The Only Thing That Stays The Same… Welcome to 2026

I want to personally thank those of you who joined me in finishing the sentence that is this week’s blog title.

For CANN and many of our colleagues and partners, 2025 was indeed the year of significant change. From government institutions being shook to their core—a near unprecedented challenge to our societal agreements on “fact”—to our dedication to issues and community through education and growth, who we are today is not who we were on January 1, 2025. And, despite what reflection of harder and more stressful moments might tell us, that change is not necessarily a bad thing.

2026 greets CANN, as an organization, with our own evolution: even as we seek to evolve the policy landscape and our partners to be patient-focused in an ever-increasingly tangible way.

CANN’s growth means permanent work for some of our contractors, allowing for incredible investments in three astounding individuals and their continued development as trend setters and thought leaders. Along with conversion to employee status, Ranier and Kalvin’s roles are expanding to leverage their state-based successes and networks to include federal policy education and advocacy. Travis’s expanded position will find him focused on ensuring CANN’s image is uniform, polished, and properly presented to the world at large. Our friends at Perry Communications are continuing as collaborators in shaping the advocacy ecosystem as patient-driven without fear or favor to the influences impacting access to care.

Our community investments are also growing and evolving in exciting ways. Later this year, CANN will share details on our re-vamped Community Roundtable events and how the “PDAB Summit” will transform into a broader conversation on patient access, drug pricing, and necessary reform and regulation. This discourse will offer real solutions that serve patients rather than simply catering to the next round of shady middlemen or market manipulating investors.

Growth and change is never all easy. The nature of evolution often demands the…unfamiliar.

After twelve years of service to CANN, Brandon Macsata will be moving on to focus on his work with ADAP Advocacy and PlusInc. After coming on to assist CANN’s founder, Bill Arnold, with restructuring the organization in 2014, Brandon continued to shepherd the organization through Bill’s death, including recommending me to the Board as successor CEO. Brandon’s contributions to CANN are immeasurable and we’re grateful for his care in helping us get to here.

This year is CANN’s 30th anniversary and much like any person turning thirty years old, we’ve been steadily evaluating our role, our knowledge, and our power to positively effect change. In 2025, we issued four $10,000, low-barrier advocacy grants to state-based and national partner organizations working on our shared issues from different perspectives. These organizations, Lupus Colorado, Aging and HIV Institute, Pharmacists United for Truth and Transparency, and Epilepsy Alliance of Louisiana, share our mission to define the issues impacting patient access to care across all health conditions and regardless of a patient’s socio-economic status, race, sex or gender, religion, geography, or their health history. We learned from these organizations about services they offer, treatment development pipelines, perspectives on navigating care coverage across programs, challenges in keeping local pharmacy doors open, and how providers, even in schools, can refuse to administer life-saving medication to a child experiencing a seizure simply because they are uncomfortable with the medication determined to be the standard of care. We shared our perspectives on messaging and leveraged our experience in HIV exceptionalism to navigate policy change and demand equitable care for our shared communities.

Because the reality is that HIV is losing its exceptional nature in the policy realm. While our programs remain alive—and, frankly, as of yet still funded—our support systems and our integration into broader, more generalized care as a manner of ensuring actual access for people living with HIV (those systems and changes for which we’ve advocated), are under threat by short-sighted, single-issue discussions. Advocacy organizations who have collected money over the years without innovation or growth will continue to labor without producing results and at the expense of true change-makers. Those who expect to proceed according to their own status quo, mired in bureaucracy, the successes of the past, and without authentic coalition-building will atrophy. Again, that’s authentic coalition-building: as I’ve shared over the years, “we must find friends”. And I don’t mean transactional friends (i.e., “If you sign this letter, I’ll sign yours”), but rather real relationships built in a slower manner that develops attachment without expectation of specific action, and instead deep enough care to show up when a call is made.

This goes beyond our community partners. Our industry partners are facing much the same conversation about the therapeutic areas they invest in and their alliances with advocates. What does it mean to be more than funders? What does it look like to fundamentally transform the patient advocacy ecosystem through stabilizing investments? What does it mean to support incubator models of advocacy? How does this impact or otherwise become integrated into a company’s business model? The answers to these questions are not static and they are far beyond any quarterly stockholder assessment, and our partners know this.

Advocates, for our parts, must be responsive to a rapidly-changing environment where those most confident in their proposed “solutions” are only having half the conversation on a single-issue within a larger web of issues, networked in a complex chain reaction of impacts. The consequences of policymakers—state and federal—suffering from “tunnel vision” or engaging in cheap, inaccurate, and deceptive talking points are manifesting in readily foreseeable conflicts making their way through expensive and unnecessary legal battles at the expense of tax dollars and patient quality and affordability of care.

We can do better than this. As HIV advocates, we know how to leverage historical challenges into future successes. We know how to seek out the unforeseeable and to respond to clever callousness. We have an obligation to share this knowledge and empower partners across the country to achieve what we have and, in doing so, to save our own investments from today’s threats.

2026 requires a paradigm shift from institutional comfort to nimble, responsive, powerful advocacy.

The changes 2025 brought us will be the continued challenges of 2026. To which the answer must be “We can.” (…CANN)

How Lupus Colorado and CANN Built an Advocacy Powerhouse

Some partnerships start with a formal strategy session. Ours began with a simple realization. People living with lupus and people living with HIV or viral hepatitis face many of the same obstacles when they try to get the care they need. Once we recognized that shared landscape, the connection between Lupus Colorado and the Community Access National Network (CANN) started to feel not only natural, but necessary.

CANN’s mission is to define, promote, and improve access to healthcare services and supports for people living with HIV and people living with viral hepatitis. The focus is on keeping care affordable and within reach for people no matter where they live, what they earn, or how they are insured. As soon as we spent time together, it was clear how much that mission speaks to the lived reality of people living with lupus. Many in our community depend on the same safety net programs, the same specialty pharmacies, and the same policies that protect medication access for people with chronic conditions nationwide.

Once we began sharing stories, the overlap came into full view. We heard about people living with lupus who rely on the 340B Drug Pricing Program to keep their treatment affordable. We heard about people managing both lupus and other long term conditions who face the same hurdles that people living with HIV or hepatitis encounter when insurance rules change or formularies shift. We also heard how uncertainty about programs like the 340B Program or state efforts to set Upper Payment Limits through bodies like the Colorado Prescription Drug Affordability Board creates stress and confusion for everyone who counts on steady access to treatment. The policy language may sound technical, but the effects show up in daily life. That shared experience became the spark that brought our organizations together.

Lupus Colorado eventually became a kind of testing ground for patient engagement around these issues. When debates surrounding 340B and the state board intensified, we invited our community to learn more and speak up. People living with lupus stepped forward with thoughtful questions about what these changes might mean for their medications and their stability. They shared stories about years spent finding the right treatments. They talked about the worry that comes with not knowing whether a familiar pharmacy or discount program will still be available. Their honesty helped shape a clearer picture of what access really means for people with chronic conditions.

CANN supported this work by offering context, training, and a strong national network. Their experience showed us how these local conversations fit into broader public health goals, including ongoing efforts to build sustainable systems for people living with HIV and long term strategies for hepatitis C elimination. They also helped amplify our stories by connecting them to advocates, policymakers, and public health leaders who are working to protect and expand medication access nationwide.

As we continued working together, the partnership grew into something that felt like friendship and, at times, even family. It surprised all of us how quickly Louisiana and Colorado began to feel connected through shared purpose and shared energy. This work is deeply personal, and when good people come together with the belief that collaboration, not competition, brings out our strongest work, something close to magic begins to take shape. My curiosity and strategic thinking blended naturally with Jen’s mentorship and policy insight. Kalvin and Ranier added necessary context for any variety of issues we shared and even accompanied me to some meetings to ensure Lupus Colorado's interests were well-defined for our audience. Together we created a combination that strengthened every effort that followed.

This collaboration also changed how advocacy feels for many people. Instead of seeing policy as something decided far away, our community began to see it as something they can influence. When people speak about their lives, policymakers listen differently. The technical language becomes human. The stakes become easier to understand. And the entire conversation shifts toward solutions that protect access rather than limit it.

The partnership between Lupus Colorado and CANN has shown us that when organizations connect around shared purpose, everyone benefits. We bring different histories and different areas of expertise, but we are united by our commitment to ensure that people living with chronic conditions can access the care they need without fear or financial hardship. Our collaboration continues to strengthen advocacy networks, uplift patient voices, and support progress toward public health goals that matter to all of us.

Most of all, this partnership reminds us that no one faces this journey alone. When communities work together, even unlikely collaborations can grow into something powerful enough to spark change.

Antibiotic Crisis: Hope Amid Institutional Decline

The fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) stands at a critical crossroads. Despite a slight decline in U.S. STI rates in 2023, resistance to antibiotics continues to rise globally, particularly for gonorrhea. This creates a paradox: while we're seeing promising new treatments advancing toward approval, recent political decisions have dramatically weakened our ability to track resistance patterns. Meanwhile, funding and policy support for developing new antibiotics remain inadequate. This crisis demands urgent attention as resistant infections spread faster than new treatments can be developed, with serious implications for public health and patient care.

The Growing Threat of Antibiotic-Resistant STIs

For people living with chronic conditions or compromised immune systems, antibiotic-resistant STIs aren't just a public health statistic—they represent a serious and growing threat to wellbeing. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported fewer gonorrhea cases in the U.S. last year, the global picture is far more concerning.

Gonorrhea is becoming increasingly resistant to our last effective treatments. In Southeast Asia, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified a three-fold increase in extensively drug-resistant gonorrhea strains in Cambodia between 2022 and 2023. These hard-to-treat infections now make up over 12% of cases in the region.

What does this mean for patients? When first-line treatments fail, people face longer infectious periods, more complex and expensive treatments, and greater risk of complications. For people living with HIV or hepatitis C, these resistant infections can further compromise health and complicate disease management.

Breakthrough Treatments on the Horizon

Despite the grim outlook, two novel antibiotics represent genuine breakthroughs in the fight against resistant STIs after decades without new gonorrhea treatments.

Zoliflodacin, developed through a Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership (GARDP) and Innoviva Specialty Therapeutics partnership, completed the largest Phase 3 trial ever conducted for gonorrhea, with promising results. While its 91% cure rate appears slightly lower than the current standard's 96%, zoliflodacin's significance lies in its novel mechanism of action against resistant strains and its oral administration route. As resistant gonorrhea increasingly requires injectable treatments, an effective oral option represents a major advance for both accessibility and patient care.

Equally promising is gepotidacin, developed by GSK and already FDA-approved for urinary tract infections as of March 2025. This novel antibiotic showed a 92.6% success rate against gonorrhea through its unique dual-targeting mechanism that inhibits two critical bacterial enzymes, making it effective against resistant strains. GSK plans to submit for the gonorrhea indication later in 2025.

These developments showcase complementary partnership models: GARDP's non-profit approach ensures zoliflodacin's availability in low-income countries, while gepotidacin demonstrates successful public-private partnership between GSK and BARDA. Despite these advances, the WHO reports the broader antibiotic pipeline remains critically thin, with only 12 truly innovative antibiotics among 32 in development, and just 4 targeting the most critical pathogens.

Political Decisions Undermining Public Health

In a dangerous contradiction, just as resistance is rising and new treatments are on the horizon, political decisions have severely weakened our ability to monitor and respond to these threats.

Since early 2025, the current administration has eliminated approximately 20,000 jobs across health agencies and proposed cutting the HHS budget by about 26% ($127 billion).

The impact on STI programs has been particularly severe. The Washington Post reported that all 27 scientists at the only U.S. facility capable of tracking hepatitis outbreaks were fired. Additionally, 77 CDC staff members working on STI prevention were let go, including 49 experts embedded in state health departments who provided critical support to local efforts.

Most alarming for people at risk of STIs is the closure of the specialized lab that tests gonorrhea samples for antibiotic resistance. This lab was our early warning system—without it, doctors and patients won't know which antibiotics still work until treatment failures start mounting.

Prevention Strategies: Interrupting Transmission Chains

While developing new antibiotics is critical, prevention remains essential. Doxycycline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (DoxyPEP) has emerged as an effective tool for breaking transmission chains. The CDC now recommends that men who have sex with men and transgender women with a history of bacterial STIs use DoxyPEP after sexual encounters.

Real-world data from San Francisco showed significant declines in chlamydia and syphilis among those using DoxyPEP, though gonorrhea reductions were less dramatic. While some concerns exist about the potential for DoxyPEP to contribute to broader antibiotic resistance, current evidence suggests this approach can effectively reduce STI transmission in high-risk groups—a crucial tool while we wait for new treatments.

The Funding Gap and Market Failure

The fundamental problem in antibiotic development is an economic one: the market doesn't adequately reward the creation of new antibiotics, especially those held in reserve to combat resistance.

The experiences of both zoliflodacin and gepotidacin highlight this challenge. Zoliflodacin required non-profit involvement through GARDP to advance through clinical trials, while gepotidacin needed significant government funding through BARDA. As Henry Skinner of the AMR Action Fund notes, "The funds needed to support this ecosystem, particularly in late-stage development, won't be there in a couple of years unless something unanticipated happens."

The AMR Action Fund, backed by pharmaceutical companies, aims to invest $1 billion to bring 2-4 new antibiotics to patients by 2030. The Fund has deployed over $100 million in capital to companies developing promising antimicrobials. However, experts recognize this as a stopgap measure rather than a solution to the underlying market failure.

A more sustainable approach is proposed in the PASTEUR Act, which has been introduced in multiple congressional sessions without passing. This legislation would create subscription contracts with developers of critical antimicrobials, ensuring financial returns regardless of how sparingly the drugs are used—essentially paying for access rather than volume.

This "Netflix model" for antibiotics would help align public health needs with market incentives. However, despite bipartisan support, the Act faces an uncertain future in the current political climate of budget cutting and deregulation.

Disproportionate Impact on Vulnerable Communities

Antimicrobial resistance operates within complex syndemics, where multiple health conditions interact and amplify each other within populations experiencing social inequities. People living with HIV stand at the intersection of these overlapping epidemics.

Research shows people living with HIV have higher rates of drug-resistant gonorrhea co-infection, each condition worsening the other. This syndemic intensifies with hepatitis C—a Department of Veterans Affairs study found 37% of people with HIV were also HCV-positive, with significantly higher rates of mental health issues and substance use disorders among these co-infected patients.

Among people who inject drugs with HIV, HCV rates reach up to 71% in some settings, according to a global review. These aren't coincidental occurrences—structural factors create environments where these epidemics cluster and interact.

The dismantling of surveillance infrastructure creates a dangerous blind spot in tracking these syndemics. Without specialized CDC labs monitoring resistant gonorrhea, we've lost our early warning system for emerging resistance patterns in vulnerable communities. Simultaneously, new restrictions on health equity research effectively discourage scientists from studying social factors that increase vulnerability to antimicrobial resistance.

A Patient-Centered Path Forward

From a patient and advocate perspective, five key policy areas require immediate attention:

Restore critical infrastructure. The dismantling of STI surveillance labs has left both patients and providers flying blind. Congress must fund restoration of these capabilities and hold administration officials accountable so we can track resistance patterns, update treatment guidelines, and support state and local health departments.

Support innovative development models. The GARDP partnership for zoliflodacin and the GSK-BARDA collaboration that produced gepotidacin demonstrate effective approaches to antibiotic development. These models—balancing commercial viability with public health needs—warrant expanded funding and replication.

Implement pull incentives. The PASTEUR Act would create a subscription-based model rewarding companies for developing critically-needed antibiotics without encouraging overuse, aligning market incentives with public health priorities.

Strengthen integrated care models. People at highest risk of resistant infections often face multiple health challenges. HIV, HCV, and STI services should be integrated to address overlapping needs, following the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program's comprehensive care model.

Expand prevention strategies. While new treatments are essential, preventing infections reduces suffering and limits resistance. Expanded access to DoxyPEP, increased STI screening in high-risk populations, and vaccine research represent critical prevention strategies.

The antimicrobial resistance crisis in STIs reveals a stunning act of self-sabotage: just as scientific innovation finally delivers promising new treatments like zoliflodacin and gepotidacin, the misguided decimation of public health infrastructure has crippled our ability to track and respond to resistant infections. This isn't poor timing—it's the cavalier dismemberment of critical surveillance systems by ill-equipped partisans wielding policy chainsaws with no regard for consequences. The resulting wreckage threatens to undo decades of progress against STIs, particularly for communities already navigating systemic barriers to care.

The path forward demands both hope and principled outrage. Patients and advocates must forcefully reject further cuts to public health infrastructure, demand immediate restoration of STI surveillance capabilities, and hold elected officials accountable for the consequences of their decisions. We must insist on passage of the PASTEUR Act to fix the broken economics of antibiotic development while ensuring that promising science reaches those who need it most, not just those with wealth, power, and access.

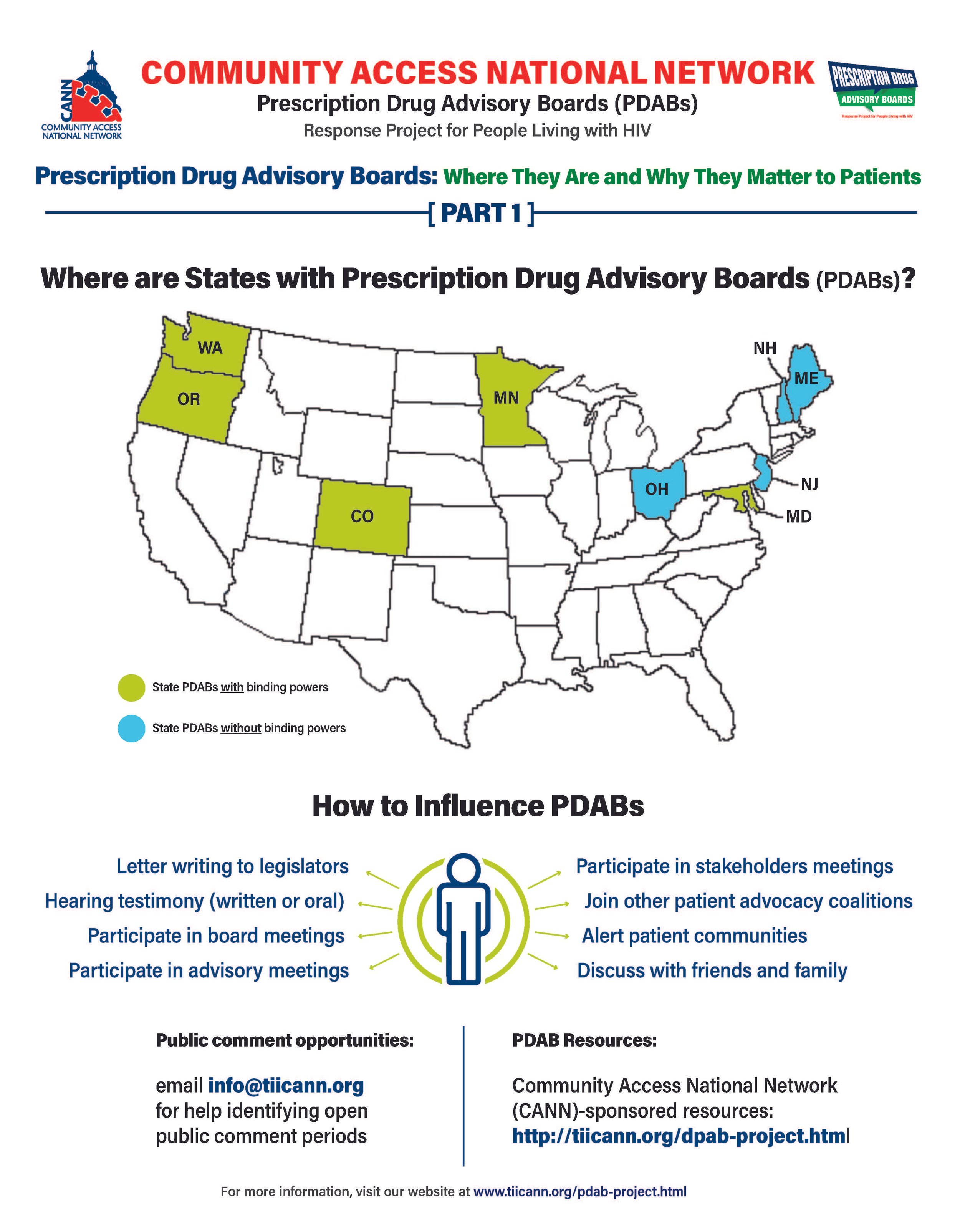

PDAB Chicanery: How Drug Affordability Boards Are Undermining Public Engagement

Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) across the country are playing a dangerous game with public engagement—one where they keep changing the rules and moving the goalposts. From inadequate notice periods to last-minute document releases, these boards are creating barriers that echo troubling federal trends, effectively sidelining the very people who have the most at stake: patients.

These state-level games mirror concerning federal developments, most notably the rescinding of the Richardson Waiver by U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. This action removed a 50-year precedent requiring public input on HHS rules—effectively telling patients and advocates their opinions aren't welcome at the policy table.

As these transparency rollbacks continue, people who rely on medications face increasing uncertainty about their access to life-sustaining treatments—while boards claim to represent their interests through processes that actively exclude them.

Maryland PDAB: How to Follow the Letter of the Law While Breaking Its Spirit

Maryland's Prescription Drug Affordability Board offers a master class in technical compliance that functionally blocks meaningful public participation. Their recent meeting preparation tactics exemplify how these boards can check procedural boxes while effectively sidelining patient voices.

On March 18, 2025, the Maryland PDAB posted a revised agenda for their upcoming March 24 meeting. This might seem unremarkable until you realize the public comment deadline was March 19—giving stakeholders exactly one day to review, analyze, and formulate responses to complex pharmaceutical policy documents. The revised agenda wasn't a minor update either. It contained material differences from the previous version, including a comprehensive cost review dossier for Farxiga, a medication critical for many people with diabetes and heart failure.

As CANN's letter to the board noted, "Posting the updated agenda with associated meeting materials the day before the deadline for comment is not a good faith effort in garnering public trust, nor does it display value in public input." The Maryland PDAB's approach creates a veneer of public engagement while practically guaranteeing that meaningful input will be minimal.

This pattern suggests the board views public comment as a procedural hurdle rather than a valuable source of insight. By technically fulfilling their obligation to post materials before the comment deadline (even if by mere hours), they've found a convenient loophole that undermines the very transparency standards that public notice requirements are designed to uphold.

The Maryland case isn't an anomaly. It's a symptom of a growing tendency to treat public engagement as an inconvenient formality rather than a crucial component of sound healthcare policy development.

The Federal Parallel: HHS and the Richardson Waiver

The state-level PDAB maneuvers don't exist in a vacuum. They mirror a troubling federal precedent set by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who recently rescinded the Richardson Waiver—a decision that effectively slams the door on patient advocacy at the federal level.

The Richardson Waiver has a 50-year history. Established in 1971, it required HHS to subject matters relating to "public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts" to the American Procedures Act's notice and comment rulemaking guidelines. This waiver was created specifically to ensure public voices would be heard on matters that directly affect their health and well-being.

Now, that protection is gone. The new HHS rule claims the waiver "impose[s] costs on the Department and the public, are contrary to the efficient operation of the Department, and impede the Department's flexibility to adapt quickly to legal and policy mandates." This bureaucratic language translates to a simple message: we don't care what you think.

God forbid they remember who they work for.

And the impact is far-reaching. While Medicare remains protected under separate provisions of the Medicare Act, critical programs like Medicaid, SAMHSA, and the Administration for Children and Families now operate without mandated public comment periods. Legal experts note this could allow for swift implementation of controversial measures like Medicaid work requirements without going through normal rulemaking processes.

The timing is particularly ironic given the Office of Management and Budget's recent guidance letter emphasizing the importance of "broadening public participation and community engagement" and making it "easier for the American people to share their knowledge, needs, ideas, and lived experiences to improve how government works for and with them."

This federal retreat from transparency sets a dangerous tone that state-level boards appear eager to follow.

Other State PDAB Examples: Oregon and Colorado's Concerning Patterns

Maryland isn't alone in its questionable approach to public engagement. Oregon's PDAB recently decided to include Odefsey—an antiretroviral medication for people living with HIV—on its list for cost control exploration, contradicting previous discussions to protect these medications. While they claim they might reconsider based on affordability research, this flip-flop creates unnecessary anxiety for people who depend on these treatments.

Colorado's PDAB situation is particularly egregious. Since 2023, CANN has repeatedly requested that the board consult with the state health department about rebate impacts on public health infrastructure and patient affordability—concerns echoed by the former SDAP director and PDAB members themselves.

Yet Colorado PDAB staff have consistently avoided conducting a proper fiscal impact analysis, bluntly stating "We won't be doing that" when asked directly. This refusal persisted even as formal rulemaking began, which triggers statutory requirements for analyses under Colorado's Administrative Procedure Act.

The board has repeatedly postponed its first rulemaking hearing, effectively delaying compliance with transparency requirements. Meanwhile, the Joint Budget Committee has begun questioning the PDAB's financial accountability, receiving only partial responses about consultant costs and litigation expenses.

Most concerning is the disconnect between PDAB actions and demonstrated patient benefits. A 2024 analysis of Oregon's similar program showed states would need additional funds to maintain programs under an upper payment limit system—with no meaningful patient affordability improvements identified.

Patient Impact: Why This Matters

Behind the procedural games and policy maneuvers are real people whose lives hang in the balance. The Colorado PDAB's actions exemplify how these bureaucratic decisions create genuine fear and uncertainty for people with rare diseases and conditions requiring specialized medications.

Twelve-year-old Avery Kluck lives with Aicardi syndrome and faces life-threatening seizures that have been intensifying. Her doctors recommended Sabril, a powerful anticonvulsant costing up to $10,000 per month—a medication on Colorado's PDAB radar for potential price controls.

"We're to a point now where her seizures are getting more violent, and this is our last resort," explains Heather Kluck, Avery's mother. "And now I'm finding out she may not have access to it." The family faces an impossible choice between starting a medication that might become unavailable or watching their daughter suffer.

This uncertainty isn't theoretical. At least one pharmaceutical company has already threatened to pull drugs from Colorado if price caps are imposed. For medications like Sabril, which are dangerous to discontinue abruptly, such market exits could be catastrophic.

People living with cystic fibrosis also had to mobilize to prevent Colorado's PDAB from declaring Trikafta "unaffordable," with one parent describing the experience as "torturous for our family" and another stating: "It's an experiment, and it's really gross that they're doing it on people who are really sick."

The irony is painful: boards created to increase medication access may end up restricting it for those who need it most.

Conclusion

These boards, created under the guise of helping patients afford medications, are operating in ways that actively silence patient voices. From Maryland's last-minute document dumps to Colorado's refusal to conduct impact analyses and Oregon's policy reversals on critical medications, these boards are erecting barriers that exclude the very people who will bear the consequences of their decisions.

The problems run deeper than procedural failures. The fundamental approach of PDABs—attempting to control drug prices without adequately assessing impacts on patient access—risks creating catastrophic unintended consequences for people who depend on specialized medications. Avery Kluck and others living with rare conditions don't have the luxury of waiting while boards experiment with price controls that might make their life-saving treatments unavailable.

The pattern is clear: from the federal level with RFK Jr.'s dismantling of public comment protections to state PDABs playing administrative games, we're witnessing a coordinated retreat from meaningful public engagement in healthcare policy. This isn't just bad governance—it's dangerous for patients.

States should seriously reconsider whether PDABs serve any legitimate purpose beyond political theater. At minimum, stakeholders across the healthcare spectrum must demand that these boards either implement truly transparent, patient-centered processes or acknowledge they cannot fulfill their stated mission without causing harm to the very people they claim to help.

Flying Blind: Public Health Without Population Data

On January 31, 2025, federal health agencies began removing thousands of webpages and datasets from public access in response to executive orders from the Trump Administration targeting "gender ideology" and diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. By February 1, over 8,000 federal webpages and 450 government domains had gone dark, including critical public health resources from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Immunologist and microbiologist Dr. Andrea Love, Executive Director of the American Lyme Disease Foundation, minced no words regarding the executive actions: "If you weren't clear: a President ordering a Federal health and disease agency to delete pages on its website is a public health crisis." The scope of removed content spans decades of population health data, from the 40-year-old Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System to current HIV surveillance statistics. Many pages that have returned now display banners warning of further modifications, creating uncertainty around the future availability and integrity of federal health data.

This sudden removal of public health information echoes similar challenges faced during the early COVID-19 response, when limited access to comprehensive population data hampered the ability to identify and address emerging health disparities. As we examine the current situation, the key question becomes: How can evidence-based public health function without access to the very data that drives decision-making and ensures equitable health outcomes?

Scale of Impact

The removal of federal health datasets represents an unprecedented disruption to public health surveillance and research capabilities. According to KFF analysis, key resources taken offline include:

The CDC's Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, which for 40 years has tracked critical health indicators among high school students. This dataset has been instrumental in identifying emerging health crises, including the rise in youth mental health challenges and substance use patterns.

CDC's AtlasPlus tool, containing nearly 20 years of surveillance data for HIV, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis, is no longer accessible. This platform has been essential for tracking disease trends and designing targeted prevention strategies.

The Social Vulnerability Index and Environmental Justice Index - critical tools for identifying communities at heightened risk during public health emergencies and environmental disasters - have also been removed. These resources help public health officials allocate resources effectively during crises and natural disasters.

Public health researchers report that the loss of demographic data collection and analysis capabilities particularly impacts their ability to identify and address health disparities.

As Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health notes, "Health equity is basically all of public health."

The ability to analyze health outcomes across different populations is fundamental to developing effective interventions and ensuring equitable access to care.

The CDC's healthcare provider resources have also been affected, including treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infections and HIV prevention protocols. This loss of clinical guidance materials creates immediate challenges for healthcare providers working to deliver evidence-based care.

Beyond individual datasets, this wholesale removal of public health information disrupts the interconnected nature of federal health data systems. Many of these resources inform each other, creating compounding effects when multiple datasets become unavailable simultaneously.

Research and Care Delivery Impact

The removal of federal health data creates immediate challenges for both research and clinical care delivery. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) warned that removing HIV and LGBTQ+ related resources from CDC websites "creates a dangerous gap in scientific information and data to monitor and respond to disease outbreaks."

This impact is particularly acute in STI prevention and treatment. Including gender and demographic data in research helps identify populations at elevated risk for infections like syphilis, which has reached its highest levels in 50 years. Without this data, developing targeted interventions becomes significantly more challenging.

For HIV prevention specifically, the loss of CDC's AtlasPlus tool removes access to critical surveillance data that guides prevention and treatment strategies. Healthcare providers report that missing CDC clinical guidance on HIV testing and PrEP prescribing creates uncertainty in delivering evidence-based care.

David Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors, emphasizes the immediate clinical impact: "Doctors in every community in America rely on the STI treatment guidelines to know what tests to run, to know what antibiotic will work on which infection, and how to avoid worsening antibiotic resistance. These are the guidelines for treating congenital syphilis, for preventing HIV from spreading, and for keeping regular people healthy every time they go to the doctor."

The loss of demographic data collection capabilities also threatens to undermine decades of progress in understanding and addressing health disparities. Research requiring analysis of health outcomes across different populations may face delays or compromised results without access to comprehensive federal datasets.

This disruption extends beyond immediate clinical care to impact long-term research projects and clinical trials. FDA guidance documents about ensuring diverse representation in clinical studies are no longer accessible, potentially affecting the development of new treatments and their applicability across different populations.

Historical Context and Implications

The current removal of federal health data follows concerning precedent. During the COVID-19 pandemic, similar actions to restrict access to public health data hampered effective response. In July 2020, hospital COVID-19 data reporting was moved from CDC control to a private contractor, leading to significant gaps in data access and accuracy that impeded pandemic response.

As Harvard epidemiologist Nancy Krieger notes, "There's been a history in this country recently of trying to make data disappear, as if that makes problems disappear... But the problems don't disappear, and the suffering gets worse."

This observation proved accurate during COVID-19, when limited access to comprehensive demographic data delayed recognition of disparate impacts on communities of color.

Early COVID-19 response efforts were hampered by insufficient data about how the virus affected different populations. This information gap contributed to delayed identification of emerging hotspots and slowed targeted intervention efforts. The result was preventable disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, particularly among Black, Hispanic, and Native American communities.

Today's wholesale removal of federal health data risks recreating similar blind spots across multiple public health challenges. Without demographic data to identify disparities and guide interventions, public health officials lose the ability to effectively target resources and measure outcomes. As Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo emphasizes, this data is "really important for us to answer the essential question of public health, which is, Who is being affected and how do we best target our limited resources?"

Legal Response and Policy Challenges

On February 4, 2025, Doctors for America filed suit against multiple federal agencies including the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The lawsuit challenges two key actions: OPM's directive requiring agencies to remove webpages and datasets, and the subsequent removal of critical health information by CDC, FDA, and HHS. The complaint argues these actions violated both the Administrative Procedure Act and the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 (PRA).

Under the PRA, federal agencies must "ensure that the public has timely and equitable access to the agency's public information" and "provide adequate notice when initiating, substantially modifying, or terminating significant information dissemination products." The complaint alleges agencies failed to provide required notice before removing vital health information and datasets.

The legal challenge emphasizes the fundamental role these datasets play in public health. According to the filing, "The removal of the webpages and datasets creates a dangerous gap in the scientific data available to monitor and respond to disease outbreaks, deprives physicians of resources that guide clinical practice, and takes away key resources for communicating and engaging with patients."

Nine out of twelve public health researchers on CDC's advisory board signed a letter to the agency's acting director seeking explanation for the data removal. These scientists expect to face consequences for speaking out but emphasize the critical nature of maintaining public access to health data.

Data Preservation Efforts

As federal health datasets disappeared, researchers and institutions launched rapid preservation efforts. Harvard University organized its first "datathon" to archive website content through the Wayback Machine, while other academic institutions worked to preserve datasets locally.

The Kaiser Family Foundation reports having downloaded significant portions of CDC data prior to removal. While some CDC data files have been restored, they currently lack essential documentation like questionnaires and codebooks needed for analysis.

For healthcare providers needing immediate access to clinical guidelines, medical associations are working to provide archived copies of treatment protocols. The Infectious Disease Society of America and HIV Medicine Association are coordinating with members to ensure continued access to critical clinical resources.

State health departments maintain some parallel data collection systems that may help fill gaps in federal surveillance. However, these systems often rely on federal frameworks for standardization and analysis, potentially limiting their utility as standalone resources.

These preservation efforts, while necessary, cannot fully replace the coordinated federal data infrastructure needed for comprehensive public health surveillance and research.

Recommendations

Healthcare providers and public health officials should consider these immediate steps to ensure continued access to vital health information:

Data Access and Preservation

Download and securely store copies of restored CDC datasets, including documentation

Maintain offline copies of current clinical guidelines and protocols

Establish relationships with academic institutions archiving federal health data

Alternative Data Sources

Connect with state and local health departments to access regional surveillance data

Utilize medical society and professional organization resources for clinical guidance

Consider participating in alternative data collection networks being established by research institutions

Advocacy Actions

Support ongoing legal efforts to restore data access

Document specific impacts of data loss on care delivery and research

Engage with professional organizations coordinating preservation efforts

Future Planning

Develop contingency plans for maintaining essential health surveillance

Build redundant data collection systems where feasible

Strengthen partnerships with academic and nonprofit research organizations

These steps cannot fully replace federal health data infrastructure but may help maintain critical public health functions while broader access issues are resolved.

When Algorithms Deny Care: The Insurance Industry's AI War Against Patients

The assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December 2024 laid bare a healthcare crisis where insurance companies use artificial intelligence to systematically deny care while posting record profits. Federal data shows UnitedHealthcare, which covers 49 million Americans, denied nearly one-third of all in-network claims in 2022 - the highest rate among major insurers.

This reflects an industry-wide strategy that insurance scholar Jay Feinman calls "delay, deny, defend" - now supercharged by AI. These systems automatically deny claims, delay payment, and force sick people to defend their right to care through complex appeals. A Commonwealth Fund survey found 45% of working-age adults with insurance faced denied coverage for services they believed should be covered.

The consequences are devastating. As documented cases show, these automated denial systems routinely override physician recommendations for essential care, creating a system where algorithms, not doctors, decide who receives treatment. For those who do appeal, insurers approve at least some form of care about half the time. This creates a perverse incentive structure where insurers can deny claims broadly, knowing most people will not fight back. For the people trapped in this system, the stakes could not be higher - this is quite literally a matter of life and death.

The Rise of AI in Claims Processing

Health insurers have increasingly turned to AI systems to automate claims processing and denials, fundamentally changing how coverage decisions are made. A ProPublica investigation revealed that Cigna's PXDX system allows its doctors to deny claims without reviewing patient files, processing roughly 300,000 denials in just two months. "We literally click and submit. It takes all of 1.2 seconds to do 50 at a time," a former Cigna doctor reported.

The scope of automated denials extends beyond Cigna. UnitedHealth Group's NaviHealth uses an AI tool called "nH Predict" to determine length-of-stay recommendations for people in rehabilitation facilities. According to STAT News, this system generates precise predictions about recovery timelines and discharge dates without accounting for people's individual circumstances or their doctors' medical judgment. While NaviHealth claims its algorithm is merely a "guide" for discharge planning, its marketing materials boast about "significantly reducing costs specific to unnecessary care."

Only about 1% of denied claims are appealed, despite high rates of denials being overturned when challenged. This creates a system where insurers can use AI to broadly deny claims, knowing most people will not contest the decisions. The practice raises serious ethical concerns about algorithmic decision-making in healthcare, especially when such systems prioritize cost savings over medical necessity and doctor recommendations.

Impact on Patient Care

The human cost of AI-driven claim denials reveals a systemic strategy of "delay, deny, defend" that puts profits over patients. STAT News reports the case of Frances Walter, an 85-year-old with a shattered shoulder and pain medication allergies, whose story exemplifies the cruel efficiency of algorithmic denial systems. NaviHealth's algorithm predicted she would recover in 16.6 days, prompting her insurer to cut off payment despite medical notes showing she could not dress herself, use the bathroom independently, or operate a walker. She was forced to spend her life savings and enroll in Medicaid to continue necessary rehabilitation.

Walter's case is not unique. Despite her medical team's objections, UnitedHealthcare terminated her coverage based solely on an algorithm's prediction. Her appeal was denied twice, and when she finally received an administrative hearing, UnitedHealthcare didn't even send a representative - yet the judge still sided with the company. Walter's case reveals how the system is stacked against patients: insurers can deny care with a keystroke, forcing people to navigate a complex appeals process while their health deteriorates.

The fundamental doctor-patient relationship is being undermined as healthcare facilities face increasing pressure to align their treatment recommendations with algorithmic predictions. The Commonwealth Fund found that 60% of people who face denials experience delayed care, with half reporting their health problems worsened while waiting for insurance approval. Behind each statistic are countless stories like Walter's - people suffering while fighting faceless algorithms for their right to medical care.

The AI Arms Race in Healthcare Claims

Healthcare providers are fighting back against automated denials by deploying their own AI tools. New startups like Claimable and FightHealthInsurance.com help patients and providers challenge insurer denials, with Claimable achieving an 85% success rate in overturning denials. Care New England reduced authorization-related denials by 55% using AI assistance.

While these counter-measures show promise, they highlight a perverse reality: healthcare providers must now divert critical resources away from patient care to wage algorithmic warfare against insurance companies. The Mayo Clinic has cut 30 full-time positions and spent $700,000 on AI tools simply to fight denials. As Dr. Robert Wachter of UCSF notes, "You have automatic conflict. Their AI will deny our AI, and we'll go back and forth."

This technological arms race exemplifies how far the American healthcare system has strayed from its purpose. Instead of focusing on patient care, providers must invest millions in AI tools to combat insurers' automated denial systems - resources that could be spent on direct patient care, medical research, or improving healthcare delivery. The emergence of these counter-measures, while potentially helpful for providers and patients seeking care, highlights fundamental flaws in our healthcare system that require policy solutions, not just technological fixes.

AI Bias: Amplifying Healthcare Inequities

The potential for AI systems to perpetuate and intensify existing healthcare disparities is deeply concerning. A comprehensive JAMA Network Open study examining insurance claim denials revealed that at-risk populations experience significantly higher denial rates.

The research found:

Low-income patients had 43% higher odds of claim denials compared to high-income patients

Patients with high school education or less experienced denial rates of 1.79%, versus 1.14% for college-educated patients

Racial and ethnic minorities faced disproportionate denial rates:

Asian patients: 2.72% denial rate

Hispanic patients: 2.44% denial rate

Non-Hispanic Black patients: 2.04% denial rate

Non-Hispanic White patients: 1.13% denial rate

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Consumer Representatives report warns that AI tools, often trained on historically biased datasets, can "exacerbate existing bias and discrimination, particularly for marginalized and disenfranchised communities."

These systemic biases stem from persistent underrepresentation in clinical research datasets, which means AI algorithms learn and perpetuate historical inequities. The result is a feedback loop where technological "efficiency" becomes a mechanism for deepening healthcare disparities.

Legislative Response and Regulatory Oversight

While California's Physicians Make Decisions Act and new Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) rules represent progress in regulating AI in healthcare claims, the NAIC warns that current oversight remains inadequate. California's law prohibits insurers from using AI algorithms as the sole basis for denying medically necessary claims and establishes strict processing deadlines: five business days for standard cases, 72 hours for urgent cases, and 30 days for retrospective reviews.

At the federal level, CMS now requires Medicare Advantage plans to base coverage decisions on individual circumstances rather than algorithmic predictions. As of January 2024, coverage denials must be reviewed by physicians with relevant expertise, and plans must follow original Medicare coverage criteria. CMS Deputy Administrator Meena Seshamani promises audits and enforcement actions, including civil penalties and enrollment suspensions for non-compliance.

The insurance industry opposes these safeguards. UnitedHealthcare's Medicare CEO Tim Noel argues that restricting "utilization management tools would markedly deviate from Congress' intent." But as the NAIC emphasizes, meaningful transparency requires more than superficial disclosures - insurers must document and justify their AI systems' decision-making criteria, training data, and potential biases. Most critically, human clinicians with relevant expertise must maintain true decision-making authority, not just rubber-stamp algorithmic recommendations.

Recommendations for Action

The NAIC framework provides a roadmap for protecting patients while ensuring appropriate oversight of AI in healthcare claims. Key priorities for federal and state regulators:

Require comprehensive disclosure of AI systems' training data, decision criteria, and known limitations

Mandate documentation of physician recommendation overrides with clinical justification

Implement regular independent audits focused on denial patterns affecting marginalized communities

Establish clear accountability and substantial penalties when AI denials cause patient harm

Create expedited appeal processes for urgent care needs

Healthcare providers should:

Document all cases where AI denials conflict with clinical judgment

Track patient impacts from inappropriate denials, including worsened health outcomes

Report systematic discrimination in algorithmic denials

Support patient appeals with detailed clinical documentation

Share denial pattern data with regulators and policymakers

The solutions cannot rely solely on technological counter-measures. As the NAIC emphasizes, "The time to act is now."

Conclusion

The AI-driven denial of care represents more than a technological problem - it's a fundamental breach of the healthcare system's ethical foundations. By prioritizing algorithmic efficiency over human medical judgment, insurers have transformed life-saving care into a battlefield where profit algorithms determine patient survival.

Meaningful change requires a multi-pronged approach: robust regulatory oversight, technological accountability, and a recommitment to patient-centered care. We cannot allow artificial intelligence to become an instrument of systemic denial, transforming healthcare from a human right into an algorithmic privilege.

Patients, providers, and policymakers must unite to demand transparency, challenge discriminatory systems, and restore the primacy of human medical expertise. The stakes are too high to accept a future where lines of code determine who receives care and who is left behind. Our healthcare system must be rebuilt around a simple, non-negotiable principle: medical decisions should serve patients, not corporate balance sheets.

Biden’s Inaction Leaves Copay Assistance in Limbo

Inflated prescription drug costs in the United States continue to place a significant burden on people living with chronic conditions. Copay assistance programs, designed to help people afford their medications, have become essential. Yet recent policy decisions and industry practices have put these programs at risk, potentially jeopardizing access to necessary treatments.

The Biden Administration's recently proposed 2026 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters (NBPP) rule omits crucial regulations that patient advocates have long been demanding. This inaction allows insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to continue profiting from billions of dollars of drug manufacturer copay assistance intended for patients.

The State of Copay Assistance

Copay assistance programs, primarily offered by pharmaceutical manufacturers, provide financial support to help cover out-of-pocket costs for prescription medications. As health insurance plans increasingly shift costs to patients through higher deductibles and copayments, these programs have become crucial.

According to the latest data from The IQVIA Institute, manufacturer copay assistance offset patient costs by $23 billion in 2023, a $5 billion increase from the previous year. This figure represents 25% of what retail prescription costs would have been without such assistance. Over the past five years, copay assistance has totaled $84 billion, highlighting its importance in maintaining access to medications.

Despite the significance of copay assistance, copay accumulator and maximizer programs accounted for $4.8 billion of copay assistance in 2023—more than double the amount in 2019. Implemented primarily by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and insurers, these programs prevent assistance from counting towards patients' deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums. This practice effectively nullifies the intended benefit of copay assistance, leaving people to face unexpected and often unaffordable costs later in the year.

Recent scrutiny of PBMs has brought attention to these practices. As discussed in our recent article on PBMs, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has filed a lawsuit against the largest PBMs for alleged anticompetitive practices that inflate drug costs and limit access to medications. These developments underscore concerns about how PBM practices, including the implementation of copay accumulator programs, impact medication affordability and access.

The impact on access is serious. IQVIA reports that in 2023, patients abandoned 98 million new therapy prescriptions at pharmacies, with abandonment rates rising as out-of-pocket costs increase. This trend highlights the critical role copay assistance plays in helping people not only initiate but also maintain their prescribed treatments.

Public opinion strongly supports action on this issue. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 80% of adults believe prescription drug costs are unreasonable, with broad support for various policy proposals to lower drug costs. This sentiment reflects the public's recognition of the financial challenges faced in accessing necessary medications.

The Legal and Regulatory Landscape

The regulatory environment surrounding copay assistance programs has been in flux, with significant developments in recent years. On September 29, 2023, a federal court struck down a rule that allowed insurers to decide whether copay assistance would count towards patients' out-of-pocket maximums. This ruling reinstated the 2020 NBPP rule, which required insurers to count copay assistance towards patient cost-sharing, except for brand-name drugs with available generic equivalents.

Despite this, the federal government declared that it would not enforce the court's decision or the 2020 NBPP rule until new regulations are issued. This inaction has left patients facing continued uncertainty about the status of their copay assistance.

On January 16, 2024, the Biden Administration dropped its appeal of the court decision. While this action confirms that the 2020 NBPP rule will generally apply until new rules are issued, the lack of enforcement leaves plans and insurers in a gray area regarding their copay accumulator programs.

At the state level, there has been a growing movement to address copay accumulator programs. As of 2024, 21 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have enacted laws addressing the use of these programs by insurers or PBMs. These laws generally require any payments made by or on behalf of the patient to be applied to their annual out-of-pocket cost-sharing requirement. While these state actions provide important protections, they do not cover all insurance plans, particularly those regulated at the federal level.

The 2026 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters Proposal

The proposed 2026 NBPP rule, released by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), has drawn criticism from patient advocacy groups for significant omissions related to copay assistance and essential health benefits (EHB).

Notably absent from the proposed rule are regulations clarifying whether copay assistance will count toward patient cost-sharing. This omission perpetuates uncertainty created by previous conflicting rules and court decisions, allowing insurers and PBMs to continue implementing copay accumulator programs that can leave people with unexpected and unaffordable out-of-pocket costs.

The proposal also fails to include a provision to ensure that all drugs covered by large group and self-funded plans are considered essential health benefits, despite previous indications that such a provision would be forthcoming. This failure to close the EHB loophole allows employers, in collaboration with PBMs and third-party vendors, to designate certain covered drugs as "non-essential," circumventing Affordable Care Act (ACA) cost-sharing limits designed to protect people from excessive expenses.

By exploiting this loophole, plan sponsors can collect copay assistance provided by manufacturers without applying it to beneficiaries' cost-sharing requirements. This practice effectively doubles the financial burden on patients: first, by accepting the copay assistance, and second, by requiring them to pay their full out-of-pocket costs as if no assistance had been provided.

Recent research by the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute has revealed that over 150 employers and insurers are taking advantage of the EHB loophole. This list includes:

Major companies such as Chevron, Citibank, Home Depot, Target, and United Airlines

Universities including Harvard, Yale, and New York University

Unions like the New York Teamsters and the Screen Actors Guild

States such as Connecticut and Delaware

Insurers, including several Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans

Patient advocacy groups have reacted strongly to these omissions. Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute, stated, "Every day these rules are delayed is another day that insurers and PBMs are pocketing billions of dollars meant for patients who are struggling to afford their drugs." This sentiment reflects the frustration of many who have long advocated for stronger protections.

The widespread exploitation of the EHB loophole underscores the urgent need for federal action to protect patients from these practices. The failure to address these critical issues in the 2026 NBPP proposed rule highlights a significant setback in efforts to improve medication affordability and access for people living with chronic conditions.

The Impact on Patients: Data and Experiences

The real-world impact of copay accumulator programs and the EHB loophole is reflected in both data and personal experiences. IQVIA reports that patient out-of-pocket costs reached $91 billion in 2023, an increase of $5 billion from the previous year. This rise in costs comes despite the $23 billion in copay assistance provided by manufacturers, highlighting the growing financial burden on patients.

Prescription abandonment is particularly concerning. Patients abandoned 98 million new therapy prescriptions at pharmacies in 2023, with abandonment rates increasing as out-of-pocket costs rise. More than half of new prescriptions for novel medicines go unfilled, and only 31% of patients remained on therapy for a year. These statistics highlight the direct link between cost and medication adherence.

People across the country are facing these challenges. For example, a mother whose daughter lives with cystic fibrosis shared her experience with a copay accumulator program. In early 2019, her family's out-of-pocket cost for her daughter's medication suddenly jumped from $30 to $3,500 per month when their insurance plan stopped applying copay assistance to their deductible. This unexpected change forced the family to put the cost on credit cards, creating significant financial strain and unnecessary medical debt.

Similarly, a person living with psoriasis faced steep increases in medication costs when their insurance company stopped counting copay assistance towards their deductible. The copay rose from $35 to $1,250 monthly, leaving them with only $26 from their disability payment after covering the copay.

These stories are not isolated incidents. People living with conditions such as HIV, hepatitis, multiple sclerosis, and hemophilia are facing similar challenges. The impact extends beyond financial stress, affecting medication adherence and, ultimately, health outcomes. For many, the choice becomes one between essential medications and other basic needs such as food and shelter—a decision no one should have to make.

Policy Recommendations and Advocacy Efforts

Patient advocacy groups are intensifying efforts for policy changes at both the federal and state levels. The All Copays Count Coalition, comprising over 80 organizations representing people living with serious and chronic illnesses, has been at the forefront of these efforts. In a letter to federal officials, the coalition urged for a revision of the cost-sharing rule to include clear protections ensuring that copayments made by or on behalf of a patient are counted towards their annual cost-sharing contributions. Specific recommendations include:

Maintaining the protections included in the 2020 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters.

Ensuring that copay assistance counts for medically appropriate medications, even when generic alternatives are available.

Limiting Health Savings Account-High Deductible Health Plan (HSA-HDHP) carve-outs to situations where using copay assistance would result in HSA ineligibility.

At the state level, advocacy efforts have led to the passage of laws restricting copay accumulator programs in 20 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico as of summer 2023. However, these state-level protections do not cover all insurance plans, particularly those regulated at the federal level, highlighting the need for comprehensive federal action.

Advocates are calling for:

Immediate enforcement of the 2020 NBPP rule, requiring insurers to count copay assistance towards patient cost-sharing in most cases.

Swift action to close the essential health benefits loophole for all plans, including large group and self-funded plans.

Increased oversight and regulation of PBM practices, particularly regarding copay accumulator and maximizer programs.

Passage of comprehensive federal legislation to protect those relying on copay assistance.

As Carl Schmid emphasized, "While they have gone on record that they will issue these rules, the clock is ticking and there isn't much time left." This reflects the growing frustration among patient advocates with the administration's delays in addressing these issues.

Policymakers must act swiftly to close the essential health benefits loophole and ensure that all copay assistance counts towards patients' out-of-pocket costs. Stakeholders across the healthcare ecosystem—from insurers and PBMs to pharmaceutical companies and patient advocacy groups—must collaborate to develop solutions that prioritize access and affordability. The health and well-being of millions depend on these critical policy changes.

Are Cancer Risks Higher for People Living with HIV/AIDS

For many years, scientists have been exploring the relationship between HIV/AIDS and various cancers. This complex connection stems from how the virus weakens the immune system, leaving folks more vulnerable. While there has been evidence of higher prevalence of certain cancers amongst people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), the actual mechanisms have thus far remained unclear.

Recently, a team from Hospital 12 de Octubre (H12O) and the National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain found that Hepatitis B and C viral infections can cause multiple myeloma and its pathological precursors, monoclonal gammopathies. Additionally, they found that early detection of viral hepatitis and the use of antiretrovirals resulted in better health outcomes in general – taking care of the hepatitis and the monoclonal gammopathies/multiple myeloma at the same time.

This groundbreaking discovery comes shortly after the data was made available from the HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study, which links United States’ HIV surveillance and cancer registry data from 2000 to 2019. Haas et al. examined this data and created a population-based linkage study which garnered the largest cohort to date for estimating anal cancer among PLWHA in the United States, with a cohort of 3,444 anal cancers diagnosed in patients with HIV. Of these 3,444 cases, 2,678 occurred in patients with a prior AIDS diagnosis.

Additionally, several cancers have been identified as AIDS-defining illnesses. The presence of these conditions indicates that the patient has reached the advanced stage of HIV infection known as AIDS. These include invasive cervical cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and some iterations of lymphoma (e.g. diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt or Burkitt-like lymphoma). A 2021 meta-analysis of twenty-four studies found that women with HIV are six times more likely to have cervical cancer than their counterparts without HIV. This is likely due to the inability to clear human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, which can cause cervical cell changes if left untreated in some cases. According to Lymphoma Action, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is around fifteen times more common in PLWHA, while PLWHA are around 30 times more likely to develop Burkitt lymphoma.

As is often the case when living with HIV/AIDS and co-occurring conditions, early detection, open and frequent communication with healthcare providers, and HIV/AIDS treatment regimen adherence can make a significant difference in the duration and intensity of these conditions, so patients should be encouraged to be vigilant self-advocates when it comes to their health and wellness, and, when needed, identify resources among caregivers and community who might be able to assist in care advocacy.

Eddie Hamilton (left), Bill Arnold (right)

CANN would like to recognize the fierce advocacy of our colleague, friend, and former board member, Edward “Eddie” Hamilton (pictured). Eddie served on CANN’s Board of Directors from 2014 to 2022 and was the Founder and Executive Director of the ADAP Educational Initiative, which assisted clients enrolled under the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP). In 2012, Eddie was honored as the ADAP Champion of the Year by ADAP Advocacy for fighting the Ohio Department of Health’s attempts to implement medical eligibility criteria to qualify for ADAP services. Eddie passed away on July 12, 2022, having had cancer twice. CANN continues to honor Eddie’s legacy as well as that of the late Bill Arnold (pictured right), who served as CANN’s founding President & CEO, by championing patient-centric action toward health equity and access.

Profit Over Patients: Challenging the Understaffing Crisis in Healthcare

On December 31, 2023 former U.S. Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson suffered and died in a completely preventable yet entirely foreseeable tragedy. Rep. Johnson, a dedicated nurse and a fervent advocate for equitable healthcare, succumbed to an infection contracted in a rehabilitation facility, a direct consequence of medical neglect. This incident is a glaring example of the systemic issues plaguing our healthcare institutions, where intentional understaffing and profit-driven motives often come at the expense of patient care and staff well-being. Her experience tragically highlights the broader systemic issues in healthcare, including rampant understaffing and the consequences of healthcare system consolidation.

The Tragic Circumstances of Rep. Johnson's Passing

According to a Texas Tribune report, Rep. Johnson died a “terrible, painful death” from an infection caused by negligence at her Dallas recovery facility following back surgery. The infection was a result of being left to lie in her own feces and urine for roughly an hour while she repeatedly called for help that didn’t come. The facility reportedly told family that all staff were unavailable as she called for help due to being in a training. Her son, Kirk Johnson, minced no words as he stated, "She was screaming out in pain, asking for help. If she had gotten the proper care, she would be here today.”

The family notified Baylor Scott & White Health System and Baylor Scott & White Institute for Rehabilitation of their intention to sue on the grounds of medical negligence. The lawsuit, if not settled, will highlight the deadly consequences of inadequate patient care in healthcare facilities. This legal battle is complicated by Texas law, which limits medical malpractice lawsuit awards to $250,000. Such legislative decisions, influenced by powerful hospital lobbies, not only restrict legal recourse for patients but also reflect deeper systemic issues in healthcare governance where institutional profits often overshadow patient rights.

The limitation on medical malpractice awards in Texas exemplifies a troubling trend in healthcare legislation. These laws, as detailed in a Miller & Zois report, often protect healthcare institutions at the expense of patient health and safety while significantly limiting patients' ability to seek fair compensation for medical negligence.

This legislative backdrop, coupled with intentional understaffing in healthcare facilities, creates a perilous situation where patient rights are limited and institutions are insulated from liability when their cost cutting measures cost lives. Maximizing profit and administrative and shareholder value by understaffing care facilities heightens the risk of medical errors, burns out staff, and creates unsafe working conditions. Yet, when these cost-cutting measures lead to harm, patients find their legal recourse severely restricted by malpractice caps while hospital staff burns out and are exposed to greater occupational hazards. The only ones not on the losing end are the hospitals and their executives.

Staffing Shortages or Healthcare Profiteering?

Across the country, as healthcare corporations report burgeoning profits, the reality within their healthcare facilities tells a story of compromised care and strained resources. Let’s take Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), the largest hospital system in the country, as an example. As reported in The Guardian, a study by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) highlights the disparities, revealing that staffing ratios at HCA Hospitals in 2020 were alarmingly 30% lower than national averages. Despite $7 billion in profits and $8 billion allocated to stock buybacks and paying out nearly $5 billion in dividends to shareholders, the investment in patient care, particularly in terms of staffing, remains inadequate.

The prevailing narrative of a nursing shortage in the United States is rigorously challenged by facts and voices from within the healthcare sector. National Nurses United (NNU) asserts that the core issue is not a lack of nurses but rather the widespread unwillingness of nurses to work under unsafe conditions. This perspective contradicts the healthcare industry's narrative and points to systemic issues in workforce management and underinvestment in medical staffing by hospital executives.

The intentional understaffing by healthcare facilities, as seen in cases like HCA Hospitals, is often driven by financial motivations. By keeping staffing levels low, these facilities aim to maximize profits, often at the expense of both patient care and staff well-being. This approach has led to a situation where the healthcare workforce is being pushed to its limits, leading to high turnover rates and a growing reluctance among nurses to work in such conditions.

The narrative of worker shortages is further complicated by the trend of healthcare system consolidation, which significantly reshapes healthcare markets, often at the expense of patient care and staff well-being. In May of 2023 The RAND Corporation gave testimony to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Health which underscored that consolidation frequently leads to higher healthcare costs without corresponding improvements in quality. Characterized by mergers and acquisitions across markets, this trend typically results in reduced competition, higher prices, and a focus on revenue generation over patient-centric values. Moreover, when private equity is involved, as highlighted by The British Medical Journal (BMJ), it often exacerbates patient harm.

The Human Cost of Cost-Cutting

Impact on Healthcare Workers: Nurses and other healthcare staff, the backbone of patient care, are stretched to their limits. A study by the University of Pennsylvania highlights the high levels of nurse burnout, a direct consequence of inadequate staffing. The study surveyed over 70,000 nurses and found that the chronic stress caused by high nurse-to-patient ratios significantly impacts their mental and physical health. The turnover rate in nursing, as reported by STAT News, is a testament to the unsustainable working conditions, with many nurses leaving the profession or seeking less demanding roles.