HIV & Covid-19: A Story of Concurrent Pandemics

On September 20th, Johns Hopkins’ COVID data tracker totaled the “confirmed” (note: not “official”) number of deaths from COVID-19 in the United States to surpass 675,000 – or the estimated number of deaths in the US due to the 1918-1919 H1N1 influenza pandemic (colloquially called the “Spanish flu” because Spanish media were more willing to discuss the pandemic than most other countries). Forbes, STAT, and other large news outlets ran headlines like “Covid-19 overtakes 1918 Spanish flu as deadliest disease in American history” or included statements in their articles like “It was the most deadly pandemic in U.S. history until Monday, when confirmed coronavirus deaths overtook the death toll for the Spanish Flu.”

Which, as Peter Staley pointed out, isn’t factually accurate.

Image: Twitter.com - @peterstaley (Sep 20, 2021) “Um, HIV/AIDS? 700,000 U.S. deaths (and counting), according to the http://HIV.gov https://hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview”

Staley would quickly admit COVID-19 would or already has likely overcome the death toll of HIV in the United States. While I agree with this analysis, I would add “for now”.

The very nature of HIV has made finding a “cure” or vaccine for the virus an oft sought after “holy grail” in pharmaceutical development. While that grail may have been snatched away by the attention COVID-19 is justly generating, this isn’t the first concurrent pandemic HIV has run alongside. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) both refer to the H1N1 influenza outbreak of the 2009-2010 flue season a “pandemic”. The problem of course isn’t just how deadly COVID-19 is, its’ how botched the domestic and global responses have been to the disease.

Viruses, after all, are opportunistic. They have a singular purpose: reproduce. As such, viruses thrive in environments – ecosystems, if you will – that are sorely neglected, lack coordinated responses, and are largely inequitable. But we knew that. We’ve known that with regard to global and domestic health disparities data for decades. As with personal health, emerging, urgent issues in public health reduce our capacity to address existing issues effectively.

As I mentioned in previous blogs, and has been recently noted by the Global Fund, COVID-19 has drastically reduced the efficacy of existing HIV, HCV, STI, and SUD programs. Even still, Global Fund’s report proves a rather interesting point – when meeting the demands of advocates for programs to provide patients with multi-month supplies of medications, meeting people in their own neighborhoods rather than in clinics, and providing at-home testing kits, communities can be activated in care at an exceptional level. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic raging, the needs of the HIV pandemic didn’t stop. And while meeting those needs faltered some (with 4.5% fewer mothers receiving vertical transmission prevention medications, an 11% drop in prevention programming, and a 22% reduction in testing services), in some areas meeting those needs thrived. Global Fund’s report found South Africa was able to increase the number of people receiving antiretroviral therapies by more than three times the baseline, even while fighting on two fronts.

Dr. Sioban Crowley, Head of HIV at the Global Fund, pointed out these program designs are not exclusive to HIV, “If we can keep 21.9 million people on treatment, we can probably deliver them a COVID test and a vaccine.”

Indeed, with the United States’ (and the world’s) response relying heavily on expertise gained in the fight against HIV, one can reasonably ask “If we know how to beat this, why aren’t we…just doing that?”

“That” being what advocates have long asked for: a more dedicated, equitable landscape and adequate support of our public health systems. As with COVID-19, a vaccine won’t “cure” us of HIV if the rest of the world cannot access it. As with HIV, if preventative services, adequate testing, and necessary education are not readily made available to people where they are, we will continue to fail in both fights. If we don’t wish to repeat the losses we’ve already experienced in the fight against HIV, then we cannot keep making the same mistakes of kicking the costs of these investments down the road and maybe, eventually “getting to it”.

As has been said many times through the latest pandemic, “the best time to do the right thing was yesterday. The next best time to do the right thing is today.” It’s time for us to do the right thing and stop allowing backbone public health programs to fall by the wayside in the face of the next emergency. Today, for the next few years, it’s COVID. We don’t need to “wait” for that to end. There’s two pandemics occurring, it’s time we act like it.

Coverages & Pitfalls: Pandemic-Related Health Care Expansion

On September 17th, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced its first complete rule on health care marketplaces (federal and state – HealthCare.gov and SBEs), certain expectations of insurers participating in the health care marketplace, and a slate of other issues. This final rule serves as a regulatory tool amid a raft of information the federal government has provided regarding health insurance coverage during the pandemic.

Portions of the rule were fairly well expected (extending the annual open enrollment period from the slimmed down 45 days the previous administration imposed and revamping the “navigators” program), while other portions sought to more narrowly address – read “stop” or “reverse” – changes from the previous administration (specifically those introduced in 2018 and others introduced on January 19, 2021). The rule also aims to address some pressing concerns from legislators and health care access advocates about affordability of insurance as the economic future of the country remains unstable with the COVID-19 pandemic still wreaking havoc on much of the country.

One September 14th and 15th, the Census Bureau and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), respectively, issued data related to insurance coverage among residents of the United States in 2020 and 2021. The Census data diverged slightly from the HHS data in that the Census data did not show an increase in the number of people enrolled in Medicaid from 2018 to 2020, whereas previously released CMS data had shown a substantial increase (15.6% or about 10.5 million people) in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment from February 2020 through March 2021. A report from the Urban Institute cites potential for the remainder of 2021 to net an additional 17 million people enrolled into the safety net health insurance programs. All of this coincides with the Census data showing the uninsured rate was near static from 2018 to 2020 (8.6% compared to 8.5%).

This is a pretty remarkable comparison, given the pandemic’s effects on the country’s economy. The Census does cite a reported drop in employment related coverage during 2020, with the highest rate of employer sponsored coverage drop occurring among those employed less than full-time. Indeed, the data shows the largest drop in employer sponsored coverage occurred for those at the lowest end of the compensation scale.

Part of why tying together the employment data of the Census and the Medicaid and CHIP enrollment growth data together is to better understand the severe risks to vulnerable people and families as the seeks to wrap up the public health emergency declarations (likely sometime next year). While the administration’s payment rule highlights efforts to keep afloat lower- and middle-income families afloat and insured, the same can’t be said of the lowest-income earners. While the Biden Administration has extended the period for states to return to enrollment recertifications for Medicaid, federal matching funds (a boosted benefit to states during the pandemic) are expected to end on a similar timeframe, giving states some added financial motivation to move through disenrolling current recipients quickly, rather than in a staggered fashion.

While we outlined steps state Medicaid programs and safety net providers could take at the wrap up of the PHE in a blog earlier this month, the Biden Administration must seek even more moves than currently planned, to ensure “back to normal” doesn’t amount to “back to broke” for low-income families across the country.

Veterans Linkage to Care: Perspectives on HIV, Viral Hepatitis, Opioids & Mental Health

Approximately 8 percent of the U.S. population are Veterans, numbering over 18 million Americans with most of them being males and older than nonveterans. But those demographics will change in the coming years, with significant increases in ranks among women and minorities. As a society, we tend to view these men and women formerly in uniform as larger than life figures capable of overcoming almost any odds. The reality, however, is there are numerous ongoing public health challenges faced by Veterans in this country once discharged from the military – among them HIV, Hepatitis C, opioid dependence, and mental health conditions. As a society, don’t we owe it to them to provide the most timely, appropriate linkages to care and treatment?

In 2019, there were 31,000 Veterans living with HIV seeking care within the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system. Additionally, 3.4 million Veterans were eligible for HIV screening. Navigating the VA is challenging enough for our Veterans, but imagine doing so after first being diagnosed with a lifelong, chronic illness like HIV/AIDS? Although no longer a death sentence, Veterans need to learn how to steer living with HIV in what seems like a battlefield of complex bureaucratic systems, simply to start their care and treatment. For Veterans, staying connected to appropriate levels of care continues to be vital for many reasons.

For example, pulmonary hypertension – a blood pressure condition that affects the lungs and heart – is higher among Veterans living with HIV than in veterans who don’t have an HIV-positive diagnosis. What adds an extra level of concern is that Veterans with a CD4 count below 200 are also at higher risk of pulmonary hypertension, including Veterans who have viral loads higher than 500 copies per mL. Pulmonary hypertension within itself is a rare condition but that is exactly the reason why Veterans needs to remain linked to their healthcare providers. Some healthcare providers may not be actively probing for rare conditions like pulmonary hypertension and thus the condition and its possible progression will go largely undiagnosed. This further places into perspective the wide net needed in appropriate, timely HIV care and treatment that goes beyond taking antiretroviral (ARV) medication to achieve viral suppression.

Advances in HIV medicine – namely the introduction of the highly active antiretroviral treatment in 1996 – changed how people can live their lives after an HIV-diagnosis. Whereas people living with HIV who are virally suppressed have the same life expectancy as their non-positive counterparts, they’re also prone to age-related conditions and other co-morbidities, such as the previously discussed pulmonary hypertension. What this also means is that living longer, fuller lives also opens-up the door to emotional distresses.

Newly enlisted service members cycle through intense emotions when shifting from civilian life to the demands of military culture. Post discharge, Veterans can find themselves yet again cycling through acute reactions as they struggle to respond back into the reintegration of the everyday family and civilian life. As a result, studies have shown that incidences of ischemic stroke, the most common type, is more prevalent in Veterans who are HIV-positive dually diagnosed with depression in comparison to Veterans who don’t have a positive diagnosis without depression. This is significant because a common psychological effect of depression is isolation. Without proper linkages to care, so many human pathways of connectivity can begin to become severed. Positive behaviors and patterns begin to change, and this is a dangerous mental state to be in not only as a Veteran struggling with civilian life, but also maintaining the healthy and consistent level of care and treatment that is needed for Veterans living with HIV. It opens the door to poor medication adherence, decreased social networks, and increased likelihood of substance use disorder. These landmines are crucial markers to ensure Veterans living with HIV are kept engaged in their treatment plans. Likewise, all clinicians need to do the same by remembering to evolve with their clients to continue providing them with the services that they need and deserve.

Another silent threat facing both Veterans and nonveterans alike is Hepatitis C (HCV). The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) estimates there are nearly 2.4 Americans living with HCV. It continues to remain a public threat to the general population, but it particularly relevant to address how the silent epidemic is impacting Veterans.

If left untreated, HCV can be fatal because it can lead to cirrhosis of the liver. Veterans experience chronic HCV at three times the rate of the general population, with 174,000 Veterans in active care within the VA system. So, what factors need to be considered by Veterans seeking testing and treatment options for HCV? After all, modern medicine continuously changes the landscape of the available medical treatment options, and the constant reevaluation can be overwhelming. Fortunately, newer HCV therapies have made it a little easier. A qualitative analysis of 29 Veterans who were looking into HCV treatment, 35 total factors were of interest were identified. Of this set of 35 attributes, the top reported were treatment efficacy, physical side effects, new antiviral drugs in the pipeline, liver condition, and psychological side effects.

While the report’s findings aren’t necessarily surprising, how they structured their analysis is important. The Veterans in this study were placed in one of three categories that identified their personal stage of change – which were contemplating treatment, recently declined treatment, and recently initiated treatment. Successful linkages to care involve acknowledging where clients are in the process because it helps to identify and structure a patient centered treatment plan. What is important to remember is that each stage of change is shaped by the personal lived experiences clients are currently experiencing. Some of these subfactors are important social systems that they interchangeably occupy like family, friends, work, religion, and perhaps other various community engagements. All of which can greatly affect the decision-making process when considering treatment. Clinicians across the board need to have a clear picture as to what their client’s value and integrate those value systems into the appropriate levels of care to maximize the effectiveness of their treatment.

This same study uncovered another point of interest that is worth mentioning. When it came to gender, 50% of women compared to 14% of men, reported having concerns with social attributes like stress on partnerships and stigma associated with a disease. Additionally, women also reported concerns about maintaining their privacy within the systems that they occupy. In some ways these results are not surprising given the long history of women being undervalued and overexposed within society. That said, what this does highlight is how the concept and execution of healthcare needs the integration of a vast interpersonal team across a diverse and all-encompassing platform that has the capability to target these pockets of influence.

Healthcare disparities, unfortunately, exist across a wide spectrum within our medical framework and the VA isn’t immune from it. For minority Veterans with hepatitis C, seeking treatment are faced with unique barriers. For example, an HCV-diagnosis is four times more likely among minority Veterans compared to the general population. The VA’s Office of Health Equity (OHE) has done some great work in eliminating health disparities among minority Veterans with HCV, including testing. Testing is made available to all Veterans who are enrolled in the VA; they have treated more than 123,000 Veterans, and successfully cured more than 105,000 Veterans. The VA’s vigorous approach to its mission has been met with great results as race and ethnicity proportions are being treated equally with no population higher than the other. Effective strategies like video telehealth, the use of nonphysician providers, and electronic data tools for timely patient tracking and outreach have allowed the VA to expand their services to better address gaps in care. Work like this is needed across VA systems and local communities to minimize the gaps that are all too often seen in minority groups especially when there are 50,000 Veterans who are undiagnosed for HCV.

Any discussion about linkages to care needs to address the risk association between Hepatitis C and opioids. Since 2010, there have been correlating spikes in both. According to the CDC, HCV cases have nearly tripled between 2010-2015, and during this time the growing use of opioids exploded thanks to OxyContin, Vicodin, morphine, and fentanyl.

Like the general population, substance use disorder can be an inherited experience for Veterans, sometimes exacerbated by the effects of military culture. As a result, 1.3 million Veterans experience levels of substance use disorder. A study by the VA Health System in 2011 indicated that Veterans, when compared to the general population, are twice as likely to experience death from an opioid overdose incident. The biggest leading factor in this is prescription opioid medication and it continues to increase. In 2005, 4 percent of service members reported misusing their prescription medication. Three years later, 11 percent of service members reported the same misuse. The challenge here is that military culture demands a high level of sacrifice, which often comes with potential risk factors like bodily injuries and exposure to traumatic events. Both can be a slippery slope. Physical injury begins to be a major factor almost immediately after enlisting. Service members are pushed daily to exercise and ushered through a series of combat drills that will no doubt include heavy equipment. The body has a great ability to adapt and strengthen itself but like anything else, it has its limits. If this sets the stage for a revolving door of service members in physical pain, the natural course of action would be to provide medication to offset these symptoms. And just like that, accessibility without effective evaluations become the gateway to opioid substance use.

In the same fashion, traumatic events can leave service members feeling disconnected from where they’d like to be both emotionally and physically. In military culture, perception of strength is reality and as such, seeking services for mental health is often challenging for servicemembers as they don’t want to appear weak, so they suffer in silence. But that is exactly the reason why work is needed to change this outcome. Military culture to a very large degree is unwavering. It needs to build soldiers and do that; it needs to condition enlistees. However, it would be beneficial if clinicians and doctors within military culture to incorporate better systems of evaluation when it comes to pain management. This would also need to extend into the various VA systems that service members have access to. Relationships and bonds are obviously built within military culture and their importance may be of great benefit when combating the negative effects of stigma associated with mental health trauma. Community programs can be fostered and guided by various ranking officers to establish a sub community where conversations of real-life experiences demonstrate that a soldier of any rank can be supported by the comrades and communities that they protect.

But accessibility is a two-way street. Clients should have the ability to gain access to healthcare to receive treatment for various medical concerns. Clinicians or outreach programs should be able to have access to community members that need a particular public health service. Syringe services programs (SSP) introduced in the 1980s, have been adopted by the VA system to reduce the harm for Veterans who inject drugs . Veterans who utilize SSP’s can receive substance use and mental health services with the VA including additional services through an SSP program like vaccinations and naloxone, which helps to prevent an accidental overdose. Veterans benefit from community-based programs like this even with the controversies that the program may still carry since its inception. This program has been proven effective in reducing transmission of disease like HIV and Hepatitis C. While this program isn’t stopping the use intravenous drug use, it does open the door for Veterans who may be in a place mentally to accept help. Programs like this are a great hub to access community members and have conversations about recovery services. Like most things in life, addiction is complex involving a multitude of factors that contribute to the addictive behavior. Drugs are the symptom, but the person is the real key to the solution within the equation. Lived experiences matter when looking at public health issues across the board. How people experience live greatly shapes how they decide to show up for it, especially in challenging times. If there are 343,000 Veterans who use illicit drugs, then effective and targeted programs need to be in place not only at VA systems but also in their surrounding communities. One of the great aspects of SSP programs is that it targets Veterans by how they are currently living with a substance use disorder, and while strengthening community engagement through public service.

Military culture and trauma are often associated with one another, but it isn’t always linked to deployment. That said, combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is quite prevalent among active-duty service members, as well as Veterans. For service members nearing active-duty discharge, a diagnosis of PTSD may change the status of their discharge, greatly affecting the outcome of receiving services from the VA. The term “bad papers” is used within military culture to signify that a Veteran has been discharged unfavorably. A status discharge of other than-honorable is essentially the kiss of death because it means that a Veteran will not be able to access services through the VA. What is interesting about this status is that it is given for felonies, those absent without official leave (AWOL), desertion and Veterans with drug offenses. The issue then becomes the consequent behaviors of Veterans struggling with PTSD who turn to substance use to cope and who then also begin to have behavioral changes which affects level of performance on all fronts. Veterans carry an immense sense of pride for their service, and rightfully so. They have stepped in roles that most people don’t have the courage to do so. As an evolving clinician, seeing a Veteran struggle with PTSD due to the natural climate of what their duty demands of them, and then being shut out of benefits that are crucial to their mental health is just unacceptable. Discharge review boards really need to reconsider the criteria for evaluating Veterans who suffer from traumatic events. Not doing so sends a message that devalues the sacrifices that they have made which then perpetuates the stigma associated with their discharge status, but also reinforces the negative outlook of mental health within military culture. Veterans should not have to suffer in silence for enduring what was demanded of them and then be casted aside because their organization feels that their value has expired.

In 2016, over 1.5 million of the 5.5 million Veterans who entered the VA hospitals, had PTSD or other mental health diagnosis. That’s a staggering number especially when you consider the constant influx of Veterans who are returning home from deployment. Compared to the general population, suicide death rates are higher in Veterans, and furthermore female Veterans have a suicide rate of 35 per 100,000. Mental health services within the VA system have been on ongoing challenge as they try to meet the demand that Veterans need for crisis-intervention. As it is, mental health services are expensive for nonveterans, and even those who are insured may not have the adequate coverage to seek mental health services during a crisis episode. For Veterans returning home experiencing a mental health condition, this is disastrous as communities and VA systems both struggle to provide crisis stabilization and interventions. As a result, many Veterans experience depression on top of another mental health diagnosis like PTSD. Homelessness in Veterans is also increasing with more than 107,000 Veterans who are displaced. All of this is a perfect storm for a Veteran to feel like all hope is lost and consider suicide and reports reflect that with 21 Veterans, on average, dying of suicide every day. In society, there is a lot of talk about how all human beings are deserving of human equity. Human equity should include the ability to access mental health services (and healthcare as a whole), and the capability to navigate healthcare systems by having the support of organizations, communities, and effective public policy.

The military culture’s sphere of influence is completely different from civilian life. It is a complex system demanding everything military personnel can give, but it can often fall short when the time comes to giving back to Veterans. The sad truth is, Veterans often confront too many barriers when attempting to access appropriate timely care and treatment. It isn’t a secret that mental health disorders and other numerous challenges, such as substance use disorder, stem from military service-related experiences. Yet, systems in place for Veterans are inadequately structured to meet the numerous public health issues confronting Veterans and, subsequently, their families. Accessibility to healthcare services, including mental health, needs to encompass a wide net of effective policies and programs but also infused with the knowledge of how Veterans occupy the various systems that they live in and are affected by them. Too often in healthcare, clients are evaluated solely based off a diagnosis and without ever including who they are and their lived experiences. These are large, missed opportunities for clinicians to home in on invaluable information that can help formulate more effective treatment plans in conjunction with innovative and effective public policy. Hubs like VA systems are a great resource for Veterans, but we need to make sure the avenues of accessibility remain open for all Veterans that are eligible. It is very rare that a solution to a problem ever stands alone, and this perspective should continue to be a driver as community engagement and expansion in healthcare accessibility is needed. Veterans answered the call of duty without hesitation so now we must not drag our feet when Veterans need us the most in a war that poor public policy, lack of community programs and military culture has waged on them.

References:

Belperio, A,. Korshak,L., & Moy, E. (2020). Hepatitis C Treatment in Minority Veterans. Office of Health Equity. Retrieved online at https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Hepatitis_C_Treatment_in_Minority_Veterans.asp

Burek, Gregory, M.D. (2018). Military Culture: Working With Veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. Retrieved online at https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.130902

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2018). CDC Estimates Nearly 2.4 Million Americans Living with Hepatitis C. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved online at https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2018/hepatitis-c-prevalence-estimates-press-release.html

Duncan, M. S., Alcorn, C. W., Freiberg, M. S., So-Armah, K., Patterson, O. V., DuVall, S. L., ... & Brittain, E. L. (2021). Association between HIV and incident pulmonary hypertension in US Veterans: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity.

HepMag (2019). Veterans and Hepatitis C. Retrieved online at https://www.hepmag.com/basics/hepatitis-c-basics/veterans

Hester, R. D. (2017). Lack of access to mental health services contributing to the high suicide rates among veterans. International journal of mental health systems, 11(1), 1-4.

Maguire, Elizabeth (2021). Providing clean syringes to Veterans who inject drugs. VAntage Point (Blog). Retrieved online at https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/89943/providing-veterans-inject-drugs-clean-syringes/

Military Officers Association of America blog (2017). Veterans and Opioid Addiction. Retrieved online at https://www.moaa.org/content/publications-and-media/features-and-columns/health-features/veterans-and-opioid-addiction/#.YNxcrmTZy_0.twitter

Pebody.,R. (2018). Life expectancy for people living with HIV. AIDSmap. Retrieved online at https://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/life-expectancy-people-living-hiv

Schultz, Jennifer (2017, November 10). Veterans By the Numbers. The NCSL Blog. Retrieved online at https://www.ncsl.org/blog/2017/11/10/veterans-by-the-numbers.aspx#:~:text=There%20are%2018.8%20million%20veterans%20living%20in%20the,rise.%20Veterans%20tend%20to%20be%20older%20than%20nonveterans

Sico, J. J., Kundu, S., So‐Armah, K., Gupta, S. K., Chang, C. C. H., Butt, A. A., ... & Stewart, J. C. (2021). Depression as a Risk Factor for Incident Ischemic Stroke Among HIV‐Positive Veterans in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(13), e017637.

Sisk, R. (2021). ‘Dirty, Embarrassing Secret:’ Veterans with PTSD Struggle to Shed Stigma of Bad Paper Discharges. Military. Military.com. Retrieved online at https://www.military.com/daily-news/2021/04/21/dirty-embarrassing-secret-veterans-ptsd-struggle-shed-stigma-of-bad-paper-discharges.html

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Veteran Adults. Retrieved online at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt31103/2019NSDUH-Veteran/Veterans%202019%20NSDUH.pdf

U.S Department of Veterans Affairs, (2020). Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) - VA IS THE LARGEST SINGLE PROVIDER OF HIV CARE IN THE UNITED STATES. Fact sheet. Retrieved online at https://www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/HIV-program-factsheet.pdf

Wisely, Rene (2018). Why Are Hep C Infections Skyrocketing? Opioid Abuse to Blame. Michigan Medicine. Retrieved online at https://healthblog.uofmhealth.org/hep-c-infection-and-drug-abuse

Zuchowski, J. L., Hamilton, A. B., Pyne, J. M., Clark, J. A., Naik, A. D., Smith, D. L., & Kanwal, F. (2015). Qualitative analysis of patient-centered decision attributes associated with initiating hepatitis C treatment. BMC gastroenterology, 15(1), 1-10.

Biden Administration’s Healthcare Future is One of Promise & Peril

Last month, the Biden Administration issued a press release outlining a look toward the future of American health care policy. Priorities in the presser include ever elusive efforts around prescription drug pricing and items with steep price tags like expanding Medicare coverage to include dental, hearing, and vision benefits, a federal Medicaid look-alike program to fill the coverage gaps in non-expansion states, and extending Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies enhancements instituted under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in March. Many of these efforts are tied to the upcoming $3.5 trillion reconciliation package.

President Biden renewed his call in support of the Democrats effort to negotiate Medicare prescription drug costs, enshrined in H.R. 3. Drug pricing reform has been an exceptional challenge despite relatively popular support among the voting public, in particular among seniors. The pharmseutical industry has long touted drug prices set by manufacturers do not represent the largest barriers to care and mandating lower drug costs would harm innovation and development of new products. Indeed, for most Americans, some form of insurance payer, public or private, is the arbiter of end-user costs by way of cost-sharing (co-pays and co-insurance payments). To even get to that point, consumers need to be able to afford monthly premiums which can range from no-cost to the enrollee to hundreds of dollars for those without access to Medicaid or federal subsidies. The argument from the drug-making industry giants is for Congress to focus efforts that more directly impact consumers’ own costs, not health care industry’s costs. Pharmaceutical manufacturers further argue mandated price negotiation proposals would harm the industry’s ability to invest the development of new products. To this end, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released a report giving some credence to this claim. The CBO’s report found immediate drug development would hardly be impacted as those medications currently “in the pipeline” would largely be safe, but a near 10% reduction in new drugs over the next 30 years. While new drug development has largely been focused on “personalized” medicine – or more specific treatments for things like cancer – implementing mRNA technology into vaccines is indeed a matter of innovation (having moved from theoretical to shots-in-arms less than a year ago). With a pandemic still bearing down on the globe, linking the need between development and combating future public health threats should be anticipated.

The administration’s effort to leverage Medicare isn’t limited to drug pricing. Another tectonic plate-sized move would seek to expand “basic” Medicare to include dental, hearing, and vision coverage. Congressional Democrats, while generally open to the idea, are already struggling with timing of such an expansion, angering Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) by suggesting a delay until 2028. While any patient with any ailments related to their oral health, hearing, and vision will readily tell you these are critical and necessary coverages, even some of the most common of needs, the private health care insurance industry generally requires adult consumers to get these benefits as add-ons and the annual benefit cap is dangerously low (with dental coverage rarely offering more than $500 in benefit and vision coverage capping at one set of frames, both with networks so narrow as to be near meaningless for patients with transportation challenges). While the ACA expanded a mandatory coverage for children to include dental and vision benefits in-line with private adult coverage caps, the legislation did nothing to mandate similar coverages for adults and did not require private payers to make access to these types of care more meaningful (expanded networks and larger program benefits to more accurately match costs of respective care).

The other two massive proposals the Biden Administration is seeking support for, more directly impact American health care consumers than any other effort from the administration: maintaining expanded marketplace subsidies and a federal look-a-like for people living in the 12 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion provisions. The administration has decent data to back this idea, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report showing a drop in the uninsured rate from 2019 to 2020 by 1.9 million people, largely attributed by pandemic-oriented programs requiring states to maintain their Medicaid rolls. The administration and Congressional Democrats are expected to argue subsequently passed legislation allowing for expanded subsidies and maintained Medicaid rolls improved access to and affordability of care for vulnerable Americans during the pandemic. As the nation rides through another surge of illness, hospitalizations, and death from the same pandemic “now isn’t the time to stop”, or some argument along those lines, will likely be the rhetoric driving these initiatives.

Speaking of the pandemic, President Biden outlined his administration’s next steps in combating COVID-19 on Thursday, September 9th. The six-pronged approach, entitled “Path out of the Pandemic”, includes leveraging funding to support mitigation measures in schools (including back-filling salaries for those affected by anti-mask mandates and improving urging the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] to authorize vaccines for children under the age of 12), directing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to issue a rule mandating vaccines or routinized testing for employers with more than 100 employees (affecting about 80 million employees) and mandating federally funded health care provider entities to require vaccination of all staff, pushing for booster shots despite the World Health Organization’s call for a moratorium until greater global equity in access can be attained, supporting small businesses through previously used loan schemes, and an effort to expand qualified health care personnel to distribute COVID-19 related care amid a surge threatening the nation’s hospitals ability to provide even basic care. Notably missing from this proposal are infrastructure supports for schools to improve ventilation, individual financial support (extension of pandemic unemployment programs or another round of direct stimulus payments), longer-term disability systems to support “long-COVID” patients and any yet-unknown post-viral syndromes, and housing support – which is desperately needed as the administration’s eviction moratorium has fallen victim to ideological legal fights, states having been slow to distribute rental assistance funds, and landlords are reportedly refusing rental assistance dollars in favor of eviction. While the plan outlines specific “economic recovery”, a great deal is left to be desired to ensure families and individuals succeed in the ongoing pandemic. Focusing on business success has thus far proven a limited benefit to families and more needs to be done to directly benefit patients and families navigating an uncertain future.

President Biden did not address global vaccine equity in his speech, later saying a plan would come “later”. The problem, of course, is in a viral pandemic, variant development has furthered risks to wealthy countries with robust vaccine access and threatened the economic future of the globe.

To top off all of this policy-making news, Judge Reed O’Connor is taking another swing at dismantling some of the most popular provisions of the ACA. Well, rather, yet another plaintiff has come to the sympathetic judge’s court in an effort to gut the legislation’s preventative care provisions by both “morality” and “process” arguments in Kelley v. Becerra. The suit takes exception to a requirement that insurers must cover particular preventative care as prescribed by three entities within the government (the Health Resources Services Administration – HRSA, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – ACIP, and the Preventative Services Takes Force – PSTF), which require coverage of contraceptives and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with no-cost sharing to the patient, among a myriad of other things – including certain vaccine coverage. By now, between O’Connor’s rabid disregard for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans and obsessive effort to dismantle the ACA at every chance he can – both to his own humiliation after the Supreme Court finally go their hands on his rulings – Reed O’Connor may finally have his moment to claim a victory – I mean – the plaintiffs in Kelley may well succeed due to the Supreme Court’s most recent makeover.

As elected officials are gearing up for their midterm campaigns, how these next few months play out will be pretty critical in setting the frame for public policy “successes” and “failures”. Journalists would do well to tap into the expertise of patient advocates in contextualizing the real-world application of these policies, both during and after budget-making lights the path to our future – for better or worse.

A Different Booster: HBV Vaccines among PLWHA

Because of the shared transmission vectors between HIV and Hepatitis B (HBV), the rate of co-infection is about 10% in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). As a result, people living with HIV (PLWHA) are more likely to experience adverse health impacts including cirrhosis and certain types of liver cancers. A small study conducted in Chile took a look at the recommended HBV vaccine schedule among adults living with HIV and HBV antibody uptake and potentially finding cause for a “high dose” fourth shot to be added into the series for PLWHA.

A giant asterisk belongs on the study’s findings, labeled “deserves further study consideration”. Despite being double-blinded, the study’s greatest weakness included participant pool size (right around 100 participants) and clinical selection criteria (which remains an issue in clinical trial work, generally speaking). In order to be considered for the study, participants generally had to present with an undetectable HIV viral load and no other comorbidities, ruling out application of the resulting data to most PLWHA and especially most long-term survivors or people experiencing barriers to care or medication adherence concerns – or those most likely to be impacted by HIV and HBV co-infection.

The study sought to examine the need for revaccination among PLWHA. Of note, the CDC’s “Pink Book” on HBV does not recommend “boosters” unless a particular “low” threshold of HBV antibodies is met, nor does the publication recommend for routinized serological testing among people who have previously received a vaccine. Therein lies a program and policy problem. We’ll get to that in a moment.

As a result of selection bias favoring those with more ideal circumstances, few participants dropped out of the trial. The study itself found that a fourth and “stronger” dose of vaccine improved antibody responses among people with “well controlled” HIV with an improved HBV antibody response from 50.9% in the low-dose arm of the study to 72% among the high-dose arm of the trial. After a one-year follow up, 80% of participants of the high-dose arm still had sufficient antibody titers, whereas only 39% of the standard-dose arm still had sufficient antibodies for protection.

While Ryan White and CDC funded clinical care programs for PLWHA require HBV monitoring and vaccination efforts as part of their grant funding, few entities necessarily do and almost no private providers do. Federally-funded providers may screen upon intake or initial labs but maintenance screening is not a priority in terms of clinical data collected on a given patient. Even on-site audits from these funders can sometimes look like reviewing particular case files and discussing details but the HBV conversation is not pressing. Rather, a review of intake data can suffice depending on the clinical auditor/consultant (site-visits and audits are often conducted under the supervision of the funding agency but only actually audited by consultants, including staff from other funded clinics).

Public funders aiming to end HBV and the unjust circumstances in which PLWHA are not educated by their providers on the other risks to their health should shift some focus to emphasize the need for preventative care – especially vaccines. Provider education for these publicly funded clinics should include the need to routinize HBV antibody monitoring not just as a concern on behavioral risk factors continuing in a client’s life but because HBV immunity is clearly not necessarily a given, regardless of prior vaccination history.

While the study suggests the need for investigating further, with regard to efficacy of HBV vaccines among PLWHA, the larger question - given the nation-wide rush for another vaccine (and boosters) - creating more robust standards of care among a population known to have immunological “memory-loss” due to the particular cells “attacked” by HIV seems to be in order. Part and parcel to that is tying this level of necessary education to funding and licensure could improve the quality of care PLWHA receive, especially those of low-income and otherwise marginalized identities.

Amid HIV Outbreaks, Covid-19 Fractures Existing Public Health Efforts

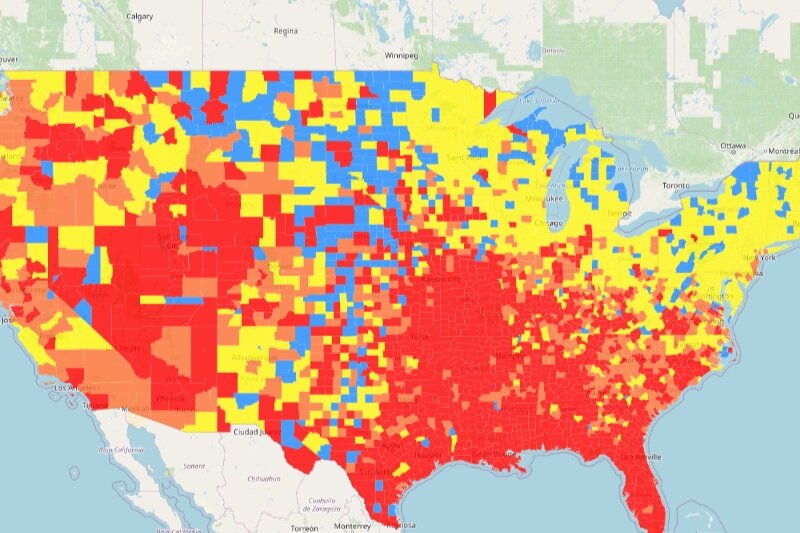

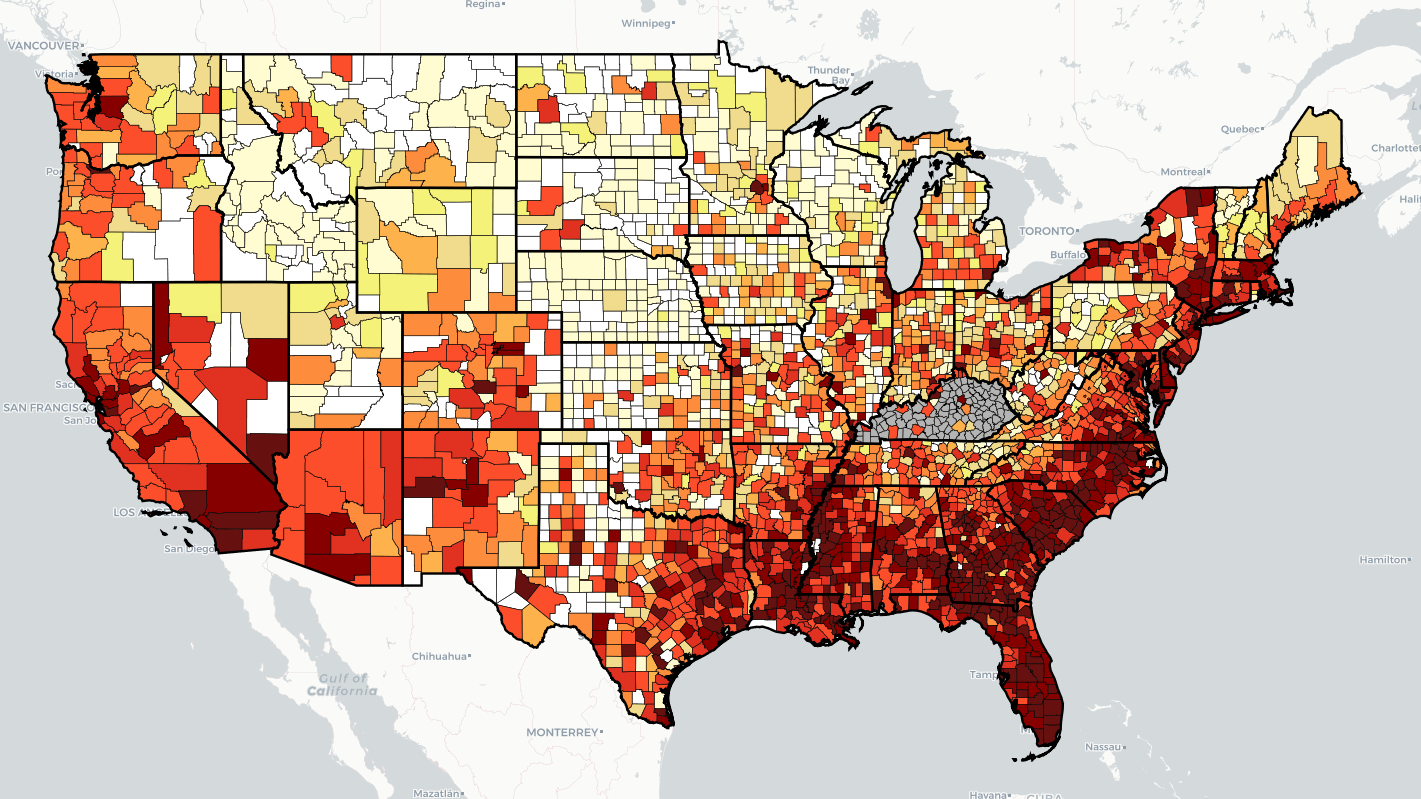

“Every health disparity map in the United States is the same,” Alex Vance, Senior Director of Advocacy and Public Policy at the International Association of Providers in AIDS Care, has repeatedly stated when discussing the COVID-19 pandemic and the very real risks of “back sliding” in our moderate advancements in the United States’ effort to End the HIV Epidemic. There’s no better way to demonstrate this than by showing you.

As another “wave” of Covid-19 ravages the country, increasing cases, hospitalization rates, and eventually deaths, existing public health needs around HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections continue to be strained, pushed to the back burner and most often in geographic areas where we need to be able to juggle more, not less; particularly across the South. Unlike Covid-19 outbreaks, which receive fairly immediate attention in terms of reporting and response, HIV outbreaks can and do often take a year or more to notice and begin action to address. While there’s concern about juggling the demands of addressing concurrent pandemics, some (certainly not all) of this reporting and response is beginning to speed up with regard to HIV.

West Virginia’s Kanawha County HIV outbreak is considered a 2020 outbreak, though just recently received a report from the Center’s for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) on next steps and recommendations to address. Despite these recommendations including supporting syringe exchange programs and community-based services, local officials continue a politically oriented response by seeking to limit the support of syringe exchange programs, threatening their ability to operate and aid in addressing the needs of the local community. Another outbreak in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula was identified in July of this year, with rural Kalkaska County reporting a higher rate of new HIV diagnoses than even Detroit. Kalkaska County is so similarly situated to Scott County, Indiana, it’s striking. Louisville, Kentucky has reported almost as many new HIV diagnoses in the first half of 2021 as the area does annually. And Duluth, outside of Saint Louis, Minnesota, joined neighboring Hennepin and Ramsey Counties with declared outbreaks tied to 2019 and 2018, respectively.

What’s important to note about 2020’s marked reduction in HIV screenings is not just the delay in newly diagnosing people living with HIV, but the lack of ability to link people to care upon diagnosis, beginning antiretroviral therapy and taking steps to reduce the person’s viral load. With at-home testing being the substitute offering, linkage to care and counseling for people self-testing may be hampered according to some concerned advocates. Achieving viral suppression also reduces the possibility of transmitting HIV by way of sexual contact to zero (“Undetectable = Untransmittable”) – creating a process where people living with HIV are not just a patient group needing identification, but play a critical role in preventing new transmissions.

In reviewing the possibilities of delayed care and delayed screening, public health officials and advocates should remember a new diagnosis is not necessarily indicative of a new transmission. A potential problem in and of itself, in assessing Covid-19 disruptions in screening and care, is the possibility of a “bottle neck” of new testing revealing new HIV diagnoses which otherwise might have been identified in the previous year if not for stay-at-home orders, education and public awareness campaigns, and community health care providers having had to take a step or shift gears entirely from HIV to Covid-19. It will take years for us to truly understand the breadth and reach of Covid-19 on the world’s only concurrent pandemic, even in the “most advanced country in the world”.

What can already be well-appreciated and should be well-understood is we cannot afford to keep asking community-based health care providers and community partners in combatting the domestic HIV epidemic to keep sacrificing HIV screening and linkage to care in order to address Covid-19. What must be prioritized is funding, programming, training, and most importantly hiring of new talent in addition to existing programs in order to address both sets of needs.

As I summarized in a previous blog, capacity has been breached, we cannot afford to keep asking public health to do more with less and expect to succeed in addressing Covid-19, HIV, viral hepatitis, STIs, or the opioid epidemic.

Post-PHE: Continuity in Care for Vulnerable Populations is Critical

On July 20th, the United States extended its existing declaration of Public Health Emergency (PHE) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic for 90 days. Previously, the PHE had been renewed 6 times under the previous and current administrations. The PHE declaration may be extended past October 20th, 2021, should the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Xavier Becerra, renew the declaration.

Pandemic response and relief funding from the federal government has come with strings attached in order to ensure those funds are directed toward those who need the help the most. Most of these strings operate as both “stick and carrot” and one of the more interesting “carrots” was the increase of federal dollars supporting state Medicaid programs for the trade-off of maintaining those Medicaid rolls, temporarily ceasing redetermination and reenrollment activities, allowing people to remain on Medicaid rolls through the PHE without having to go through the usual hoops of proving their eligibility on a more regular basis.

While the previous administration directed states to anticipate a return to usual work after the PHE, engaging in a massive redetermination effort inside of 6 months of the PHE ending, earlier this month, the Biden administration informed states that redetermination period would be extended to 12 months in order to avoid an artificial “bulge” of redeterminations and eligibility checks and, ultimately, a potential annual cycle of concentrated renewals in a short window of time. It’s important to remember, as we discuss Medicaid redetermination, rules vary by state and those disenrolled during redetermination are not necessarily ineligible, they may merely not have had an opportunity to respond to a request for information for a variety of reasons.

The guidance from the Biden Administration speaks directly to this issue, stating states should consider providing a “reasonable” amount of time for clients to provide additional information for redetermination. The administration’s idea of a reasonable amount of time is 30 days. Louisiana, as an example, typically only allows for 10 days from the date in which a paper letter has been mailed to a Medicaid recipient for that same recipient to respond. If the recipient is ill, needs to gather supporting evidence from multiple sources, the mail is slow, or any number of factors outside of their control, they may be unceremoniously disenrolled. A mass redetermination effort in a shortened period of time runs a significant risk of disenrolling otherwise eligible clients but for a process that leaves less than no room for delay or mistake. Indeed, a 2019 report from Louisiana’s Health department found that 85% of eligibility cases were closed for a lack of response to a request for information. Louisiana isn’t alone in these burdensome processes, which on the surface, appear to be aimed at discouraging residents from accessing Medicaid by way of process burden.

Overall, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) saw an increase in enrollment starting in March 2020 and continuing today, though with a slower pace, after at least 2 years of decreasing enrollment, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation report. The same report shows Medicaid program enrollment has increased by about 20% - to about 81 million people – since February 2020 and expects many remain on Medicaid and CHIP rolls as a result of economic uncertainty and instability.

At the intersection of Medicaid, COVID, and economic uncertainty are vulnerable communities, experiencing some of the highest rates of viral hepatitis and HIV. A tertiary benefit of Medicaid’s maintenance of coverage through the public health emergency is those living with viral hepatitis and HIV have been able to more readily seek coverage and care. The problem is a complete lack of “warm hand-off” between Medicaid programs and other assistance programs clients could be significantly advantaged by. Particularly, because of the overlap in intersections of oppression and risk (which some more readily recognize as “social determinants of health”), AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, Ryan White services, and other support services (both publicly and privately funded) are critical tools in our public health safety net.

Tossed off the front burner of public health efforts, “Ending the HIV Epidemic” activities have still been chugging along throughout the COVID-19 crisis. The only other concurrent running pandemic didn’t suddenly go away because COVID-19 came rushing to the forefront of our public health efforts. One of the things these other support programs struggle the most with is ensuring the public (and even health department and hospital case managers) know these programs exist. State Medicaid programs, AIDS service organizations, Ryan White Clinics, and all other safety net programs should be coordinating for the shift in patient load across appropriate programs now. These planning activities should not wait until the midnight hour. For county run COVID-19 testing sites and vaccination sites should be providing information to every, single person seeking a vaccine about available programming to meet the needs of community members. From rental assistance to food pantries to ADAPs, programs already reaching communities and families are the most ideal for starting the process of maintain care after the PHE ends. That starts with passive efforts like brochures and should continue with more active efforts, like engaging a state’s 311 information system with linkage to care tools, and more active still by employing navigators at the Medicaid level to assist clients in finding services, should those clients find themselves ineligible post-PHE.

While we’re not there yet (and it make take significantly longer than any of us like due to a lack of equitable global vaccine access and variant development), advocates, states, service providers, and patients should be planning for what comes next when the PHE eventually comes to an end. We cannot afford to lose people to care at this critical juncture.

Degrees of Separation: Social & Spatial Networks of HIV & HCV

In 1929, Frigyes Karinthy posited a theory many of us might attribute to Kevin Bacon: everyone on the planet is but six degrees of separation (or less) from one another. Depending on how one would measure a connection, that metric is likely far less than it was in 1929. Beyond social media marketing, connecting these networks of friends and friend-of-friends has been pretty important to the concepts of “partner testing and notification” utilized by disease intervention specialists to disrupt chains of transmission in terms of STIs and HIV. What’s been less well understood is the geographic relationship between areas experiencing outbreaks or “clusters” or the specific venues in which transmission occurs – social-spatial networks.

A study performed in New Delhi sought to better understand the relationship between social circle and gathering venue among “hard to reach populations” homeless people and/or, particularly, people who inject drugs. Originating recruitment from within community, asking community to propel recruitment, and paying particular attention to the “mutuals” between otherwise unconnected participants, the researchers sought to better understand the relationship of “risk” of transmission not just in behavior or large geographic area but in specific places in which specific behaviors are part of the culture – the community standards, if you will - of that venue. Researchers found 65% of participants had HCV antibodies, of which 80% had an “active infection” and most were unaware of their HCV status. Similarly, of those participants living with HIV, 65% were directly connected with another participant living with HIV. Researchers did not specify these connections to be causative – those connected did not necessarily transmit either virus to one another. Further, researchers found partaking at the most popular venue was associated with a 50% greater likelihood of a participant having an HIV or HCV diagnosis. Even if a participant did not access the most popular venue, if they associated with someone who did, their likelihood for being diagnosed with HIV or HCV was 14% higher. And the more degrees of separation a participant had from someone who accessed the most popular venue, the less the likelihood of a diagnosis.

The researchers conducting the study were hoping to identify methods of understanding that would allow for effective interventions that reach beyond the individual level. Can group behavior be influenced beyond recruitment and toward changes? Can harm reduction strategies or housing programs find greater efficacy, a better stretch of our dollars, by better understanding where these networks exist and how they operate?

Or is this association merely a by-product of sharing certain characteristics society has deemed unworthy of care? Those social ills that drive disparities in health and poverty and addiction may also drive those experiencing these harms of bias and negligence to seek a social network that at least understand their struggles. To be a little less alone in these struggles.

As is the nature of most things, a better understanding of behavior doesn’t always lend itself to building positive interventions. The same ability to navigate networks in areas where people living with HIV are discriminated against and people who inject drugs can easily be criminalized, rather than connecting to care. With molecular surveillance generating the ire of HIV advocates over fear of this kind of detailed knowledge being used by law enforcement, advocates should also keep a keen eye on how networks may be weaponized as well.

Understanding the spatial relationship within a social network could be a powerful public health tool that shifts our focus from individual intervention to far more meaningful interventions, so long as we can keep the focus of this type of research and the information gathered from it squarely aimed at building up the “public” part of public health rather the continuing to push the responsibility of public health on individual behavior.

Potentially Powerful Tools: A Vaccine in the Fight Against HCV

In 1989, Sir Michael Houghton helped discover the Hepatitis C Virus. Last year, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this same discovery. Now, he’s aiming to create a vaccine against the virus.

Just a few weeks ago, Houghton announced an effort at the University of Alberta’s Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute that could have a adjuvanted recombinant vaccine ready for global deployment by 2029. Both new mRNA and viral vector vaccines, used in the COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized by the Food and Drug Administration under an emergency use authorization, have the potential strength to produce multiple kinds of antibodies, solving a long-held problem in the search for an HCV vaccine.

A couple of words of caution: A recent study, using two viral vectors, while successful producing HCV specific T-cells, failed to prevent chronic HCV infection. The last decade has seen several attempts at developing an HCV vaccine but few have made it to human trial, specifically because of evasive properties of the virus’ genotypes to behave differently or escape the body’s natural defenses.

If Houghton and his team are successful, a 2029 launch would likely still have much of the globe well behind the World Health Organization’s 2030 goals but adding a clear, definitive prevention tool stopping chains of transmission would, in theory, help countries playing “catch-up”. With complications from Hepatitis C killing more than 400,000 people annually – and possibly more in the coming years due to COVID-19-related disruptions in care – a vaccination effort could very easily save millions of lives and save billions in public health and health care funding. Houghton suggested Canada alone could see a reduction in HCV-related costs of 98%, or $20 million as opposed to $1 billion – annually due to the high costs of direct acting agents, which are the current gold standard in HCV care and can be curative.

However, if global access to COVID-19 vaccine difficulty and notable vaccine distrust and failure to uptake have taught us anything, having the technology is not the same as having the technology. COVID-19 doesn’t appear to be slowing down, despite recurrent waves, and supply demand on shared vaccine ingredients could find HCV deprioritized.

Additionally, there’s other potential complications to consider. While the United States has seen an increase in Hepatitis B vaccine acceptance, in part thanks to an infant vaccination schedule inclusive of HBV, a study published last year found waning immunity over the years post-vaccination. Now, the CDC’s information page does not recommend HBV boosters and technology may differences may naturally boost efficacy of vaccines but anything that needs additional follow up, like multi-stage vaccines or boosters, are always prone to follow-up failures. And – yet again – COVID-19 provides an excellent case study in this (and all other hidden asterisks). With “anti-vax” sentiments rising at exceptional rates, especially associated with “new” technologies, adding yet another vaccine to the schedule may find barriers in acceptance other common vaccines haven’t run into, at least not on this scale.

Nevertheless, a successful HCV vaccine that answers the challenges of the virus, the conspiracy, and the supply would be a game-changer (to use an unfortunately over-used phrase).

If advocates and policy makers have learned anything, being well prepared for an ever-changing environment in terms of technological advancements, the advancement of anti-science sentiments, and a whole host of other challenges is to our benefit. Analyzing the years between now and, hopefully, 2029, perfecting routine vaccination programs and ensuring actual global equity in access and distribution are critical to making sure this kind of discovery doesn’t go to waste.

Jen’s Half Cents: The Trauma of Advocacy

Author’s note: This blog will not be giving any identifying information, screenshots, or links to provider or advocate comments. As the focus of this blog is a need to acknowledge the traumatic nature of working in public health and advocacy, protecting the identities and personal spaces of these heroes is of the utmost importance.

In April of this year, a friend I’ve worked closely with on a variety of personal and professional levels wrote me: “So…I’ve quit my job and left the field.”

They had spent years working for a health department funded entity serving both urban and rural areas, doing outreach, contact tracing, care and coverage navigation, advocating for clients with providers, for providers with administrative management – the full gamut of public health activity, specifically around HIV and STIs. Last March, they were sidelined to COVID work, face-to-face, often without protective equipment, lacking time off, enough staffing support, and more. Everything everyone else went through as COVID gripped the nation with the most stringent mitigation efforts. Over the summer they would be tasked with pulling “double duty” between COVID contact tracing efforts and HIV and STI work.

This story is not unique.

While higher profile exits from the field of public health have gotten some attention, as evidenced by CNN’s coverage in May on more than 250 public health officials having quit, resigned, been fired, or retired, those that take on the daily tasks of providing care within communities haven’t gained the attention they deserve. In January, the National Coalition of STD Directors published their “Phase III” survey of state STI programs and the findings were startling – every, single published comment discussed the issue of burnout among disease intervention specialists, data managers, and other client-facing staff. As the so-called Delta Variant of SARS-CoV-2 grips the nation in now a noted “fourth wave”, these human resources making the very body of public health haven’t been replenished. Many providers, advocates, community members, survivors, loved ones of those lost to COVID, some elected officials, and those at greatest risk of severe COVID complications or loving those who cannot yet access vaccines have taken to social media to voice their frustration with the state of the nation’s response to COVID-19.

For HIV/AIDS advocates, this isn’t new. We’ve spent four decades being ignored or actively discriminated against, having our stories stolen from us and mutilated in efforts to demonize us, our vulnerabilities and very disease state criminalized – used as justifications for denying us basic freedoms and access to the very care that keeps us and our loved ones alive. We’ve watched promises made, lofty goals announced, and the dollars behind those goals go unused due to lack of flexibility and then usurped to put children in cages and concentration camps, those dollars used to rip children from their parents, sometimes right before their eyes. People living with HIV accessing Ryan White programs are asked to detail to case managers intimate and personal aspects of their lives they may never share with other people. The same case managers who are over worked and underpaid and can’t be provided the supports they need in order to make clients feel like the ears and eyes prying in their lives actually care.

Yet and still, these same voices, these same lives and experiences are those relied upon to move legislators and policy makers, and beg and plead for changes that would reduce barriers to care for us and other people. There is not a single advocate I know, personally, who has not run into a barrier to care or system failure or – frankly – a bigot abusing politics or process who has not turned around and fought with every breath to ensure those harms are ended. “I will do everything I can to make sure no one ever has to go through what I went through.” There is a love in this sentiment that cannot be measured. It fills you up – it fills me up – from your gut to your chest, it becomes the wind at your back and that love inspires and sustains…for a while. That love stands in stark contrast to the politicized and polarized response to COVID-19 mitigation efforts and vaccination campaigns where frustrations run up against conspiracy theories and near sociopathic adherence to contrarian conflict.

We don’t talk about what it is, the personal cost, to retell our stories time and again. We don’t talk about the nature of purposely reengaging our traumas in order to advocate for the world around us. There’s a fear that runs quiet in the background when some decides to change their path or step back from advocacy. That fear often sounds like a hushed phone call, “Am I a bad person for not being up for this?” All that fear compounds with the daily stress of paying bills or commuting or caring for family or going to school so you can be heard with more legitimacy or…or…or….

That piece is the emotional labor of survival.

Advocacy and public health are not for the faint at heart. And….

Those entities, governmental and private, funding care and advocacy, regardless of space – be it oncology, HIV/AIDS, STIs, substance use recovery – need to consider these costs when evaluating awards. When compensation for these stories or “community engagement” often tops at twenty dollars an hour, funders are telling those with the courage and voice to share those stories that our years of trauma – the very expertise of “lived experience” or existing at the intersections making up your consumer base – is worth less than the average cost of your tank of gas. Supporting communities means supporting a living wage, supporting operations costs, supporting expanding staffing, supporting entities with mental health days as part of leave policies. Supporting effective advocacy and efficient public health means supporting the very humanity behind these efforts.

WHO Hepatitis C Elimination Goal Slipping Away

In 2016, shortly following the introduction of direct acting, curative agents, the World Health Organization set a goal of global elimination of HCV by 2030. At the time, it was an ambitious but potentially achievable goal. The WHO, much like the rest of the world, couldn’t have anticipated declaring another pandemic in 2020 and its massive disruptions to screening and care. Now, as the world trudges through limited COVID-19 vaccine access, outbreaks, and variants, public health experts are returning to familiar concerns while still wading through COVID-19 and seeing a worrying trend in the strains caused by the pandemic.

The WHO estimates about 71 million people living with HCV with about 400,000 people dying annually due to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma caused by the virus. Despite the WHO’s lofty 2030 goals, those numbers are growing, not decreasing. Unfortunately, that trend isn’t new.

Sarah Blach, of the CDA Foundation in Colorado, recently evaluated and updated modeling from her team’s 2017 projections under the lens of COVID-19 disruptions and the results were startling. Prior to diving into the forecasting data, it’s important to note Blach’s team found HCV screenings and treatment initiation were declining even in high income countries. Prior to COVID-19, only 5 countries out of the 110 included in the 2017 model were on track for their 2030 elimination benchmarks. The model discussion cites both the United States (with a 60% reduction in patients receiving treatment in 2019 compared to 2015) and Italy (with a 35% reduction in treatment initiation from 2018 to 2019). Blach’s modeling team provided estimations considered under a “no recovery” model, “no change scenario” relative to 2019 data (or a 1-year delay in screening and treatment uptake model), and an “escalation” model in terms of efforts to eliminate HCV – particularly among lower-middle income countries. The model found that, if the United States were to resume static screening and therapy initiation efforts at pre-pandemic levels or exceed those goals, between 10,000 and 25,000 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma would be averted from 2021-2030. Though, this model would require treating almost 250,000 people per year in order to reach the 2030 elimination goal – in context, the United States initiated treatment for just 150,000 people in 2019 (also missing the targets for the year by 10,000-20,000).

Blach’s modeling uses the United States as a frequent example because, despite being a high income country, not much in the way of incremental incident infections were expected because the United states does not largely engage in best practices related to (and some would argue “required to”) HCV eelimination (ie. fibrosis requirements related to DAA initiation, care rationing, and restrictions on treatment access for people who inject drugs. The model found under a 1-year universal delay of treatment initiation, no country would achieve HCV elimination by 2030, particularly because the year of delay in treatment initiation doesn’t stop transmission of HCV and considers many lower-middle income countries may experience additional barriers to trust and patient engagement, potentially delaying timely diagnosis for years. Limitations to the model include a universal calculation of delay and local holidays and customs may more readily adapt. The most significant limitation in the model is it does not consider the impacts of increased risk behaviors or decreased access to harm reduction programs. Blach and team use the closing moment to ask policy makers to consider the role of investigating and investing more in HCV screening and treatment efforts in order to not lose critical, fragile ground in the fight against HCV. Given a different study’s conclusions on exactly when particular states in the US might reach their elimination goals with only 3 (Connecticut, South Carolina, and Washington) making it in 2030 and several others’ efforts taking until after 2050. The same study notes, of the states with the most restrictive access to HCV care policies and lack of harm reduction infrastructure, theirs are the ones estimated to take the longest to achieve HCV elimination.

2020 did not hold all bad news for the fight against HCV though. Nature covered 3 of the most impressive study efforts in HCV, with findings presented in 2020 and 2021, which may hold some of the keys to reducing HCV-related deaths and improving other health outcome goals. Egypt’s shift from a national treatment program to a national screening program, amid the treatment program being so successful the need to identify HCV patients more readily, also modeled effective cost savings opportunities as $85 USD per patient to identify an HCV infection and $130 USD per curative course. A Scottish study found particular pharmacies were more apt to identify patients at higher risk of HCV for screening, more likely to successfully initiate treatment, more likely to maintain program of care, and more likely to achieve curative status than more traditional physicians. Lastly, a third paper found – in a limited study - prophylactic therapies could allow countries to expand organ donation access by way of making HCV positive donor material safe to provide for non-sero positive patients. As organ donations are strained, this type of progress could enhance care and outcomes among solid organ transplant recipients.

While there’s promising opportunities on the horizon, we cannot lose sight of the fact 400,000 people a year die HCV-related complications. In a year in which much the of the United States is grappling with understanding the weight of half a million deaths, the global toll of a similar number might get drowned out amid the noise of COVID. We can’t afford to leave behind these noble goals or our global partners in HCV elimination. Like with COVID (and any other infectious disease), it’s not over for any of us until it’s over for all of us. While COVID has gripped the globe and limited access to vaccines makes for a shocking headline, we’re only in the first 2 years of this disease and have made significant, even if unequal, progress. There’s a path. HCV has killed tens of millions over the last 2 decades with equally amazing tools to combat the disease. Yet and still, millions are poised to die due to inaction and lack of sustainable investments to eliminate the virus - in large part because the risks associated with HCV transmission are judged to be “moral ills”. There is no greater ill than standing idly by allowing death to rage through the most vulnerable in any society. COVID may be the mechanism for which we’re having that particular conversation on global equity in this moment and it would behoove us all to remember HCV, a treatable and curable disease, remains a threat.

340B Drug Discount Program: Here’s What Patient Advocates Need to Know

The 340B Drug Discount Program for years has had little attention, aside from a few Congressional Hearings. As we cited last month in a blog, 340B program purchases has more than quadrupled in the last decade, now exceeding Medicaid’s outpatient drug sales. This growth has disturbed the bargain made between manufacturers, providers, and lawmakers in 1992, often leaving patients out of the benefit meant to be gained by the program.

Because 340B is an exceedingly nuanced payment system design, lawmakers have been reluctant to touch the issue – fearing a need to “crack” into the legislation, lacking agreement on how to proceed, and having to balance interests that are often in conflict – preferring to leave the management of issues arising around 340B to the Health Services Resources Administration (HRSA), which then has the unfortunate duty to remind lawmakers, the agency’s statutory authority is limited, and their budget is not large enough for more meaningful oversight. As administrations change, so do the perspectives on how to ensure the intent of 340B, making sure poorer patients can afford and access outpatient medications and the care required to acquire those medications, is captured in how the programs actually operates. Leaving us with the current situation of competing interpretations and interests heading to the court system to find answers and settle disputes.

Part of this program growth is driven by hospitals as a type of “covered entity”; a 2015 analysis showed the program having grown from about 600 participating in 2005 to more than 2,100 hospitals in 2014. In fact, a 2018 Government Accountability Office report found “charity care” and uncompensated care provided by hospitals receiving 340B revenue had steadily been decreasing over the years. The Affordable Care Act has something to do with that – in extending Medicaid eligibility, the Medicaid qualified population grew and as enrollment grew, so did the amount if “disproportionate share” of Medicaid patients certain hospitals served. Ultimately, this meant more hospitals qualified for the 340B Drug Pricing Program than had prior to the ACA.