America's Vaccination Problem

Politics Trump Public Health

The United States is confronting a serious resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases, exemplified by the measles outbreak in Texas and New Mexico that has now infected over 124 people and claimed the life of an unvaccinated child. This crisis coincides with multiple failures in public health leadership and unprecedented political interference in evidence-based practice.

Recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analysis reveals that the percentage of children with a vaccine-hesitant parent varies dramatically by vaccine type — from 56% for COVID-19 vaccines to 12% for routine childhood vaccines. This growing hesitancy has created dangerous gaps in community protection across the country.

In a rapid succession of alarming developments within a single week, we've witnessed a new confirmed measles case in Kentucky from an international traveler, Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) Jr.'s cancellation of a multimillion-dollar project to develop an oral COVID-19 vaccine, and the FDA's abrupt cancellation of a critical advisory committee meeting on next season's flu vaccine formulation. During his first cabinet meeting appearance, Kennedy incorrectly stated there had been two measles deaths (there was one) and downplayed the outbreak as "not unusual" — a claim physicians immediately contradicted.

This confluence of declining vaccination rates, active disease outbreaks, and systematic dismantling of public health infrastructure represents a crisis entirely of our own making. It’s 2025 and children are dying from diseases we've known how to prevent for decades, not because of scientific limitations, but because of a collective failure to prioritize evidence over ideology.

A Dismantling in Real Time

At the February 27 cabinet meeting, HHS Secretary Kennedy made several troubling statements about the ongoing measles outbreak. "Measles outbreaks are not unusual," Kennedy claimed, an assertion quickly refuted by medical experts.

"Classifying it as 'not unusual' would be inaccurate," said Dr. Christina Johns, a pediatric emergency physician. "Usually an outbreak is in the order of a handful, not over 100 people that we have seen recently with this latest outbreak in West Texas."

Dr. Philip Huang, director of Dallas County Health and Human Services, was more direct: "This is not usual. Fortunately, it's not usual, and it's been because of the effectiveness of the vaccine."

Kennedy's statement that two people had died from measles was also incorrect – Texas officials confirmed there has been one death, an unvaccinated school-aged child. His claim that patients were hospitalized "mainly for quarantine" was astonishingly false. Local health officials reported that most patients required treatment for serious respiratory issues, including supplemental oxygen and IV fluids.

Meanwhile, in just his first two weeks in office, Kennedy has taken several actions that threaten to undermine vaccine development and public health guidance:

The FDA's Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) meeting scheduled for March was abruptly canceled. This annual meeting is crucial for selecting the strains to be included in next season's flu vaccines. A wise move in the middle of the worst flu season in 15 years. Norman Baylor, former director of the FDA's Office of Vaccine Research and Review, told NBC News: "I'm quite shocked. The VRBPAC is critical for making the decision on strain selection for the next influenza vaccine season."

Kennedy halted a $460 million contract with Vaxart to develop a new COVID-19 vaccine in pill form, just days before 10,000 people were scheduled to begin clinical trials.

Just days earlier, Kennedy indefinitely postponed a meeting of the CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which helps determine vaccine recommendations for states and insurers.

Dr. Paul Offit, a member of VRBPAC and vaccine expert at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, expressed his dismay: "I feel like the world is upside down. We aren't doing the things we need to do to protect ourselves."

Evidence of Vaccine Success Amid Political Attacks

In striking irony, the CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) just published new data demonstrating the remarkable success of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program in preventing cervical cancer. During 2008–2022, cervical precancer incidence decreased 79% among screened women aged 20–24 years, the age group most likely to have been vaccinated. Higher-grade precancer incidence decreased 80% in the same group.

This success story illustrates what effective vaccination programs can achieve when supported by consistent policy and healthcare provider recommendations. The HPV vaccine has prevented countless future cancers in a generation of young people, with similar potential for other vaccines when politics doesn't interfere with public health.

The contrast between this evidence of vaccine success and the current administration's assault on public health infrastructure could not be more glaring. At the very moment when scientific data confirms vaccines' life-saving impact, political appointees are systematically dismantling the systems designed to implement and monitor vaccination programs.

The False Promise of "Informed Consent"

Kennedy has justified halting vaccine promotion by claiming he wants future campaigns to focus on "informed consent" instead. However, experts warn this framing misrepresents the concept and creates dangerous misperceptions about vaccines (which, to be fair, would make it right in RFK Jr.’s wheelhouse—if only that were the actual job description).

Mark Navin, Lainie Friedman Ross, and Jason A. Wasserman explained in STAT News: "True 'informed consent' requires an understanding of how people process information about risks, and public health must promote collective benefits rather than focus entirely on individual autonomy."

Simply listing potential vaccine side effects without context creates predictable cognitive biases, similar to hearing about a shark attack and becoming afraid to swim despite the infinitesimal risk. As these experts note, "It is more like handing someone a list of everything that could go wrong on an airplane without mentioning that flying is far safer than driving."

The CDC's canceled 'Wild to Mild' campaign appropriately conveyed what matters most: vaccines' ability to turn severe, potentially deadly disease cases into manageable, mild illnesses—reducing hospitalizations, complications, and deaths. Replacing this messaging with uncontextualized risk information isn't enhancing informed consent — it's promoting fear and hesitancy.

The Expanding Measles Threat

Measles is making a dangerous comeback. The Kentucky Department of Health confirmed its first case since 2023 in an adult who recently traveled internationally. While contagious, the individual visited a Planet Fitness gym, potentially exposing others—a not-so-subtle reminder that wiping down equipment is more than just good manners.

This case adds to outbreaks in nine states, including Texas, New Mexico, Alaska, Georgia, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. The most severe remains in West Texas’ Gaines County, where nearly 14% of schoolchildren have religious exemptions from required vaccinations.

On February 26, an unvaccinated child in that Texas community became the first U.S. measles fatality since 2015 and the first pediatric death since 2003. Before vaccines, measles killed 400 to 500 Americans annually.

These outbreaks are particularly tragic given that the MMR vaccine is exceptionally safe and effective. Two doses provide 97% protection against a disease that, without vaccination, would infect nearly every child by age 15. Among 10,000 measles cases, 10 to 30 children will die, 2,000 will require hospitalization, and over 1,500 will suffer serious complications, some with lifelong consequences.

By contrast, severe vaccine side effects are extraordinarily rare—fewer than four in 10,000 people experience fever-related seizures, blood clotting issues, or allergic reactions. As beloved children’s author Roald Dahl wrote after losing his daughter Olivia to measles encephalitis in 1962: "I think it is almost a crime to allow your child to go unimmunized."

Roald Dahl and the open letter he wrote in 1986, encouraging parents to vaccinate their children against measles. (Credit: Ronald Dumont/Daily Express/Getty Images)

Declining Vaccination Rates

Vaccination rates for measles and other preventable diseases have been trending downward, creating dangerous gaps in community protection. According to research from the Center for American Progress, kindergarten MMR vaccination rates have fallen below the critical 95% threshold needed for herd immunity. Since the 2019-20 school year, coverage has dropped from 95% to approximately 93% nationwide, leaving over 250,000 children vulnerable to infection.

This decline is even more concerning at the state level. Thirty-nine states saw vaccination rates fall below the 95% threshold in the 2023-24 school year, an increase from 28 states during the 2019-20 school year. Overall, less than 93% of kindergarten children were up to date on their state-required vaccines in 2023-24, compared with 95% four years earlier.

COVID-19 and influenza vaccination rates show similar concerning trends. According to the CDC's vaccination tracking data, only 23.1% of adults have received the 2024-25 COVID vaccine, while 45.3% have received the seasonal flu vaccine. For adults 65 and older, these rates are somewhat higher but still insufficient – 44.4% for COVID and 70.2% for flu.

A 2022 modeling study estimated that over 9.1 million children (13.1%) in the United States are currently susceptible to measles infection. If pandemic-level vaccination declines persist without catch-up efforts, that number could rise to over 15 million children (21.7%), significantly increasing the risk of larger and more frequent outbreaks.

When Vaccines Become Political Identifiers

Vaccine-preventable diseases disproportionately impact vulnerable communities. Flu vaccination rates vary significantly by race, with 49% of White adults vaccinated, compared to 42% of Black adults and 35% of Hispanic adults. These disparities stem from access barriers, medical mistrust, and inconsistent provider recommendations.

The politicization of vaccines exacerbates these challenges. Support for school vaccine mandates has dropped from 82% in 2019 to 70% in 2023, driven by a sharp decline among Republicans (79% to 57%), while Democratic support remains stable at 85-88%. Similar trends appear among White evangelical Protestants, where support for school vaccine requirements fell from 77% to 58%. This geographic clustering of under-vaccinated populations fuels outbreaks—exactly what’s unfolding in West Texas.

Partisan divides extend beyond COVID-19. Republicans report lower annual flu vaccination rates than Democrats (41% vs. 56%), and among those fully vaccinated against COVID-19, Democrats are nearly three times as likely to have received a recent booster (32% vs. 12%). Vaccine hesitancy also correlates with education levels, further compounding risks in communities with both lower socioeconomic status and conservative political leanings.

Addressing these disparities requires public health strategies that acknowledge political polarization while working beyond it. Culturally tailored messaging, trusted community voices, and policies that eliminate access barriers are essential to counteract the social and ideological forces shaping vaccine decisions today.

State-Level Assaults: Louisiana's Ban on Vaccine Promotion

Federal attacks on vaccine policy are now playing out at the state level. In February 2025, the Louisiana Department of Health announced it would no longer promote mass vaccination through health fairs or media campaigns—a directive from Surgeon General Dr. Ralph Abraham that drew immediate backlash from the medical community.

Nine state medical organizations, including the Louisiana State Medical Society, issued a joint letter condemning the move: "Immunizations should not be politicized. Healthcare should not be politicized. Public health should not be politicized. Your relationship with your physician should not be politicized."

Dr. Vincent Shaw, president of the Louisiana Academy of Family Physicians, called the opposition unprecedented and warned that halting vaccine promotion could bring back diseases he's "only seen in textbooks, like measles and rubella." Meanwhile, Abraham has misrepresented his credentials, falsely identifying as a board-certified family medicine physician—raising serious concerns about the expertise guiding public health policy.

The consequences are already surfacing. Dr. Mikki Bouquet, a Baton Rouge pediatrician, reports growing parental skepticism about routine vaccinations. "Now parents are asking which vaccines are really necessary. That's absurd—it’s like asking which vitamin matters most. You need them all."

Even Republican Senator Bill Cassidy, despite voting to confirm RFK Jr. as HHS Secretary, has criticized the policy, warning that cutting vaccine outreach ignores the reality of parents' lives.

This shift underscores a troubling trend: political ideology overriding evidence-based public health, with the most vulnerable populations poised to suffer the consequences.

The Fight for Evidence-Based Solutions

This past week has marked a dangerous escalation of political interference in public health. The cancellation of vaccine advisory meetings, the halting of innovative vaccine development, and the downplaying of a deadly measles outbreak signal a fundamental shift away from science-based policy.

Healthcare professionals can no longer afford to stay on the sidelines. Beyond their clinical roles, they must become active policy advocates by:

Contacting state and federal representatives to oppose policies that undermine vaccination

Engaging with professional organizations to develop unified advocacy efforts

Providing expert testimony at legislative hearings on vaccine-related bills

Writing op-eds and speaking to media about vaccine safety and efficacy

Countering misinformation as trusted community voices

Supporting candidates who prioritize evidence-based public health policies

Medical organizations must also wield their influence more effectively. The recent joint statement from nine Louisiana medical groups demonstrates the power of unified action, while hospital systems—often major employers—hold political capital that should be used to safeguard public health infrastructure.

Community advocates play a critical role, too. Parents, faith leaders, and business owners can amplify vaccine messaging and reinforce public health norms. Even conservatives who support science-based medicine must speak out. As Senator Bill Cassidy’s rebuke of Louisiana’s vaccine policy shows, principled advocacy can transcend partisan divides when children's health is at stake.

The choice is clear: we either defend decades of vaccination progress or risk a return to the preventable suffering of the pre-vaccine era. Healthcare providers willing to advocate beyond clinic walls will determine which path we take.

DoxyPEP's Impact: New Evidence Shows Promise and Challenges in STI Prevention

After nearly two decades of rising sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) 2023 surveillance report reveals a welcome shift: overall STI rates dropped by 1.8% from 2022 to 2023. Gonorrhea cases declined by 7% for the second straight year, and primary and secondary syphilis fell by 10%—marking the first significant decrease in more than two decades. While these figures offer cautious optimism, questions remain about how best to sustain momentum, especially amid ongoing concerns about antimicrobial resistance and unequal access to prevention resources.

One potentially transformative intervention gaining traction is doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxyPEP). The CDC’s 2024 guidelines recommend doxyPEP for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), as well as transgender women, who have experienced a bacterial STI in the past year. Although clinical trials showed promising efficacy against chlamydia and syphilis, real-world data underscore nuanced challenges related to resistance, health disparities, and local healthcare capacity.

The Changing Landscape of STI Prevention

Several initiatives set the stage for the recent slowdown in STI rates. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provided funding to strengthen the disease intervention specialist workforce, bolstering capacity for targeted contact tracing and clinical follow-up. These efforts were amplified by new CDC recommendations that formalized doxyPEP for specific high-risk groups.

San Francisco became an early adopter of doxyPEP guidelines in October 2022, leveraging its established HIV prevention infrastructure and community partnerships. Early clinical trial data had shown marked drops in chlamydia and syphilis, prompting local officials to adopt prophylactic antibiotic use despite concerns over potential misuse and growing gonococcal resistance. Their experience would soon be mirrored and examined in other healthcare settings.

Real-World Evidence: San Francisco and Kaiser Permanente

Two new studies illuminate the impact of doxyPEP beyond controlled clinical environments. The first, conducted by the San Francisco Department of Public Health, examined STI rates before and after the city’s 2022 adoption of doxyPEP guidelines. Investigators reported a 49.6% drop in chlamydia and a 51.4% decline in early syphilis compared to what forecasts had predicted. Three sentinel STI clinics observed that 19.5% of eligible gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, as well as transgender women, initiated doxyPEP—a relatively high uptake for a new intervention.

A complementary Kaiser Permanente Northern California study included more than 11,000 participants already on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Those who added doxyPEP to their prevention repertoire saw chlamydia rates fall from 9.6% to 2.0% every quarter, while syphilis rates declined from 1.7% to 0.3%. These improvements closely mirrored prior clinical trial data, underscoring doxyPEP’s real-world effectiveness in high-risk populations.

However, the two studies diverged in their findings on gonorrhea. San Francisco observed a 25.6% increase in gonorrhea cases among the doxyPEP group, while Kaiser Permanente achieved a modest 12% reduction. Even in the latter setting, the intervention had varying efficacy based on infection site, with minimal impact on pharyngeal gonorrhea. Researchers attribute these discrepancies to existing tetracycline resistance patterns, which can range from 20% in U.S. gonorrhea strains to over 50% in certain regions globally.

Key Challenges to Implementation

1. Antimicrobial Resistance

Chief among concerns is the capacity of gonorrhea and other pathogens to develop resistance to tetracyclines. A modeling study in The Lancet warns that if doxyPEP achieves very high uptake—around 90%—it could lose effectiveness within just 1.6 years. More moderate adoption might prolong utility but still faces the ever-present risk that gonococcal strains could quickly evolve. The tension between scaling up prophylaxis to curb infections and preserving antibiotic utility for the long term remains a core dilemma for public health agencies.

2. Limited Healthcare Infrastructure

Successfully rolling out doxyPEP also requires robust clinical infrastructures. San Francisco’s early adoption relied on specialized STI clinics, disease intervention specialists, and strong community engagement. Such resources are scarce in many rural areas and underresourced urban centers, where STI burdens are often high. Without targeted funding and workforce development, these regions may fail to realize the potential benefits of prophylaxis. This gap underscores why a one-size-fits-all strategy for doxyPEP is unlikely to work uniformly nationwide.

3. Cost and Insurance Access

The Kaiser Permanente experience highlighted how commercial insurance coverage can determine doxyPEP uptake. Though Kaiser found no racial or ethnic disparities in its cohort, the ability to pay for routine tests and antibiotics remains a significant hurdle for many. Nearly half of all new STIs affect patients aged 15–24, a demographic often lacking stable insurance. Safety-net providers, such as community clinics and public health agencies, will need additional resources to prevent cost barriers from fueling inequities in STI prevention.

Addressing Health Equity

Disparities in STI burden persist despite national declines. CDC data show that Black communities—though comprising just 12.6% of the population—face roughly a third of all reported STIs, and American Indian and Alaska Native populations have the highest rates of syphilis. These patterns reflect structural inequities, from healthcare access to economic stability. DoxyPEP, if expanded, could either narrow or widen these gaps, depending on implementation strategies.

For example, the San Francisco Department of Public Health’s success relied on partnerships with community-based organizations that serve LGBTQ+ populations, bilingual outreach, and peer educators who could directly address stigma. Similar culturally tailored approaches will be crucial elsewhere. Nationally, any prophylaxis effort must acknowledge social determinants of health, from limited insurance coverage to historical medical mistrust, as central issues in achieving equitable outcomes.

Policy Recommendations

Meeting these challenges head-on requires collaboration among federal agencies, healthcare systems, and local organizations. Four policy domains stand out:

Robust Surveillance and Resistance Tracking

Establish or enhance regional testing to promptly detect shifts in gonococcal resistance.

Standardize reporting on doxyPEP uptake, stratifying data by race, ethnicity, and insurance status to monitor equity.

Integrated Healthcare Delivery

Incorporate doxyPEP into existing HIV PrEP programs, leveraging shared clinical workflows for ongoing STI screening.

Provide decision-support tools to guide providers in identifying those most likely to benefit from prophylaxis and in understanding local resistance rates.

Financing and Insurance Coverage

Secure coverage mandates or subsidies so that the costs of antibiotics and regular STI tests do not fall disproportionately on those most at risk.

Offer grants or incentives for safety-net clinics to scale up prevention services, including patient education and follow-up testing.

Antimicrobial Stewardship and Patient Education

Develop guidelines for targeted doxyPEP use to minimize unnecessary exposure—especially for gonorrhea, given its evolving resistance.

Emphasize correct usage and follow-up testing in patient education to ensure prophylaxis remains effective and that potential side effects are promptly reported.

Looking Ahead: Balancing Innovation and Stewardship

DoxyPEP’s success in specific cohorts highlights how targeted prophylaxis can substantially reduce chlamydia and syphilis infections. However, higher gonococcal resistance in some locales points to the need for continual surveillance and swift policy adjustments. Achieving a balance between curbing acute STI outbreaks and safeguarding long-term antibiotic effectiveness will require:

Adaptive Guidelines: Quickly revising prescribing recommendations if local data reveal resistance spikes.

Equitable Implementation: Ensuring consistent uptake in historically underserved communities, rather than concentrating benefits among those with robust insurance.

Global Collaboration: Sharing best practices and emerging data to keep pace with evolving gonococcal strains and develop new therapeutic agents or vaccines.

Conclusion

The modest national declines in STI rates are a reminder that with strategic investments and coordinated interventions, progress is possible. DoxyPEP stands out as a promising addition to the prevention toolbox—particularly for chlamydia and syphilis—when backed by sufficient testing, monitoring, and community outreach. Yet the specter of antimicrobial resistance, along with ongoing disparities in healthcare access, underscores that a single biomedical solution must be carefully managed.

Findings from San Francisco and Kaiser Permanente prove doxyPEP can effectively reduce STI incidence in real-world settings. Whether it remains a durable tool will depend on collective commitment: policymakers must fund surveillance and outreach, clinicians must practice stewardship, and communities must engage to ensure equitable access. If implemented wisely, doxyPEP could shape a future where the burden of STIs—and the inequalities that fuel them—diminish, showcasing how targeted prevention strategies can enhance public health without jeopardizing our arsenal of antibiotics.

Partisan Battles Put Public Health Programs in Jeopardy

Federal support for public health programs stood at a critical inflection point in 2024, with mounting evidence that political polarization threatens to undermine decades of progress in disease prevention and healthcare access. The O'Neill Institute's analysis of the HIV response highlights a broader pattern affecting America's entire public health infrastructure: an erosion of bipartisan cooperation is creating tangible negative impacts on healthcare delivery and outcomes.

Recent developments illustrate this crisis. The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), historically celebrated as one of the most successful public health initiatives in U.S. history, received only a one-year reauthorization in March 2024 instead of its traditional five-year renewal. This shortened timeframe introduces uncertainty for partner countries and threatens program stability. Similarly, Tennessee's rejection of $8.3 million in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV prevention funding exemplifies how state-level political decisions can directly impact public health services and infrastructure.

The implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), while advancing certain healthcare affordability goals, has created unintended consequences for safety-net providers. Changes to drug pricing and reimbursement structures are affecting 340B program revenues that support critical healthcare services for vulnerable populations.

These challenges emerge against a backdrop of chronic underfunding, with the Prevention and Public Health Fund losing $12.95 billion between FY 2013-2029. This combination of political polarization and resource constraints threatens to create long-lasting negative impacts on healthcare access and population health outcomes, demanding a renewed commitment to depoliticizing essential public health infrastructure and services.

An Erosion of Bipartisan Support

The deterioration of bipartisan cooperation in public health policy represents a significant shift from historical norms that prioritized health outcomes over political ideology. PEPFAR exemplifies this change. Created under President George W. Bush's administration in 2003, PEPFAR has saved over 25 million lives and currently provides HIV prevention and treatment services to millions across 55 countries. Despite this documented success, the program's 2024 reauthorization became entangled in partisan debates over abortion rights.

"I'm disappointed," Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas) stated. "Honestly, I was looking forward to marking up a five-year reauthorization, and now I'm in this abortion debate." McCaul added that "a lot of the Freedom Caucus guys would not want to give aid to Africa." The inclusion of abortion rights in the reauthorization debate reflects ongoing polarization within Congress, which has hindered the passage of traditionally bipartisan public health initiatives. This opposition led to an unprecedented short-term reauthorization through March 2025, creating instability for partner countries and threatening program sustainability.

At the state level, Tennessee's decision to reject $8.3 million in CDC HIV prevention funding reflects similar political calculations overshadowing public health considerations. The state's choice to forgo federal support impacts disease surveillance, testing services, and prevention programs that serve people living with HIV and those at risk of acquiring HIV. This rejection of federal funding occurred despite Tennessee ranking 7th among U.S. states for new HIV diagnoses in 2022.

Such decisions mark a stark departure from historical bipartisan support for public health initiatives. Previous health emergencies, from polio to the early HIV epidemic, generated collaborative responses across party lines. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, established in 1990, exemplified this approach, receiving consistent bipartisan support for reauthorization until 2009, its last reauthorization.

The shift away from bipartisan cooperation extends beyond specific programs to affect broader global health initiatives. PEPFAR's instability impacts America's global health leadership position and threatens the progress made in HIV prevention and treatment worldwide. The program's uncertain future affects procurement planning, workforce retention, and long-term strategy development in partner countries, potentially reversing decades of progress in global health security.

Funding Crisis and Infrastructure Impacts

The public health funding landscape reveals a pattern of chronic underinvestment that threatens core infrastructure capabilities. The Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF), established under Section 4002 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) to provide sustained investment in prevention and public health programs, has lost $12.95 billion between FY 2013-2029 through repeated cuts and diversions. These reductions represent approximately one-third of the fund's originally allocated $33 billion, significantly limiting its ability to support essential public health services.

The CDC faces mounting infrastructure challenges due to stagnant funding. While COVID-19 response funds provided temporary relief, these emergency appropriations have been largely obligated or rescinded. The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 rescinded approximately $13.2 billion in emergency response funding from public health agencies, including the CDC, creating a significant funding cliff. Programs facing severe reductions include the Advanced Molecular Detection program, which will revert to its annual base appropriation of $40 million from a one-time supplemental of $1.7 billion, severely limiting disease surveillance capabilities.

State-level impacts manifest in critical staffing shortages and outdated systems. Public health experts estimate that state and local health departments need to increase their workforce by nearly 80%, requiring an additional 26,000 full-time positions at the state level and 54,000 at the local level. The National Wastewater Surveillance System, crucial for early detection of disease outbreaks, faces reduction from $500 million in supplemental funding to a proposed $20 million in FY 2025, threatening its operational viability.

These funding constraints create cascading effects across the public health system. The Public Health Infrastructure Grant program, which has awarded $4.35 billion to strengthen foundational capabilities across 107 state, territorial, and local health departments, expires in FY 2027 without a clear sustainability plan. Similarly, the Bridge Access Program, ensuring COVID-19 vaccine access for 25-30 million adults without health insurance, ended in August 2024, leaving millions without access to updated vaccines. These funding cuts have significantly curtailed prevention services, limiting the CDC's ability to maintain disease surveillance systems and provide timely interventions.

Healthcare Access and Safety Net Impacts

The implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has created unintended consequences for safety-net providers, particularly through its impact on the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Research examining 340B-eligible hospitals reveals concerning trends in charity care provision, with only 9 out of 38 hospitals (23.7%) reporting increases in charity care as a percentage of annual revenues after gaining 340B eligibility. This decline in charity care occurs despite significant revenue increases from 340B participation, raising questions about program effectiveness in expanding healthcare access for vulnerable populations.

Data indicates that hospital participation in the 340B program correlates with substantial revenue growth but diminishing charity care services. The average decrease in charity care provision as a percentage of annual revenues was 14.79% across examined hospitals. This trend is particularly concerning in states with high poverty rates. For example, three West Virginia hospitals—Cabell-Huntington Hospital, Pleasant Valley Hospitals, and Charleston Area Medical Center—reported some of the largest decreases in charity care despite serving a state where 28.1% of people earn less than 150% of the Federal Poverty Level.

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) face unique challenges under these changing dynamics. Unlike hospitals, FQHCs must reinvest every 340B dollar earned into patient care or operations to maximize access. However, the IRA's implementation of Medicare drug price negotiations and insulin cost caps affects the rebate calculations that support these reinvestments, potentially reducing available resources for patient care.

Medication access challenges extend beyond 340B implications. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) have responded to IRA provisions by adjusting formularies, sometimes excluding medications that previously generated significant rebates. This particularly impacts insulin coverage, where certain products have been dropped from formularies despite the IRA's intent to improve insulin affordability. These decisions create new barriers to medication access for people who rely on safety-net providers for healthcare services.

Public Health Consequences

The convergence of political polarization and funding constraints creates measurable negative impacts on disease prevention efforts, weakening the capacity of public health systems to effectively address emerging and ongoing health threats. Data from the CDC shows that despite a 12% decrease in new HIV diagnoses over the past five years, driven largely by a 30% reduction among young people, progress in reducing new infections has stalled. The lack of sufficient funding, compounded by political challenges, has limited the capacity to expand prevention services, enhance outreach, and maintain necessary treatment programs. The 31,800 new HIV diagnoses reported in 2022 highlight how flat funding and political barriers have hindered further advances. These barriers prevent scaling up successful prevention strategies, limit access to innovative treatments, and constrain efforts to address disparities in vulnerable communities. Notably, significant disparities persist, particularly among gay men across all racial and ethnic groups, transgender women, Black people, and Latino people. These populations continue to face systemic barriers to healthcare access, stigma, and a lack of targeted resources, all of which contribute to ongoing inequities in health outcomes.

Vaccine hesitancy, intensified by political division, threatens population health outcomes. The CDC reports that routine vaccination rates for kindergarten-age children have not returned to pre-pandemic levels, while exemption claims have increased. Nearly three-quarters of states failed to meet the federal target vaccination rate of 95% for measles, mumps, and rubella during the 2022-23 school year, increasing outbreak risks.

Health disparities are exacerbated when political decisions override public health considerations. Tennessee's rejection of CDC funding exemplifies how political choices can disproportionately impact communities already experiencing health inequities by reducing access to essential prevention and treatment services. Such decisions particularly affect regions where HIV rates among transgender women increased by 25%, and Latino gay men now account for 39% of all HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men.

Community health center sustainability faces mounting challenges as funding mechanisms become increasingly unstable. The expiration of COVID-19 emergency funding, combined with uncertain 340B revenues and growing workforce shortages, threatens these essential safety-net providers. Public health experts estimate an 80% workforce gap in state and local health departments, hampering their ability to deliver essential services and respond to emerging health threats.

Uncertain Future Under New Administration

With Donald Trump’s return to the White House, the future of the nation's public health programs remains uncertain. The president-elect’s stance on health policy has historically emphasized deregulation, work requirements, and reductions in safety net programs, and early indications suggest a continuation of these priorities.

The new administration is poised to bring changes that could scale back Medicaid, reduce the Affordable Care Act’s consumer protections, and restrict reproductive health access—all of which have the potential to exacerbate existing health inequities and widen the gap in healthcare access for marginalized populations. Furthermore, the inclusion of vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. among Trump’s advisors could undermine public confidence in vaccination campaigns and other science-backed public health interventions.

Although Trump has not explicitly targeted programs like PEPFAR, the Ryan White Program, or other core public health initiatives, the broader agenda of cutting federal funding and shifting health policy decisions to the state level raises significant concerns. These shifts could ultimately weaken the country’s safety net programs, leading to an increase in uninsured rates and preventable health disparities.

The reemergence of a more partisan approach to healthcare policy, especially one with a focus on cost-cutting and minimal regulatory oversight, risks destabilizing public health progress made over the last several decades. Public health stakeholders—ranging from healthcare providers to patient advocates—will need to prepare for a period of heightened uncertainty and potentially significant changes to the public health landscape.

The coming months will likely determine how public health priorities and programs evolve in this new political era. Advocacy groups, healthcare professionals, and policymakers must remain vigilant and ready to respond as the Trump administration shapes its healthcare policy agenda, one that could either sustain or significantly alter the course of public health in the United States. Such shifts threaten to undermine the nation’s public health stability, with repercussions for healthcare costs, access, and the ability to prevent and control emerging health threats.

New CDC Report; More than a Decade After a Cure, HepC Persists

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a Vital Signs report detailing how “too few people” are being “treated for Hepatitis C” (subtitled: “Reducing Barriers Can Increase Treatment and Save Lives”). Today, the CDC’s landing page reflects a finding from April 2020 that reads “dramatic increases in Hepatitis C” (subtitled: “CDC now recommends hepatitis C testing for all adults”). And in late June, the CDC published a new Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) on a worryingly low rate of HCV clearance in the United States.

Our previous blog reviewed last year’s report under the lens of health disparities highlighted by researchers’ review of 48,000 patient charts that met the inclusion criteria for the analysis. Then, much like in this new report, identified that lack of curative treatment access was not uniform and was largely informed by the type of insurance patients qualified for. Those payer types (Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial plans) also represent patients from different backgrounds – meaning different socio-economic statuses, different genders and racial backgrounds – with different outcomes. Overall, Medicaid recipients were only ever prescribed curative treatment about 23% of the time, whereas Commercial payer patients were able to see that rate increase to 35%. The CDC also recognized these payers, and the politicians who set the public policy of Medicaid, represent incredibly tangible barriers via administrative processes, like prior authorization, and policy barriers, like requiring sobriety, a high level of liver damage, or other restrictions to gaining access to curative treatments.

For this year’s report, researchers partnered with Quest Diagnostics to review the viral clearance (or cure) of approximately 1 million patients with an initial infection (Quest provided data for 1.7 million patients with evidence of a history of HCV during the direct acting agents era, or from January 1, 2013 – December 31, 2022). Based on an estimated 2.4 million people in the United States with HCV, this sample represents about 43% of those believed to have experienced an HCV infection in this time frame. This is noted as a limitation in the data, in part, because it only represents data from one commercial laboratory. Though, reasonable observers can make certain conclusions from this data.

Now, we should also note, only about 88% of the 1.7 million patients identified as having evidence of HCV infection ever had received testing and, of those, 69% were identified as having an initial infection. This means the majority of patients identified were newly diagnosed and not facing a chronic HCV infection. Of those, about 7% of patients showed evidence of viral persistence.

Authors note “These findings reveal substantial missed opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent Hepatitis C in the United States.”

Coverage was highest among those enrolled in commercial insurance (50%) and lowest in Medicare and Medicaid (8% and 9%, respectively). Particularly startling in the differences between payer types was the prevalence of viral testing; those with an unspecified payor type were screened at about 79% and those with commercial insurance or Medicare had a testing prevalence of about 91%.

Patients with “other”, “unspecified”, or Medicaid as their insurance or payer had showed a lower viral clearance rate (23%, 33% and 31% respectively) than their counterparts enrolled in Medicare or commercial plans (40% and 45%, respectively). Overall, the cure rate was about 34%.

The age range with the highest rate of HCV diagnoses was 40-59 years, representing about 43% of the patient records reviewed. 60% were identified in their charts as male. However, the highest rate of viral clearance was among those aged over 60 and the lowest was for those aged between 20-29 years.

Other limitations to the data include a lack of uniformity in the follow-up period between testing, which might lead to some difference in rates. Similarly, patients might use or be referred to a different lab for follow-ups. Though, the data also does not follow patients and would not capture any representation of subsequent reinfection and cannot make any assumptions as to clearance or viral persistence among those who did not have RNA testing (and referral for treatment) – meaning the data likely underestimates the patients in each of these categories.

Advocates can look toward these data and findings to inform necessary policy changes, particularly by payer type and in seeking appropriate provider activation on screening and treatment. The sheer reality is HCV is both preventable and curable and policymakers and payers need to work more efficiently in order to prevent the approximate 14,000 HCV related deaths this country faces annually.

Opioid Settlements in America

In 2021, a group of state State Attorneys General announced a $26-billion national opioid settlement with three of the largest drug distributors—McKesson Corp., Cardinal Health, Inc., and AmerisourceBergen Corp.—and drugmaker Johnson & Johnson that would see $21b and $5b from those groups, respectively. This settlement deal was approved by all but four states—Alabama, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Washington—and distribution of those funds began in 2022.

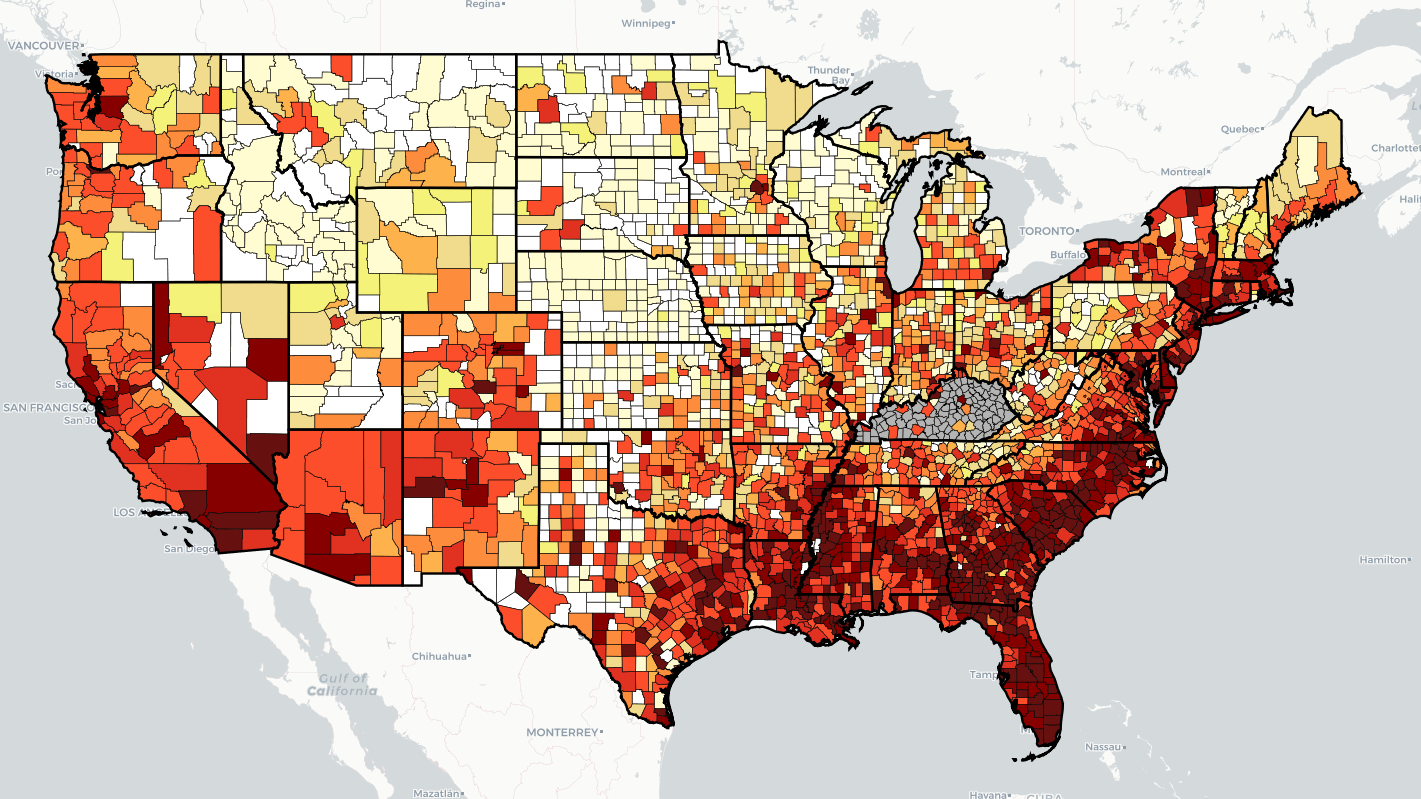

As with every such settlement, funds are distributed to states and municipalities, but how those funds are used is largely up to the recipients. One of the primary critiques of the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement was that states and municipalities could use the settlement funds for any purpose. Many states, including West Virginia, used (and abused) those funds to plug holes in their budgets, fund infrastructure improvements, and, in the case of West Virginia, fund teacher pension funds. This lack of direction and oversight meant that relatively few funds actually went to provide healthcare, cessation, or prevention services. Despite this, adult smoking rates have largely plummeted since 1998 but remain relatively high in Appalachian and Midwestern states (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Current Cigarette Use Among Adults (Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System) 2019

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, October 22). Map of Current Cigarette Use Among Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/cigaretteuseadult.html

Negotiators appear to have learned from that mistake, and the National Opioid Settlement is different. However, while the settlement agreement requires that 85% of the funds going directly to states and municipalities must be used for “…abatement of the opioid epidemic,” the settlement doesn’t go so far as to enumerate what qualifies as “abatement.”

According to Kaiser Family Foundation reporting, funds from the settlement are split between states and are then divided in varying percentages across state agencies, local governments, and councils that oversee opioid abatement trusts. But, there has been little transparency around the settlements, including how much each state is received, how those funds are then divided, and how those funds will be used. To date, just 15 states (Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Idaho, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah) have explicitly promised to report 100% of their Distributor and Johnson & Johnson settlement expenditures. These promises are not, however, legally binding, and recent moves by certain state administrative and legislative bodies to make private information that is statutorily mandated to be public under state Sunshine Laws bode poorly for those hoping to hold states accountable for their use of the funds.

There have been some successful efforts to track the distribution of national settlement funding out of the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP). Their map, however, is limited in that it only covers funds from that National Opioid Settlement, meaning that states that chose to continue pursuing additional damages (i.e., West Virginia, Alabama, Oklahoma, and Washington) are not tracked on the map. In addition to the interact map, NASHP provides a pretty comprehensive breakdown of how each state is using opioid settlement funds, including those states that did not participate in the national settlement.

Because we’re still in the early days of the settlement disbursements, there’s not really a great way to measure whether or not the funds will be successfully utilized, nor whether or not the abatement programs will actually have an impact. What we have seen outside of the settlement is that there is little consensus between states on how best to approach the continuing opioid epidemic. While some states increased access to harm reduction services, others have reduced access to, heavily regulated, or eliminated those services altogether.

In states where the opioid epidemic has become part of the fabric of life, such as Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, anecdotal reports and some limited research have found that, while additional and public health professionals are actively attempting to implement policies, plans, and interventions to openly and positively confront the opioid crisis, state residents are simply exhausted after dealing with over twenty years of devastation, loss, and both perceived and real destruction to their ways of life.

On the anecdotal front, I recently returned to Eleanor, WV, where I briefly lived and attended school and where my father taught music. What I found made my heart ache: the town’s lone shopping center essentially abandoned and left in disrepair; a middle school whose track and football field (which are still actively used by students) so destroyed that the track was little more than broken concrete loosely interspersed between fields of overgrown grass and bleachers literally tilting from rust and overuse; a set of buildings that once served as some of the town’s few apartment buildings literally burned out and boarded up with graffiti-covered plyboard; school bus stops that looked like they’d been hit by a tornado, and nobody repaired them.

We’re not talking about a major metropolitan area—we’re talking about a town of just over 1,500 residents that carries the moniker, “The Cleanest Town in West Virginia.” And the devastation didn’t stop there. I spent the next hour or so driving along the routes I used to travel as a kid and teenager, and every place that once held a great memory for me was absolutely destroyed or so badly damaged as to be wholly unrecognizable.

When I go through Facebook to check on friends from my time in Eleanor, a significant percentage of them are either recovering, in active use, or have lost their lives to the opioid epidemic. Even after working in the public health and advocacy space for more than fifteen years, the realities sometimes feel remote, and this drive allowed me to see what the opioid epidemic has done to West Virginia: it has deprived us of hope that things can or will get better. What’s more, our state legislature seems determined to make things worse.

These are the states and towns where opioid settlement funds are desperately needed, but it’s unclear whether or not they will receive or utilize them well. I know that I will be actively following how these funds are used in Appalachia, particularly in my capacity as Founder and Executive Director of the Appalachian Learning Initiative (APPLI, pronounced like “apply”).

Australia is on Track to End HIV…by Focusing on Treatment

Last week, researchers funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia published an assessment of Australia’s success in combatting HIV and how the country might meet its goals to end their domestic HIV epidemic. The study is remarkable in many ways and readers should be cautioned to appreciate the various differences in dynamics between the epidemic in their country of residence and Australia. For example, Australia has been willing to get creative with its policy and program environment and infrastructure to address barriers to care – something many other countries, including the United States, might face steeper challenges in doing.

The study, which focused itself in New South Wales and Victoria – the country’s most populous states. While these areas hold large urban populations, Melbourne and Sidney for example, they also have large rural geographies as they get closer to the interior of the country. This isn’t dissimilar to much of the United States, where the coasts and land boarders, to a lesser degree, are well populated and as you get closer to the interior of the country, that population becomes more rural. Rural and urban geographies present very unique dynamics in and of themselves. And those differences should be well-appreciated when considering the findings of the study.

Specifically, the study sought to assess “whether treatment-as-prevention could achieve population-level reductions in HIV incidence among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM)”.

What’s most interesting about the study – though not necessarily surprising given historical evidence – is it found a positive correlation between increasing viral load suppression and reduction of new HIV diagnoses. But it’s not a 1-to-1 ration. The study found a 1% increase in viral load suppression was associated with a WHOPPING 6% decrease in new diagnoses. That’s not all folks – that decrease was AFTER an adjustment to account for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), meaning the 1-to-6 correlation between increased viral load suppression and reduction of new diagnoses was INDEPENDENT of PrEP uptake and use.

Now, that’s not bash PrEP. Rather, the authors argue that to achieve maximum benefit, PrEP should continue to be partnered with our understanding of treatment-as-prevention, or, as messaging goes, Undetectable Equals Untransmittable (U=U). Indeed, the data from the study spans 10 years, which means the authors were able to positively demonstrate how PrEP increases the successes related to treatment-as-prevention.

Authors conclude their work with a direct interpretation: “Our results suggest that further investment in HIV treatment, especially alongside PrEP, can improve public health by reducing HIV incidence among BGM.”

This work is especially important as the United States begins considering a nationalized PrEP program and making exceptional investments in doing so. This study very specifically reminds us that we will NOT reach our goal of ending the HIV Epidemic with PrEP alone…but we might with treatment-as-prevention. And if we were forced to do so with treatment alone, we might still get there if we could overcome barriers to care like stigma, unnecessary barriers to care like utilization management practices, employers leveraging their power in the private market, meeting people where they physically are, closing gaps between “available” and “accessible”, overcoming discriminatory actions aimed at harming those already most affected by HIV, and more.

There’s another advantage in not moving onto PrEP with a near exclusive fervor, HIV treatment is directly life-saving. It is the humanitarian and right thing to do to ensure people already living with HIV are receiving the care and treatment and resources and support we need to thrive.

Directly, this data shows us that we will not defeat HIV by only focusing on people not already living with HIV. Rather we must ensure the lion’s share of our work focuses on people already living with HIV.

There’s much work to do and much promise on the horizon.

I’ll leave advocates with this and a request to search internally.

In December, HBO will be releasing a documentary on the Honorable Nancy Pelosi. The trailer for it is out already. In one clip, one quote, Representative Pelosi, one of our dearest champions, summarizes where our work should guide us, “I came here to do a job, not keep one.”

A Pox in the Hen House: A Timeline of the MPV Outbreak and Topline Numbers

The first Monkeypox (MPV) diagnosis in the United States was reported on May 17th, 2022, though testing data indicate that the first test that returned a positive result was administered on May 10th. By July 3rd, 2022, there were over 1,500 reported cases in the United States.

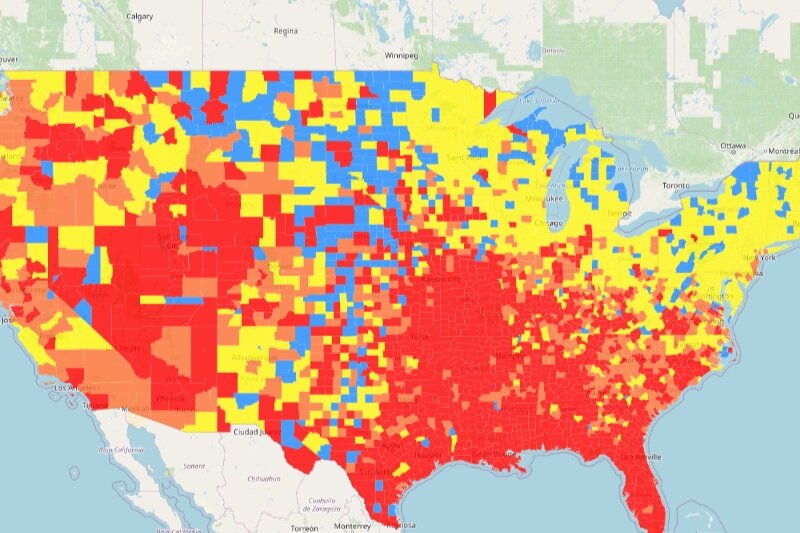

By early July 2022, white Americans accounted for 47.6% of MPV diagnoses. But by July 24th, 2022, with 7,266 cumulative MPV diagnoses, Black Americans for the first time accounted for most positive diagnoses—32.6%—in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Week 30. For all but 8 out of the following 28 weeks (ending in MMRW Week 5, 2023), Black Americans accounted for the highest percentage of positive test results. White Americans accounted for the majority of weekly positive diagnoses in only 7 weeks in that same period of time. On August 9th, 2022, the U.S. government declared MPV a Public Health Emergency (PHE). As of February 15th, 2023, there have been a total of 30,193 identified MPV diagnoses and 38 confirmed deaths as a result of MPV.

On May 22nd, 2022, the first JYNNEOS vaccines were administered as prophylaxis against MPV in the United States. Initial supplies of the MPV vaccine were low, however, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to increase the available supply, issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) on August 9th, 2022, allowing healthcare providers to administer the vaccine in a two-dose series using intradermal administration based on findings from a 2015 study that evaluated the efficacy of intradermal compared to subcutaneous vaccine administration. The total number of vaccines administered in a single week peaked in the week of August 7th – August 14th, 2022, with 108,895 total vaccines administered. By September 10th, 2022, the number of weekly second doses administered outstripped the number of first doses for the first time. This trend continued until the week ending on January 28th, 2023. The number of weekly vaccine administrations dropped precipitously in the week ending on October 1st, 2022. As of February 28th, 2023, a total of 1,196,047 doses of the MPV vaccine have been administered.

Access to and administration of the MPV JYNNEOS vaccine in the United States appear to have been highly correlated to race. In both First- and Second-Dose administration phases, white Americans were the most likely to be vaccinated, with 46.4% of first doses and 50.3% of second doses being administered to white Americans. White Americans received 47.9% of all vaccines administered. Despite the fact that Black Americans represented the highest percentage of diagnoses in the United States—33.7%—just 11.3% of first doses and 10.7% of second doses were administered to Black Americans, receiving just 11.1% of all vaccines administered. Among Hispanic Americans—who accounted for 29.6% of all MPV diagnoses in the United States.—just 20.7% of first doses, 19.6% of second doses, and 20.3% of total doses were administered to this population.

The first doses of TPOXX (tecovirimat) for the treatment of severe MPV disease were prescribed on May 28th, 2022. TPOXX administration is primarily reserved for patients with severe symptoms of the disease, who are immunocompromised, or who have other concurrent conditions that may present complications. As of January 25th, 2023, 6,832 patients were prescribed or treated with TPOXX.

On November 28th, 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO), to address racist and stigmatizing language associated with MPV recommended a global name change for the virus to “MPOX.” (Disclaimer: CANN continues to use “MPV” for its current project merely for the purpose of consistency in report language, but will begin using “MPOX” upon conclusion of the project)

On December 3rd, 2022, the U.S. government announced that it would not be renewing the PHE for MPV. The PHE officially expired on January 31st, 2023.

The Lessons We Applied, the Ones We Learned, and the Ones We Failed to Heed

One of the most successfully applied lessons was the implementation and utilization of existing testing, vaccination, and surveillance systems that were created in response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Of the 57 reporting U.S. jurisdictions, 31 utilized their existing disease response, reporting, and tracking infrastructures to deploy in-depth disease MPV surveillance for the majority of the outbreak. The surveillance staff and protocols developed during the COVID-19 pandemic quickly pivoted to include MPV in their work, expanding their disease reporting and dashboards to include MPV case counts and demographics to better track the outbreak. Existing vaccine infrastructures including, but not limited to, staffing, scheduling systems, and drive-through delivery spots, were adapted, expanded, or repurposed to incorporate MPV vaccine supplies and dose administration.

Several jurisdictions truly set standards in their reporting, including the states of California, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New York City (which is reported separately from New York state). They provided excellent MPV diagnosis demographic breakdowns that included age groups, racial/ethnic minority categories, and gender reporting that included trans, non-binary, and other gender expression categories. These data helped to direct responses and better measure equitable outreach, education, and access to treatment and vaccines to the most affected communities.

To hear state and federal public health officials tell it, the U.S. response to the MPV outbreak has been a masterclass in how to effectively respond to and control an epidemic of a highly infectious disease. We’ve heard about how successful and swift the response to the outbreak was and, for a certain segment of the population, that may be true.

For many white, cisgender men who have sex with men (MSM), the outbreak has been little more than a month-long inconvenience; a blip that barely pinged their radars. The other side of that story, however, lies in the marginalized demographic groups.

For all of the successfully deployed public health systems, the truth is that MPV has been almost exclusively a disease that impacts the “others” in our society. From the beginning of the response, LGBTQ+ patients reported facing stigmatizing, discriminatory, and/or outright racist attitudes and behaviors on the part of medical professionals and administrative staff, particularly those seeking services outside of urban settings.

The unfortunate truth of healthcare provision is that every disease that is primarily acquired via sexual transmission comes with its own set of social, moral, and medical stigmata. In areas where self-reported levels of religiosity are high, patients seeking care often encounter negative behaviors and reactions from healthcare workers and administrative staff both inside and outside of the STD/STI/HIV spaces. While the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is supposed to protect patients, the reality on the ground is that healthcare workers can be woefully loose-lipped when it comes to sinking the social ships of the patients who live in small or close-knit communities. Moral judgments are made; stories get told; patients are admonished and made to feel ashamed—the impacts of these behaviors, both short- and long-term, can lead to patients refusing to seek testing or treatment until they feel they absolutely must, to avoid being honest with physicians about their symptoms, or to refuse to seek vaccinations or treatment services to help prevent infection or the further spread of the disease.

When it came to the delivery of MPV vaccines, the splitting of the JYNNEOS vaccine into two doses both created confusion about the efficacy of the vaccine and increased barriers to people wishing to complete the two-dose series. With any vaccine series, the fewer times patients need to schedule or show up for an appointment to receive their shots, the more likely they are to get fully vaccinated. Additionally, the decision to use intradermal vaccine administration as the delivery method—one of the more difficult delivery methods to correctly perform—resulted in reports of unsuccessful attempts at vaccinating individuals, particularly in patients with darker skin. Additional concerns, which were only marginally addressed by later guidance—and inconsistently applied across jurisdictions and providers—included discomfort and scarring, particularly among those prone to keloids. This meant that several patients—mostly Black and Brown—had to have their dose readministered at a later date creating yet another unnecessary barrier to becoming fully vaccinated.

Another factor that negatively impacted the MPV vaccine uptake was the exponential increase in self-reported hesitancy, skepticism, refusal, and beliefs in scientifically and factually inaccurate information about vaccines, in general. One of the worst consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic response was the massive influx of false information about how vaccines are developed and manufactured, what their contents are, their risks and side effects. Those challenges were compounded by misinformation, such as massive government/billionaire/Jewish/Chinese conspiracies to commit every farcical atrocity under the sun – including surreptitiously implanting microchips, giving people mutant magnetic properties, sterilization…you name it, some shadowy organization was allegedly doing it.

Despite these falsehoods being easily disproven within seconds, for many people the burden of proof has never been on the people making the false claims to prove their theories, but on the “experts” to disprove what the neighbor’s cousin’s sister’s oldest great-grand-nephew said about how the vaccine caused him to go blind.

Beyond those haphazardly manufactured and too easily consumed lies about vaccines, Black and Brown communities have historically legitimate reasons to distrust the government and medical authorities. Decades of actual and well-documented surreptitious sterilization, non-consensual experimentation, and abuse at the hands of systemically racist medical establishments have resulted in a generational and almost endemic distrust of public health measures, treatments, and authorities in minority communities. Efforts to combat generational hesitancy, avoidance, and distrust are slow-going, taking decades of work to undo or repair the harm that has been done to those communities. Add on top of that steady and relatively unchallenged social, digital, and visual media streams churning out anti-vax conspiracy theories, and that process becomes all the more difficult.

In Black and Hispanic men, as well as in communities of Persons Living With HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), MPV was largely allowed to run rampant, in no small part because of ineffective, lacking, or wholly absent educational, outreach, and vaccination strategies designed to reach those communities. While the work done by Drs. Demetre Daskalakis and David Holland in the Atlanta region and in a handful of other major cities was both highly effective and admirable, reality is that their campaign of taking education, testing, and vaccination drives into large-scale venues, gay cruises, fetish events, and sex clubs simply wasn’t scaled and replicated at the levels needed to truly reach those most in need of services.

One of the lessons that we need to learn from the MPV outbreak is that we need to do a much better job of delivering healthcare services outside of traditional settings and offering healthcare services outside of traditional office hours.

We already know that rural, minority, and LGBTQ+ populations face critical healthcare staffing and service provision shortfalls. The closure of rural clinics and hospitals, as well as healthcare providers who served primarily minority and/or lower-income patient populations, has exacerbated the negative outcomes and barriers that exist in areas with underfunded, little, or non-existent healthcare infrastructures. While the growth of COVID-19-related pop-up services and locations provided hope for improvement, the truth is that those investments were never designed to be long-term, nor were those investments or their implementation welcomed in more conservative parts of the country.

If we want to effectively serve underserved populations, we must think and act outside of the standalone brick-and-mortar healthcare paradigm. The MPV outbreak has shown us that we need to significantly increase local, state, and federal investments in mobile, pop-up, and telehealth healthcare delivery methods and models to meet people where they are. We also need to invest in more community-based providers, service models, and interventions. We need more public-private collaboration design – like the New York City Health Department partnering with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence for generating a community experiences feedback system.

Many of the most innovative and successful STD/STI/MPV interventions don’t require patients to come into a standard physical location to access testing, vaccination, and treatment services. They are set up in sex clubs and bars; they show up at concerts, parties, and other big events; they offer services in churches in communities where faith plays an important role in the lives of their patients; they build trust in, develop relationships with, and take mobile units into encampments of people experiencing homelessness. Essentially, they go out and meet patients where they are and when they’re available. A pox in the hen house has taught us one very valuable lesson: we need to fix these barriers sooner rather than later.

When MPV Became An STI

There comes a time, in the progression of any outbreak, where classifications change as we grow to understand more about the disease; a time when people—those who are living with the disease, those who have recovered, those who have never come in contact, and those who encounter the disease in a professional capacity—decide that we’re no longer in the midst of an “outbreak,” but that it has either ended or become endemic. This is where we appear to be with the Monkeypox (MPV) outbreak in the United States.

Since the beginning of the MPV outbreak in the United States, the overwhelming majority of cases have been transmitted via sexual contact (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022), primarily among men (CDC, 2023), particularly among Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) (Spicknall, et al., 2022), and disproportionately among Black Americans (CDC, 2023). The Community Access National Network (CANN) has been actively tracking reporting of MPV since September of 2022, and in that time, we have witnessed a troubling pattern emerging: the celebration of a “successful” control and suppression of a disease outbreak when the disease actually risks becoming endemic.

When we say that a disease has become endemic, it means that the disease is a constant presence in a certain population within a specific geographic region. In this case, we mean that MPV has relatively rapidly transitioned from a highly concerning outbreak to one that is being treated as a sexually transmitted infection (STI) similar to syphilis—one that is likely going to just “be around” no matter what we do. In the MSM communities that have been overwhelmingly impacted by MPV, members of those communities have already started treating it as such:

“We know it is how we are getting it, we just don’t know what to do about it because, based on lesion location alone, for example, a condom would not have prevented some of these exposures.”

This comment from an HIV activist and advocate living in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen was related to me during a conversation about anecdotal reporting of disease outbreaks in the area.

“I know of at least a dozen men in the last couple of weeks who are experiencing minor infections despite being vaccinated or previously infected, and this week, I have seen several sex workers in the streets around here who are clearly experiencing full-blown infections, implying no vaccination.”

These statements raise several concerns, not the least of which is the availability of vaccine supplies and the distribution of said vaccine among priority populations. Additional concerns include what, if anything, can be done to curb the spread of MPV among MSM populations when vaccine supplies are unable to keep up with the demand if the virus is, in fact, becoming endemic. Will we simply decide, as a nation, that it’s just something we have to live with and move on with our lives?

One of the unfortunate truths about the availability and distribution of the MPV vaccine is that the populations who were the most disproportionately impacted by the virus were some of the least likely to receive the vaccine. As of January 19th, 2023, 48.3% of vaccines administered have been administered to White residents, despite the fact that just 22.4% of MPV cases have occurred in White residents. Comparatively, 34.7% of MPV cases have been identified in Hispanic residents, with just 23.4% of vaccines going to that population, and 27.4% of MPV cases have been identified in Black residents, with just 12.8% of vaccines going to that population.

Essentially, vaccination outreach efforts have simply not been sufficient to reach the populations most heavily impacted by the disease. While many factors may contribute to this outcome, the primary factor is that Black and Hispanic Americans simply do not have access to or receive the quantity and quality of care that White Americans enjoy—a fact that has been widely discussed but poorly addressed since the early 2000s (Collins, et al., 2002). From the quality of the facilities and services to the availability of service providers, White Americans are more likely to have access to not just more healthcare services but better services that meet their needs, whereas Black and Brown Americans are made to deal with longer wait times, under-resourced and understaffed facilities, and often lower quality care.

While there certainly have been efforts to reach into Black and Brown communities to deliver the same quantity and quality of healthcare services, healthcare workers come up against cultural barriers, including having to confront the generations of discrimination, mistreatment, and neglect that Black and Brown Americans have faced from healthcare professionals that make those populations less likely to seek healthcare services and trust providers.

These are the same barriers that people working in the HIV and STD/STI fields face when trying to provide services, and we still struggle to overcome those barriers today, although progress is being made, particularly when healthcare services are provided by members of those communities whom they know and trust. The same logic can and should apply to the delivery of vaccines, but the sad reality is that vaccine hesitancy and refusal continue to be high in Black and Brown communities (Maurer, Harris, & Uscher-Pines, 2014).

Beyond racial disparities, further concerns exist around barriers that impact the general MSM, Transgender, and Queer populations. One such barrier is the lack of culturally competent, sex-positive, and queer-centric care provision, even in areas as diverse as Hell’s Kitchen:

“A number of my friends, as well as myself, if I’m being honest, have reported that their physicians are both unaware that reinfection with MPV is possible and that infections can still occur in people who have been fully vaccinated, and as a result of their knowledge gap are refusing to test MPV lesions.” my friend continued. “There is a paucity of physicians who understand that LGBTQ+ people are going to continue to be sexually active, and this lack of cultural competence leads to our critical healthcare needs going unaddressed.”

What many Americans, and sadly many physicians and healthcare providers, fail to recognize is that healthcare is rarely a “one-size-fits-all” provision model. When we talk about diversity in patient populations, we’re should be talking about more than just racial diversity; we need to include sex and gender diversity, sexual orientation diversity, religious diversity, age diversity, and income diversity. Every patient, whether or not they are aware of them, is impacted by a wide variety of experiences related to their race, age, sex, gender, sexual orientation, and religious beliefs, and those experiences inform when, why, and how they access healthcare services. When providers are not aware of and responsive to those experiences—something that is truly difficult, particularly in areas where the patient-to-physician ratios are astronomically high—the quality of the services being provided suffers.

One way to approach this would be the better (and potentially mandated) incorporation and provision of STD/STI testing, prevention, and care in general practice settings. This would help to normalize the testing, identification, and treatment of STD/STIs in the general population and make seeking services for them less stigmatizing.

Another opportunity that is rarely explored is the provision of STI testing and vaccination services in sex-based venues, such as sex clubs, bath houses, and other venues where intimate contact between individuals is likely to occur. While some physicians—most notably Drs. David Holland and Demetre Daskalakis—have been actively pushing for and engaging in this type of health intervention, it is still a relatively rare type of intervention outside of large urban areas. Moreover, providing these types of services requires additional training for staff, particularly around situational and cultural awareness, as well as developing best practices for interacting with people in these types of settings without negatively impacting the atmosphere and customer bases of those settings.

If we are ever going to eradicate MPV in the United States, we are going to have to do a significantly better job of getting vaccine supplies to those most likely to be impacted and do a better job of overcoming the cultural and hesitancy barriers that exist in those communities. It also means that we have to do a better job of educating the MSM community about the virus and how it’s spread and doing so in a way that is both sex-positive and doesn’t rely upon fear-based tactics to scare people into getting vaccinated or into a monastic lifestyle.

More importantly, we need to come up with a way to incorporate anecdotal reporting of localized outbreaks of MPV in communities into our responses. While the CDC and states may be taking victory laps on their “successful” MPV responses, the reality is that MPV outbreaks are still ongoing and, in many places, are doing so relatively unchecked with little awareness of the disease, its symptoms, its treatments, or how to prevent it.