women Act, respectively).

For 30 years, people living with HIV have advocated “housing is health (care)” religiously. A drumbeat of nearly every action, the inevitable topic of any roundtable or meeting, even if housing isn’t an agenda item – or especially if housing isn’t an agenda item. Arguably, when it comes to issues of “social” Justice and policies impacting the notion of equity, outpacing even health care is housing. Housing is the lone sustainable investment any person or family in the United States can make and, generally, expect to last well beyond their own time. Housing is the basis of both defeating and maintaining systems of inequity and oppression. Housing is such a significant factor in individual and collective outcomes it had its own carve out, separate and apart from the Ryan White Care Act, via the program known as Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS.

Indeed, the housing’s impact on health care is so exceptional, in 2019, the American Medical Association built upon limited calls to improve identification access for people experiencing houselessness and expanded their policy position for more comprehensive and collaborative resources aimed to bring care to this population and called for decriminalizing houselessness. In the same year, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual “point in time” data estimated about 568,000 people were experiencing houselessness on any given night in the United States, a near 10% increase of “unsheltered persons” from the prior year.

Late last month, the University of Bristol published in The Lancet a systemic review and meta-analysis of housing instability and houselessness finding among people who inject drugs (PWID), recent houselessness and housing instability were associated with a 55% and 65% increase in HIV and HCV acquisition, respectively. Additional findings include of the global 15.6 million PWID, over 1 in 6 have acquired HIV and over half have acquired HCV at some point and an astounding estimation that half of PWID in North America actively experiencing houselessness or housing instability.

None of the studies included data collect prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. While several states near immediately began introducing short-term eviction moratoriums and the CARES Act provided for federally backed mortgage holders to seek forbearance or deferment, these protections were short-lived, with many states looking toward the federal government for guidance. As with many issues, the summer of 2020 brought the country little comfort due to a lack of cohesive and coordinated public health response to the emergency. A paper published by housing heavy-weight, Emily Benfer, and HIV champion, Gregg Gonsalves, among others, found this failure to uphold and maintain meaningful and enforceable state-based eviction moratoriums contributed to racial health inequity and cited research finding that lifting moratoriums prematurely, triggering displacement, is associated with an additional 10,700 preventable COVID-19 deaths and 433,700 excess cases. In fact, an organization Benfer serves with, Eviction Lab, rates nearly every state in the country as “one star” in terms of housing protections for renters.

Under this frame, tens of millions of people in the United States are at extraordinary risk of contracting COVID-19. Which is part of why the Centers of Disease Control attempted to flex some public health muscle by issuing an eviction moratorium for public health purposes in October, 2020. Like with other investments made in the fight against COVID, the move was bittersweet for public health advocates at the intersection of housing and HIV, HCV, and SUD syndemics – where was this before now?

“Among the Biden administration’s first priorities is the advancement of racial equity and support for underserved communities,” Benfer said. “This requires redress of the structural and systemic discrimination in housing. As an immediate measure, the federal government should bolster the nationwide moratorium on evictions to apply to all stages of eviction, all forms of eviction, and all renters who face housing instability. At the same time, to prevent an avalanche of evictions and protect small property owners from harm once moratoria lapse, policy makers must provide the rental assistance necessary to address the accumulating back rent and sustain renters, state and local governments, and the housing market—and direct it to the communities at the greatest risk of housing instability.”

“Preventing COVID-19 eviction alone could save the U.S. upwards of $129 billion in social and health care costs associated with homelessness,” Benfer added.

However, the CDC’s moratorium is on shaky ground and implementation/access is not automatic – those seeking to use this protection most pro-actively notify their landlords and express intent to seek cover of the moratorium in eviction court. Several states and localities have not evenly implemented the moratorium or setting up “eviction kiosks” to expedite the process, because so many cases were in que, and some going so far as to list children as defendants in eviction actions. Which, according to Benfer, is not an uncommon occurrence. And due to the lack of protections for tenants and outdated credit reporting associated with eviction judgements, these legal actions can and often do follow people for at least a decade, compounding barriers to housing and drastically increasing the risk of houselessness. Because state-based protections have ended, Texas is allowing evictions to resume and the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals has recently allowed a challenge to the authority expressed by the CDC for the moratorium to move forward, even as some landlords are openly exploiting loopholes in the moratorium.

Landlords aren’t the only abusive persons seeking to take advantage of weaknesses in our housing protections. An unfortunate side-effect of the moratorium actions and our lack of investment in ensuring adequate resources for people experiencing intimate partner violence is perpetrators exploited stay-at-home orders and survivors, who are already at exceptional risk of housing instability, with an estimated 26% increase in domestic violence abuse calls made in some cities across the US during the strictest of those orders.

Additionally, with more people facing a lack of houselessness, even more are now at risk for “mobile homelessness” – or a lack of car to sleep in – an issue which may be masking just how many people are experiencing houselessness and housing instability, due to the design of some point in time surveys are conducted. And with an estimated 49% increase in chronic homelessness expected as a result of COVID-19 over the next 4 years, the potential exacerbation of the existing housing crisis in the US may well likely become an even larger, permanent feature without extraordinary action from all levels of government and, or even especially, private stakeholders. To put this figure into context, this would twice as much homelessness as was caused by the 2008 housing recession.

In The American Eviction Crisis, Explained, Benfer suggests there’s some basic policy moves to be made for longer-term successes:

“In the long term, federal, state, and local policymakers must reform the housing market in a way that provides equal access to housing, thriving communities, and areas of opportunity. Rental subsidies, new construction or rehabilitation, home ownership, and investment in long ignored communities would increase long-term affordable housing. Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) must remedy the current market conditions that can be traced to racially discriminatory lending policies. This means GSEs must address disparities in asset accumulation and the persistence of discrimination in mortgage lending and the siting of homes.

Where eviction is absolutely necessary, the eviction system itself must be reformed. Evidence-based interventions, such as providing a right to counsel, diversion programs, ‘just cause’ and ‘clean hands’ policies, as well as altering the eviction process, and sealing or redacting identifying information from eviction records, can prevent or mitigate the harm of eviction.”

That long-term investment is well past-due in addressing the needs of people living with and affected by HIV, HCV, and substance use disorder.

Benfer added, “Eviction prevention and the right to safe and decent housing must be the priority. As President Biden said while signing executive orders directed at ending housing discrimination: ‘Housing is a right in America, and homeownership is an essential tool to wealth creation and to be passed down to generations.’ It’s time the U.S. fulfilled the promises of the 1944 Economic Bill of Rights, which includes a right to a decent home, and the 1949 Housing Act that set the national housing goal: ‘the realization as soon as feasible of the goal of a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family.’ Ultimately, our policies and budgets reflect our humanity and morality as a nation, and nothing could justify the continued denial of basic human needs and access to opportunity. If we are ever to call our society humane or just, we must finally redress housing disparities and discrimination and secure every American’s right to a safe and decent home.”

For far too long, housing as been placed on a shelf as an “unreachable” necessity in actionable advocacy. We cannot afford to “kick this can down the road” any longer. We’ve long known housing is one of the most effective interventions in prevention and in patient care. The oft-touted “it’s too expensive” excuse has manifested a broken dam with lives sifting through the cracks. We already pay for housing for PWID, it’s just most often manifested in the form of imprisonment. A far more meaningful investment in a person’s recovery and success, regardless of recovery, and in community health and in Ending the HIV Epidemic and in ending violence against women and interrupting cycles of generational poverty and answering our most sacred, moral promise and…and…and… would be to address the issue squarely: it’s time to invest in housing.

Covid-19: How Far We’ve Come & How Far We Have to Go

Unraveling a tangle of yarn can be maddening. Pull here, threads get tighter. Pull there, you’ve created another knot. Now, imagine having to weave with the same tangle – “undo” a well-organized mess and make it something functional, beautiful even. The fragile public health system in United States during the Covid-19 pandemic is much like that tangled yarn.

This dual task is very much an oversimplified explanation of where the American health care landscape exists in this moment. Like most collective traumas, this stage isn’t the “undoing” stage, it’s the stop the damage stage. In writing the first blog of the year, tracking site Worldometers reported 20 million confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United states and about 345,000 COVID-19 deaths. As of the time of this writing, the same site is reporting more than 30 million confirmed COVID-19 cases in the US and about 550,000 COVID-19 deaths. Daily case counts continue to remain high at around 50 thousand confirmed cases a day and around 1,100 deaths per day on average. While the introduction of 3 vaccine products has brought hope and another tool to our COVID toolkit, and daily new cases and deaths are far below their height, the pandemic still rages on.

Which is…concerning for the entirety of the health care spectrum and especially so for those spaces that have been historically underserved or needing additional protection or funding. From the Centers for Disease Control report at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) the United States performed at least 700,000 fewer HIV screenings and 5,000 fewer new diagnoses in the first 6 months of the pandemic (compared to the same time in 2019) to the extraordinary implications of COVID among vulnerable populations to Senators Grassley and Klobuchar introducing legislation to allow drug importation (despite very clear warnings about why this is not a great idea) to the Biden Administration issuing a formal disapproval of Medicaid work requirements, to say information is coming at “break neck speed” may well be as much of an understatement as a tangled ball of yarn.

With an emerging “surveillance gap” for both HIV and HCV, a startling HIV outbreak in West Virginia, overdoses increasing as a result of COVID, some of greatest tools gained in combating this pandemic, even those advocated for by the CDC, have already started to go away as states begin to “open up”. Indeed, Congress has already begun taking up old questions regarding telehealth restrictions and payment systems designs, this time with an eye for permanency.

While President Joseph R. Biden’s American Rescue Plan, recently passed by Congress and signed into law, offers a great deal of funding to address the needs of certain entities and programs to tackle COVID and even offers the most meaningful adjustments to the Affordable Care Act by expanding subsidies, the existing needs of the health care ecosystem have largely been neglected for the last year. Well…far longer…but I digress. Like any trauma, our need to strengthen patient protections and access, incentivize quality of care over quantity of services, and meaningfully reduce health disparities have been the ends of thread tightening around the knot of COVID. This pandemic did not create these disparities and the needs outlined above – but not having a plan for a pandemic, not addressing structural inequities and these burning policy needs with the urgency they so deserve absolutely made us more vulnerable to the most devastating impacts of any pandemic.

This isn’t “the end”, certainly. For advocates, this has always been our “normal”. We need those who have hung on our every word and insight through this emergency to stay at the table – we’re not done yet. Everything you were outraged by (and may still be enraged by thanks to vaccine access scarcity) remains and will continue to loom just over our shoulders, waiting to be exploited by an opportunistic disaster.

Indeed, the ghost of Scott County may well continue to haunt us for some time to come. This is, after all, a very big ball of very tangled yarn.

Modeling Navigation: Hepatitis C Toolkit for Improving Care for People Who Use Drugs

In September 2020, our friends at the National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors announced the launch of a new hepatitis C toolkit and navigation model to improve care for people who use drugs (PWUD) and other impacted populations. NASTAD, in partnership with the New York City Health Department, spent 8 years developing this model of care navigation and the associated toolkit and has made an informational training video available to preview the program for interested health departments, providers, and community-based organizations.

The model builds upon what’s now common knowledge: clients often need help navigating complex systems of care, an influx of information, and available support. NASTAD’s training video walks viewers (and prospective partners) through nearly every aspect of the model, from staffing needs to potential funding sources. While standard roles are as expected, including program managers and data personnel, rather than strictly relying on peers, the toolkit specifically delineates between “peer navigators” and “patient navigators”, including suggested job descriptions and distinctions on educational requirements. Notably, the peer role works to support the activities of the patient navigator role (as opposed to supporting case management work directly, as seen in many HIV peer programs). Entities considering the model should note: combining these roles may weaken the efficacy of the program and, given role descriptions, overburden staff assigned to the task. Further, for these roles to be effective, providers will need to be comfortable with an active navigator advocating for and with a client. Those same providers should also note, both navigators are designed to support positive health outcomes for clients and to work in tandem with a client’s provider, including medication adherence support, follow up with provider instructions, and to ensure appointments are attended.

NASTAD’s model envisions a comprehensive approach of assessment beginning at the time of contact (either during outreach or testing activities) and throughout the care continuum. From education to treatment preparedness, the model’s training curriculum and suggested documents prompt both types of navigators to consider their language, a client’s needs in housing, stress management, co-occurring health issues, and encourage actively linking clients to resources that are not necessarily medically based. The model supports this approach from the very design of the program – highlighting the success of (and need for) syringe services programs (SSPs), medication assisted treatment (MAT), addressing maintenance of contact with a client regardless of housing status, and instructing administrators on the necessity of a robust referral network.

The virtual training includes recognition of barriers and evaluation of a case study during COVID. NASTAD notes stigma, access to care, language access, and medication prior authorization are the most common barriers to engagement, retention, and success in care. Challenges include, as we previously noted, a COVID-associated plummet in HCV testing, changes in working hours, the need to access facilities with ever changing rules of access, and technology barriers, especially for homeless clients. Successes include easier access to treatment thanks to flexibilities in insurance approvals, more easily tracking down and following up with clients thanks to “stay-at-home” orders, and easier contact tracing.

Resources at the end of the training materials are either national or based in/from New York City and prospective partners will need to consider adding to or substituting this resource list with their own, more local resources. NASTAD encourages accessing the program’s technical assistance and capacity building assistance teams and those of partners involved in developing program materials (also found in the resources section of the materials).

This model poses an opportunity that may only be limited by the will power of funders and willingness to collaborate in an environment where community-based organizations are encouraged to be everything to everyone. Funders should take note of the extraordinary potential NASTAD’s model offers and support both entities seeking to implement it and those entities implementing partners would need to rely on in order to fulfill the wrap around nature of care and navigation the model envisions.

Jen’s Half Cents: Family Courts, Child Welfare Services & Missed Opportunities for Intervention and Linkage to Care

One of the things I often relate in HIV advocacy and health care advocacy is the remarkable nature of the work we do. Yeah, we can absolutely get bogged down in the nuances of payment policies and necessary regulatory functions, but that’s not what motivates us. What truly drives us is a desire to improve the lives of those around us. And, as is the nature of any community built on shared trauma, HIV advocacy is unique in how it bonds us to one another. There’s little quite like it, regardless of the stakeholder. “On the ground”, we share about everything – our relationships, our hobbies, our sex lives, our triumphs and struggles, and, yes, our families. So nearly a decade into this work, it wasn’t a surprise–when I sought some emotional support—to find I could console with my colleagues as friends upon finding myself wrapped up in a complex custody battle. It brought me a great deal of comfort to receive advice on playing a supportive role to my partner as a parent and to share things like holiday photos and craft projects.

What did surprise me was coming to understand with great intimacy how family court and child welfare systems fail to consider their roles in family health, especially with regard to multi-generational poverty and behavioral risks. On February 6th, 2020, I was sitting in a court room awaiting a hearing while another parent’s case was being heard. The parent was seeking a change to a custody arrangement because the mother of his children had experienced a mental health break, was very likely to face homelessness, and he was making a concerted effort to both keep her involved in their children’s lives and to do so in a way that set her up for success. After his hearing concluded, he respectfully asked if the hearing officer or the court social worker could recommend resources for his ex to navigate public assistance and benefit applications. The response he received was, “we don’t know, we just don’t do that,” and I was shocked—truly and remarkably shocked—the court was unprepared for this request. It can’t possibly be an uncommon one. As he got up to leave, I politely stopped him and gave him information for a local federally qualified health center, Access Health Louisiana, which happens to be Ryan White funded.

This incident incited a shift in my perspective and self-education regarding issues of health, HIV-status, and family court and child welfare issues. A 2003 report from the ACLU’s AIDS Project found providers reporting clients having lost custody, denied visitation with their children, or having been barred from being foster or adoptive parents due to their sero-status. Indeed, parents have had their custody arrangements negatively impacted by merely associating with PLWH. In 2015, POZ Magazine covered the story of Donna Branum, a mother in Kansas who temporarily lost custody of her children because her fiancé’s HIV-status. While Branum was ultimately granted the right to return to a joint custody arrangement, the issue came to the attention of the court because Branum’s ex-husband petitioned the court, claiming Ms. Branum’s fiancé posed a “health risk” to the children. The ACLU’s 2003 report appropriately describes this type of stigma and lack of foundational, basic HIV-related education as discriminatory.

Thanks to a Supreme Court decision in 1998, HIV status, including “asymptomatic” cases, is covered under the protections offered by the Americans with Disability Act (ADA). While Bragdon v. Abbott centered on a dentist refusing to provide care for Sydney Abbott based upon her HIV status, the ruling contributed to the Department of Justice specifically mentioning HIV (twice) as a covered disability in its August 2015 guidance on the rights of parents and potential parents and technical assistance document regarding family courts and child welfare agencies:

Excerpt:

3. Who do Title II of the ADA and Section 504 protect in child welfare programs?

Answer: Title II of the ADA and Section 504 protect qualified individuals with disabilities, which can include children, parents, legal guardians, relatives, other caretakers, foster and adoptive parents, and individuals seeking to become foster or adoptive parents, from discrimination by child welfare agencies and courts. Title II also protects individuals or entities from being denied or excluded from child welfare services, programs or activities because of association with an individual with a disability. For example, Title II prohibits a child welfare agency from refusing to place a child with a prospective foster or adoptive parent because the parent has a friend or relative with HIV.

A 2013 UNAIDS report, entitled Judging the Epidemic, describes denying parents with HIV custody and visitation rights as “arbitrary, disproportionate and ineffective” with regard to any public health interest and urges courts to consider “actual” risk to a child’s welfare rather than “theoretical” risk. UNAIDS recognizes both children’s best interests and the rights of parents living with HIV as human rights issues needing careful address. However, even back in 1992, the book, AIDS Agenda: Emerging Civil Rights Issues, recognized family court matters provided an opportunity for “…the worst characteristics of litigants [to] emerge, with divorcing parents raising issues based on prejudice rather than on concerns of parenting ability – out of their own bias, anger, or an attempt to appeal to the anticipated biases of judges.” Both sources cite the American Bar Association’s position defending the rights of parents living with HIV and legal precedents in which parents living with HIV needed to employ medical experts to explain what’s commonly understood in medical circles: it is impossible to transmit HIV via casual, household contacts.

I’d be remiss not to mention a growing area of study currently gaining more attention: how—both psychological/emotional and physical—abusers use family court processes to exert control over their intended victims. At the intersection of family court processes being abused and parents living with HIV is the decade-old Centers for Disease Control report on domestic/intimate partner violence as “…both a risk factor for HIV, and a consequence of HIV.” This area deserves more attention than it gets; the least of which being a follow-up and more recently updated data than is provided in the CDC report.

In fact, despite attention to educating children and families and providing a holistic approach to outreach and linkage to care, the National HIV Strategy doesn’t mention family courts or child welfare agencies even once. With the HIV epidemic disproportionately impacting Black Women, family courts and child welfare agencies have a very unique opportunity as non-traditional partners to impact the public health of their communities. However, to even begin doing this, family court judges and child welfare agencies would need to begin addressing policies and procedures that essentially penalize poverty (often confusing poverty with negligence), rather than assisting families in need.

“We recognize the lives of PLWH are often impacted by people not working in HIV,” Louisiana’s implementation of their Ending the HIV Epidemic plan, Get Loud Louisiana, states. The plan is the first (to my knowledge) to include activities to engage family courts, social workers, and child welfare agencies to educate and change policies to better serve this public health interest.

Like all issues surrounding HIV, this is an intersectional one. Well-established is the role and social support of family for people living with HIV, and family court’s primary mission is the health and well-being of families; policies and procedures for resource-sharing are of paramount importance in meeting both of these sets of needs. To end the epidemic, to set families up for success, to address stigma, to help keep PLWH engaged in care, and so much more, we must begin to engage these critical stakeholders. We cannot afford to continue to miss this opportunity.

Ongoing Viral Hepatitis Outbreaks: Systemic Interventions

Viral Hepatitis outbreaks, namely Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B, have been in the news quite a bit during the last year. Could COVID-19 have contributed to them?

Annual surveillance data for the state of Florida found the 2017 Hepatitis A outbreak has shifted location from primarily South Florida to the Pensacola area, in Escambia County. Florida isn’t alone with persistent Hepatitis A outbreaks. According to the CDC’s Hepatitis A outbreak dashboard, as of February 5, 2021, almost 40,000 cases of Hepatitis A have been confirmed related to the outbreak beginning in 2017, with more than 25 states still in an active outbreak status. Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, and West Virginia top the list for the most cases reported since the outbreak began.

These outbreaks are primarily attributed to an increase in homeless populations and populations experiencing housing instability and lack of access to sanitary conditions. Hepatitis A is primarily transmitted in close-contact settings by way of ingesting blood or stool particles from a person carrying the disease. While the disease is not always deadly, it can be. Indeed, the 2017 multi-state outbreak has resulted in at least 354 deaths, according to the CDC.

Additionally, in late 2020, Vermont reported outbreaks of Hepatitis A and B, with Vermont Health Commissioner, Dr. Mark levin, said the state had been anticipating an eventual outbreak because of existing outbreaks in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Hepatitis B, much like Hepatitis C, is often attributed to injection drug use, long-term health care settings, and contact with bodily fluids containing the virus, including blood and semen.

In response to these outbreaks, the CDC has encouraged states to engage in more active community education and vaccination programs. Both Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B are preventable and post-exposure vaccine administration may be appropriate in some situations. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic has reminded us, other interventions are necessary to address both risk factors to infectious diseases and reduce barriers to care. Addressing the nation’s housing and homelessness crisis could potentially provide one, extraordinarily significant structural intervention to address these and other public health crises.

President Joe Biden made campaign promises relating to need for more equitable housing policies and expanding affordable housing to address social justice needs as well as health-related needs and is already working to establish a fairer housing environment for the country. From extending the eviction moratorium to ensuring housing protections are extended to all Americans regardless of sexual identity or gender orientation (a reversal of the previous Administration’s policies), first steps are already being laid in order to meet well-known housing needs. And none too soon, as we don’t yet have a full picture of exactly how the COVID-19 caused economic recession will impact rates of homelessness, but one study issued a rather dire warning last month, saying this recession would likely cause double the rate of homelessness than the 2008 crisis.

From Hepatitis A and B to COVID-19 and the Opioid Crisis, housing has become (always was) a preeminent intervention that remains largely inadequately addressed. Federal funding and state programming must move to invest in housing as a prevention strategy in order to get ahead of these outbreaks and stop the chains of transmission. Housing is not just a human necessity; it is a public health necessity and must be embraced with the vigor the moment demands.

For the most up-to-date information from the National ADAP Working Group (NAWG), Hepatitis Advocacy, Education, and Leadership blog, and the quarterly HIV-HCV Co-infection Watch Report, sign up for our listserv here.

The Future is Now: Welcome to the Age of Injectables

For years, HIV advocates have anticipated injectable antiretroviral therapies (ART) – often with a level of excitement. I recall listening to robust discussions between advocates and officials in statewide meetings, reviewing candidate treatments, discussing labor and staffing needs for providers, potential regulatory changes needed to ensure programs could cover the actual syringes associated with injectable ART, given state-based restrictions. The excitement extended from a sense of no longer needing daily tablets (pills) in order to maintain adherence and thus an undetectable viral load, extend quality of life for those experiencing barriers to care like homelessness, and otherwise welcome a new age of treatment – if only by new method of delivery.

In late 2019, we seemed on the edge of such an accomplishment. ART focused pharmaceutical manufacturers Glaxo Smith Kline subsidiary, ViiV, and Johnson & Johnson subsidiary, Janssen, had paired up in an effort to provide the world with its first long-acting ART via injection. However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) refused to grant the companies an approval for the dual shot regimen of cabotegravir and rilpivirine (together, “Cabenuva”) due to concerns related to “Chemistry Manufacturing and Controls”. Thirteen months later, on January 21, 2021, Janssen and ViiV announced FDA approval of Cabenuva.

ViiV Healthcare understands the transformative nature of Cabenuva and the many “firsts” associated with a provider-administered injectable therapy for HIV. We will be educating HCPs on how to identify appropriate patients who may prefer or benefit from an option other than daily, oral therapy. Two key considerations are that patients agree to the required monthly dosing schedule and understand the importance of adherence to scheduled dosing visits. We also will be helping educate people living with HIV about Cabenuva and these commitments. - ViiV

According to the product monograph, Cabenuva is a dual intramuscular injection protocol (requiring one shot of cabotegravir and one shot of rilpivirine) monthly, administered by a health care provider. Prior to starting the monthly injections, providers should test tolerability via “oral lead-in” via once daily tablets of both cabotegravir and rilpivirine with a meal. If consumers expect to miss a monthly injection by more than 7 days, once daily oral tablets of cabotegravir and rilpivirine may be used to replace the injections for up to two injection cycles (or 2 months). Contraindictions include any known or suspected resistance to either or both drugs and any intolerability of components of either or both drugs. The injections cannot, at this time, be self-administered.

Despite all of the antici…pation and data showing a higher level of satisfaction than with current regimens among trial participants, some advocates are still cautious and concerns remain regarding logistical accessibility. Regarding financial accessibility, ViiV has already launched its patient assistance program for Cabenuva through ViiVConnect. Florida advocates and members of Florida HIV/AIDS Advocacy Network, Ken Barger, Joey Wynn, and David Brakebill, discussed in…spirited detail varying perspectives on rural access.

Wynn advocated for diversifying public funds, if rural health departments couldn’t meet the demand of a once monthly injection protocol, “If a rural health department can’t do a monthly injection [for ART], when they do injections for all sorts of other disease states, they need to give their money to providers who can.” Barger and Brakebill pointed out that for many rural counties, the health department may be the only provider in the area that’s accessible, with a highlight on concern regarding capacity. Wynn suggested the need for investment in better planning and preparation – not just for injectables, but for situations of natural disasters which have been known to disrupt access to medications and care in the state regularly.

When asked about these concerns, ViiV acknowledged the challenges and provided the following commitment to invest in ensuring more equitable access to care: ViiV Healthcare is also dedicated to improving how HIV treatment and care are delivered in the “real-world” environment through our Implementation Science program. One example of this focus is a study evaluating how improvements in transportation and use of digital tools can help get people living with HIV to their healthcare providers on a regular basis, which if successful we’ll look to implement on a broader scale

This week’s HEAL blog wouldn’t have been possible without the coverage of and reporting on treatment developments in this and other therapeutic areas by Liz Highleyman.

Quotes attributed to ViiV Healthcare are direct and were provided by Robin Gaitens, Product Communications Director.

Highlights from the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan

On January 7th, the Department of Health and Human Services announced publication of an updated plan to eliminate viral hepatitis in the United States. This “roadmap” coincides with HHS’s release of the first Sexual Transmitted Infections (STI) National Strategic Plan on December 18th, 2020, and an update to the HIV National Strategic Plan on January 15th, 2021.

Notably, these documents reference one another and specifically call for integrated efforts to tackle these syndemics across stakeholder groups, specifically including substance use-disorder as part of a “holistic” cohort. Additionally, each contains a near identical vision statement:

- The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination.

- The United States will be a place where new HIV infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with HIV has high-quality care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination.

- The United States will be a place where sexually transmitted infections are prevented and where every person has high-quality STI prevention, care, and treatment while living free from stigma and discrimination.

All three vision statements end with the following: This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance.

Each plan addresses a limited but indefinite list of social determinants of health such as socio-economic burdens impeding access to care, including racism, intimate partner violence (IPV), and stigma and acknowledges discrimination against sexual and gender minorities (SGM). COVID-19 is mentioned repeatedly as underscoring and providing a highlight to the United States’ excessive health disparities, giving a nod to the unfortunate…”opportunity” the pandemic has provided health care advocates working with or as a part of these highly affected, highly marginalized communities. “The pandemic has exacerbated existing challenges in the nation’s public health care system, further exposing decades, if not centuries, of health inequities and its impact on social determinants of health.” Plans also acknowledge personnel and resources from programs addressing STIs, viral hepatitis, and HIV have been heavily redirected toward efforts to address COVID-19.

All plans call for better data sharing across providers and reporting agencies and an increase in surveillance activities, with an emphasis on local-level efforts to rely on local data, rather than national-level trends. Each plan also calls for expanded testing, interventions, linkage to care, provider and community education, and access to treatment, including incarcerated populations. The Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan (VHNSP) described “poor quality and a paucity of data” as clear impediment to meeting the goals of the plan. Sparring no stakeholder with access, the plan highlights a need for data sharing among correctional programs, health insurers, public and private health systems, mental and behavioral health, public health entities, and more.

The VHNSP also acknowledges opportunities to take lessons from the fight against HIV and the need to integrate “treatment as prevention” as a powerful tool in combating new HBV and HCV infections.

The Viral Hepatitis Strategy National Plans notes the following key indicators:

On track for 2020 targets:

HBV deaths

HCV deaths

HCV deaths among Black People

Trending in the right direction:

HBV vaccine birth dose (87% for people born between 2015-2016 by 13 months, WHO recommends 90% by 13 months)

HBV vaccine among health care personnel

HBV-related deaths among Black people

HBV-related deaths among people over the age of 45

Not on track:

New HBV infections

New HCV infections

New HBV infections among people 30-49 years of age

HBV-related deaths among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders

New HCV infections among people of 20-39 years of age

New HCV infections among American Indians and Alaska Natives

The plan recognizes an 71% increase in HCV infections in reporting years 2014-2018 and points toward a strong data correlation between these new infections and the opioid epidemic, based on local area reporting data. Care related challenges include lack of personal status knowledge, perinatal transmission, and cost of curative treatment.

The plan states ideal engagement in various activities across an astoundingly broad scope of stakeholders including faith-based organizations for outreach and education, stigma and anti-bias training among all client-facing personnel, the opportunity to engage comprehensive syringe services programs as an outlet to provide HCV medication and more traditional services like referral for opioid-use disorder, educating providers and employers about federal protections for people with viral hepatitis, increasing awareness through school education programs – specifically culturally sensitive and age-appropriate sex education programs.

From issues of criminalization laws to lack of cohesive data collection, overall, the plan is very welcomed, comprehensive approach toward addressing viral hepatitis. With the STI and HIV plans mirroring very closely.

While the plans call stakeholders to address economic barriers to care and other social determinants of health, specifics are lacking. Stakeholders may wish to consider some of the priorities in the Biden administration’s public health approach including hiring from affected communities (including reducing or allowing alternative education requirements like live-experience or consideration of on-the-job training opportunities). These lofty goals may also require regulatory changes in order to implement and realize them fully (i.e. mechanisms incentivizing correctional facilities and the Veterans Administration to share data with local or state health departments and establish linkage to care programs). Private funders would be wise to take advantage of this opportunity and fund innovative, comprehensive pilot or demonstration projects. Advocates would be wise to leverage these documents when seeking state-level regulatory changes and advocating for federal funding and program design.

HCV Screenings: An Evolving Blind Spot Amid Covid-19

We cannot afford to allow COVID-19 to detract from efforts to address existing syndemics.

A recent study in the Journal of Primary Care & Community Health highlighted the impact of COVID-19 on routinized Hepatitis C (HCV) screening in ambulatory care settings. (Press release and summary of study findings by the Boston Medical Center can be found here.)

Before we dig into the findings, some background:

On April 10, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued expanded recommendations regarding Hepatitis C Virus screenings to include universal screening for adults aged 18 and over at least once in a lifetime and all pregnant persons – except in settings where HCV prevalence is less than 0.1%. The recommendations also calls for periodic screening among people who inject drugs (PWID).

Prior to this update, the previous recommendations (2012) for HCV screenings was primarily limited to an age cohort focused on Baby Boomers (adults born between 1945 and 1965, regardless of risk factors) and certain risk factors including potential for occupational exposure.

These recommendations came on the back of the CDC’s Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report (2003-2018), indicating a rise in acute HCV infections among all age cohorts except those under the age of 19, with PWID representing the leading risk factor for new HCV infections (72%). However, data collection on both acute HCV infections and risk factors is sorely lacking. The 2018 surveillance report notes Alaska as having no statutory or regulatory reporting requirement, Hawaii did not report data to the CDC for any year of the report, and 6 other states merely indicated as “data unavailable” (most typically for all reporting years). Finally, no state reported a sero prevalence below 0.1%.

In a report entitled Beyond Baby Boomers, the CDC notes the surge in new HCV infections was dramatically impacted by the opioid crisis – a driving cause in new infections among younger cohorts.

Despite these recommendations, health care providers and traditional health care settings like primary care providers and hospitals routinely miss opportunities to identify PWID and offer HCV screening. This leaves emergency rooms and comprehensive syringe service providers as the most critical partners in identifying new HCV infections, with a priority in op-out screening as a means to increase surveillance, linkage to care, and stigma-reducing education.

All of this makes the Boston Medical Center study that much more alarming. The COVID-19 pandemic, while bringing much to us in the way of innovative health care access, has drastically decreased HCV screening in ambulatory care settings in part because of the leading innovation: telemedicine. Authors observed a hospital-wide reduction in HCV screenings by 50% and diagnoses of HCV by 60%. The finding was even more striking in primary care settings at 72% decrease in HCV screenings and a 63% decrease in new diagnoses. While HCV screenings are not the only preventative care to suffer, as noted by the authors, this is particularly concerning because of the nature of infectious disease impact on public health and because chronic HCV is the leading cause of hepatic illness in the United States.

The blind spot on the horizon is our less than proactive approach in directing resources and programing. Primarily, as many are learning thanks to COVID-19, data collection is historical in nature and offers a limited ability to predict where these necessary resources should be targeted, both geographically and demographically. Data collection efforts may need to consider other metrics in addition to screening and surveillance data in reviewing where resources and programs should focus as we move through the pandemic (i.e. fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose data). Given the CDC’s acknowledgement of the role the opioid crisis has had in driving new HCV infections, the agency’s December 2020 press release indicating an increase in overdose deaths associated with COVID-19 is all that more concerning.

Finally, advocates working at varying intersections of addiction, harm reduction, HCV, HIV, and overall health care could aim their efforts at state and federal policy influencers associated with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to call for including HCV screening as a standard of care for all ambulatory care providers, either by incentive or penalty, as applied to approved Marketplace plans. Other avenues for this strategy should include other state insurance regulatory bodies.

We cannot afford to allow COVID-19 to detract from efforts to address existing syndemics.

What a Narrowly Divided Senate Means for Health Policy

On January 5th, Reverend Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff defeated Senators Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue in the Georgia Senate run-off elections, respectively. Democrats narrowly winning both Georgia Senate seats also means Democrats have narrowly won the Senate, dividing seats 50-50 between members who caucus with Democrats and Republicans with Vice President-elect Harris empowered to cast any tie-breaking votes and handing the incoming Biden administration a unified government.

While those with lofty ambitions on policy and legislative issues are cheering, there’s good reason to consider the need for moderating what can be expected from the 117th Congress: Democrats aren’t always on agreement on major issues like direct payment amounts as part of COVID relief or Medicare For All. The Biden administration will likely need to rely heavily on the regulatory powers allowed to federal agencies – which makes the prospective appointment of Xavier Becerra to lead Health and Human Services make more sense than it perhaps did on the surface. After all, who appoints an attorney to lead a health care agency?

The Trump administration made dramatic regulatory moves with regard to health care, targeting non-discrimination rules in health care, the Affordable Care Act including attempting to get the legislation declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, drug pricing, and championed legislative changes eliminating individual mandate penalty. While a judge has already temporarily blocked Trumps’ effort to tie drug prices to that of other nations’ prices and the Supreme Court has given the green light to recently-revived Food and Drug Administration rules on abortion pill access, these issues are regulatory in nature. The Biden administration could simply choose not to defend these moves in court change these regulations. While state push back is likely, a lack of Congressional challenge against these moves may help smooth the way for institutional changes.

It’s largely expected that among Biden’s first moves regarding health care will include expanding COVID relief measures and vaccine distribution plans, rescind the Mexico City policy (also known as the “Global Gag Rule”), “expand[ing] access to high-quality health care for Lesbian, Gay, Biden, Transgender, and Queer+ individuals” (or moving quickly to rescind the “Provider Conscience” rule), and reversing the 23% rate cut to 340B entities. With the help of a unified House and Senate, among Biden’s first accomplishments may be a legislative “fix” to the Affordable Care Act challenge awaiting ruling from the Supreme Court. Other campaign promises from Biden include seeking legislation to end HIV criminalization and increasing research into harm reduction models, expanding syringe services programs, and substance treatment funding – an issue Biden has evolved on and largely due to bearing witness and supporting his son through.

Other moves to watch for:

Strengthening the Affordable Care Act:

- A regulatory move recalculating and increasing subsidies for Marketplace plans

- Restoring Marketplace Navigator funding

- Returning the open enrollment period to 90 days

- Rescinding a proposed rule on 1332 waivers allowing states to opt-out of the Marketplace

- Changes to regulations regarding short-term policies and association health plans (including reduced allowable coverage periods and requiring coverage of pre-existing conditions, including pregnancies, HIV, HCV, and transgender identity among others)

- Reduce documentation burden for subsidies and Special Enrollment Periods

- Expand the definition of qualifying life events and rules regarding special enrollment periods

- Enforce mental health and substance abuse coverage parity

Strengthening Medicaid:

- Rescind, reject, and stop defending 1115 waivers seeking work requirements

- Encourage 1115 waivers to include the impacts of increasing coverage

- Revise increased eligibility verification for Medicaid

- Encourage policies regarding presumptive eligibility outside of hospitalization and emergency situations

- Review and revise reimbursement schedules for Rural Hospitals

LGBTQ Health Equity:

- Issue guidance and seek funding to address mental health services and support staff in schools

- Reinstitute and/or strengthen Obama era guidance regarding transgender students and Title IX protections

- Revise and strengthen Affordable Care Act, Section 1557 non-discrimination rules protecting women, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer people, and people living with pre-existing conditions like HIV or HCV (in which the Trump administration would allow payers and providers to refuse care

- Rescind the Trump era ban on transgender people serving in the military

- Reverse or rescind Trump era “religious conscience” applying to civil rights laws – use regulatory power to include Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer people in civil rights protections in health, housing, and labor

- Expanding data collection policies to include sexual and gender identities

While some may view the heads of regulation making agencies as “unelected officials”, in many ways, who we elect to be the executive is very much choosing who leads the agencies that impact our lives on a daily basis. There is much work to do for the Biden administration on the regulatory front and unified, carefully crafted legislation speaking to these issues may well help cement these changes beyond political party ping pong.